Nearly 44 000 runners registered for the 2020 Comrades Marathon and, within a day of the event in mid-June, more than 35 000 had logged their finishing times. Of those, some 4 570 didn’t set foot in SA, virtually none of them stepped anywhere near the 89 km route from Pietermaritzburg to Durban. That’s because this year’s Comrades was cancelled due to the COVID-19 lockdown and replaced by a virtual event.

Race the Comrades Legends invited runners from around the world to complete 5 km, 10 km, half-marathon, marathon and ultra-marathon runs, and to log and submit their times via their wearable device. Some ran outdoors, some ran around their house and some ran on treadmills. This year’s Comrades Marathon joined a growing list of virtual running events. The Conqueror, for example, provides attractive medals to runners who complete distances equivalent to the Inca Trail, Hadrian’s Wall, the Great Ocean Road and Route 66 – all without actually running any of those routes.

Here in SA, Discovery’s Vitality World Cup is a free event that pits countries against each other, letting you add your 30-minute morning jog to the nation’s collective effort. By mid-June, SA, Namibia, the UK and a team of small European nations were facing off in the semi-finals. These virtual events are enabled by wearable activity trackers and apps, including the likes of Strava and Fitbit. The data gathered by these apps and devices is useful at an individual level (for recording your personal bests, or for chalking up those coveted Discovery Vitality Points) and at a broader, public-health level.

Fitbit, for example, was able track trends in physical activity levels during the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. Based on data drawn from more than 30 million active users worldwide, the company recorded a 7% drop in activity in SA during the week ending 22 March 2020. In countries such as Spain (-38%) and Italy (-25%), where strict lockdowns were already in effect, the deviation was even more pronounced.

Fitbit shared its data with Scripps Research Institute and Stanford Medicine to help track the spread of COVID-19, while also launching the Fitbit Heart Study – a large-scale study into atrial fibrillation (AFib), the most common form of treated heart arrhythmia. ‘Until recently, tools for detecting AFib had a number of limitations and were only accessible if you visited a doctor,’ says study lead Steven Lubitz. ‘My hope is that advancing research on innovative and accessible technology, like Fitbit devices, will lead to more tools that help improve health outcomes and reduce the impact of AFib on a large scale.’

Similarly, researchers at the University of Washington recently unveiled a new, contactless tool to monitor people for cardiac arrest while they’re asleep, using smartphones or smart speakers such as Google Home or Amazon Alexa to detect sudden changes in breathing. ‘A lot of people have smart speakers in their homes, and these devices have amazing capabilities that we can take advantage of,’ says co-corresponding study author Shyam Gollakota.

‘We envision a contactless system that works by continuously and passively monitoring the bedroom for an agonal breathing event and alerts anyone nearby to come provide CPR. And then if there’s no response, the device can automatically call 911.’

FluSense, meanwhile, is a portable surveillance device powered by machine learning, launched by the University of Massachusetts Amherst during the early stages of the COVID outbreak. The device – which comes in a box the size of a large dictionary – is envisioned for use in hospitals, healthcare waiting rooms and larger public spaces. It tracks coughing, and crowd size in real-time, then analyses the data to monitor flu-like illnesses and influenza trends. The developers hope to use the platform to inform public health responses during flu epidemics, determining the timing for fluvaccine campaigns, potential travel restrictions and the allocation of medical supplies.

And then there’s Sanjiv Gambhir’s health tracker, which he and his team at Stanford University have been working on – and hearing jokes about – for several years. It’s a smart toilet. Or, at least, it’s a standard toilet fitted with devices that detect disease markers in stool and urine, potentially serving as early detectors for dread diseases such as colorectal or urologic cancers. ‘Our concept dates back well over 15 years,’ according to Gambhir. ‘When I’d bring it up, people would sort of laugh because it seemed like an interesting idea but also a bit odd.’

It is a bit odd. ‘Smart toilet’ doesn’t have quite the same ring to it as ‘fitness tracker’ or ‘heart-attack detector’. Yet, as Gambhir points out, a toilet offers continuous health monitoring. ‘The thing about a smart toilet is that, unlike wearables, you can’t take it off,’ he says. ‘Everyone uses the bathroom – there’s really no avoiding it – and that enhances its value as a disease-detecting device.’

What’s clear is that the e-health and medical wearables sectors are growing, fast; Reports and Data sees the global mobile health market reaching $311.98 billion by 2027.

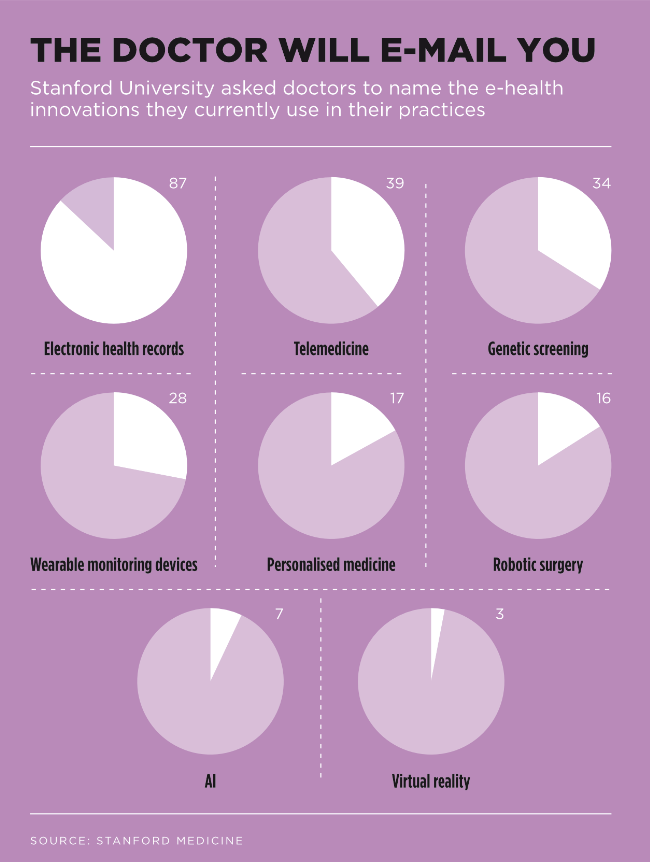

The healthcare sector appears to be on board too. A UCT study published in the March 2020 edition of the South African Medical Journal confirmed that electronic health record systems such as Discovery Health’s HealthID could ‘improve the efficiency of medical consultations by increasing access to stored health information without requiring data entry by clinicians, and thereby have the potential to indirectly improve the quality of care’. This sentiment was echoed in the US by Stanford University’s 2020 Medical Health Trends report. ‘What we found boils down to one central idea,’ writes Lloyd Minor, dean of the university’s medical school. ‘Physicians expect new technology to transform patient care in the near term, and they are actively preparing to integrate health data – and the technologies that harness it – into the clinical setting. In other words, we are witnessing the rise of the data-driven physician.’

It’s a trend that’s also improving access to private primary healthcare in SA. National HealthCare Group, a company that offers access to private primary healthcare through its 10 000-strong provider network to the lower-income segment of the SA market, recently launched its MediClub Connect app. The online, interactive service provides members with access to doctors and nurses via WhatsApp, physical consultations with doctors on referral, prescribed medication and other key services, for a monthly fee of no more than R95 per employee.

National HealthCare Group CEO Patrick Lubbe says the solution (which was launched in May, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic) fulfils a considerable need for more accessible healthcare and empowers individuals to monitor their health closely, adding that the offering ‘differentiates itself through delivering healthcare to the palm of the hand using a mobile phone and a series of WhatsApp prompts to pinpoint potential healthcare issues’.

Not only will it stand businesses in good stead by reducing absenteeism and strengthening the bottom line, he says, but it also builds morale, solidarity, loyalty and, ultimately, good labour relations.

‘With only a fraction of South Africans employed in the formal and informal sector having access to quality, affordable private healthcare services, the implementation of NHI will come as a series of major shocks to the entire healthcare system,’ says Lubbe. ‘We must therefore be proactive in developing viable alternative streams of health support, which will go some way towards eliminating the inequity that exists in healthcare immediately, while ensuring that the basic healthcare needs of employees are met.’

Physicians (including those in training) are increasingly seeking out education in data-science disciplines, according to Minor – and they’re open to using emerging sources of patient data as part of routine care. These developments, he adds, ‘have significant potential to advance patient care and empower tomorrow’s healthcare providers to predict, prevent and cure disease – precisely’. That’s a big promise, and one that comes with its own caveats. For instance, the study warns that few of the doctors surveyed feel ‘very prepared’ to implement emerging technologies in clinical practice, while a study review by Columbia University, published in the Lancet in May 2020, called on the global health community to establish guidelines for the development and deployment of these new technologies.

‘Especially during the COVID-19 emergency, we cannot ignore what we know about the importance of human-centred design and gender bias of algorithms,’ says Nina Schwalbe, public health expert and faculty member of Columbia University.

In the meantime, a wealth of life-saving data continues to be gathered by ordinary people who’re tracking their runs and checking their heart rates on their wearable devices.