When Rhodes Business School (RBS) introduced management education that focused on the ‘4Es’ of economy, ethics, ecology and equity, people were taken aback. ‘Initially we were criticised for taking the sustainability approach, but in the wake of the 2008/09 global economic crisis, everything changed, and business schools worldwide started recognising its value,’ according to Gavin Staude, RBS founding director, who retired in 2010 after a decade of encouraging sustainability in SA business education.

He explains in an anniversary publication that the school’s philosophy of ‘Leadership for Sustainability’ grew at a time when the UN was very keen on business schools promoting this approach, as sustainability was increasingly becoming an issue at a global level.

‘Right from the start we recognised the value of the “people, planet, profit” approach or the need to balance financial objectives with social and environmental sustainability,’ writes Staude.

Other business schools have followed suit. In SA, recent corporate governance failures have brought ethics – which is the ‘G’ in ESG (environmental, social, governance) issues – to the forefront of business education.

The country has learnt the hard way just how paramount good governance is, with the economy still recovering from the allegedly corrupt previous administration, accounting scandals and collapse of state-owned entities. And, unsurprisingly, students, employers and business-school accreditation bodies are showing more interest than ever in the inclusion of ethics and sustainability in business education.

‘Business schools have a crucial role to play in developing the conscious corporate leaders of the future, to ensure we embed integrated thinking into the way we run our businesses and create value in a sustainable manner,’ says Mervyn King, the former supreme court judge who gave the name to the trailblazing King Report on Corporate Governance.

Earlier this year, he was appointed honorary professor at Wits Business School (WBS), where he will be involved in teaching and supervising students as well as organising colloquia and other public events on corporate governance. In 2019, King established the Good Governance Academy to share information for the greater public good. The aim is to become a catalyst between local and global tertiary educators in business science and hold at least two colloquia on critical governance issues per year. The most recent colloquium, held at Regenesys Business School, discussed effective corporate leadership, while the upcoming one at WBS will investigate ‘integrated thinking’.

This conscious effort towards improved corporate governance reflects a global trend in which, according to the UK-based Financial Times, responsible business education is taking hold ‘even at prestigious schools that traditionally focused on mainstream skills’. The newspaper notes that an increasing number of international business schools have launched focused sustainability modules and bespoke MBA qualifications, with specialisations including MBAs in sustainable solutions; the purpose economy; and sustainability leadership.

Closer to home, Tshwane University of Technology Business School recently rebranded itself as Tshwane School of Business and Society (TSB) – a name adjustment that demonstrates its new vision as a facilitator for social and economic change.

The school is only the fourth tertiary institution worldwide (and Africa’s first) to have combined ‘business and society’ in its title, says TSB director Kobus Jonker. The others are in Tilburg (Netherlands), Glasgow (Scotland) and Milan (Italy), where TSB has partnered with the Catholic University’s ALTIS Graduate School of Business and Society to introduce an international certificate in impact entrepreneurship.

‘The programme was developed specifically for Africa and has already been launched successfully in eight other African nations,’ says Jonker, who took over the helm of TSB in January 2019 to raise the school’s profile.

‘Our slogan is “Lead for Impact”,’ he says. ‘We believe that business schools shouldn’t focus exclusively on servicing the corporate sector but also on developing entrepreneurs, particularly in townships. We want to help these entrepreneurs to take their businesses to the next level and employ more people in order to make an impact on society.’

Meanwhile, Milpark Business School (MBS) has kept its name after joining Stadio Multiversity but updated its slogan to show commitment to responsible leadership education. The school explains the motivation behind the new slogan – ‘Tomorrow is Beautiful: Developing ethical leaders for the common good’ – on its website.

‘In demonstrably making MBS’ philosophy manifest, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will serve to inform the way we think, reason and act in relation to teaching, research and engagement with industry.’

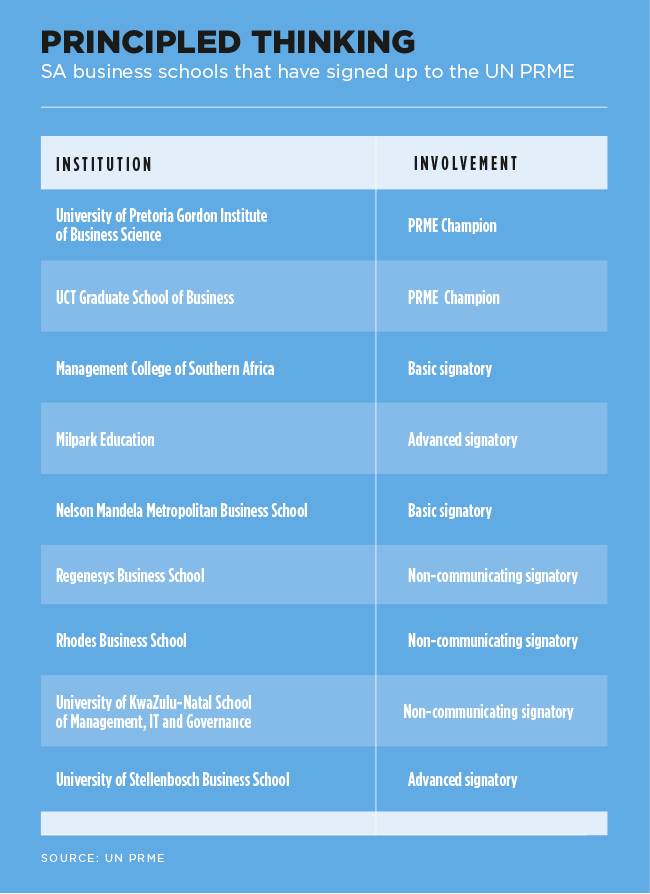

The private education provider is part of the UN’s Principles for Responsible Management Education (PRME) initiative, which – based on six principles – guides business schools and raises global awareness of the importance of responsible management in education institutions.

The signatories agree to incorporate the PRME vision in their curriculum and research while also committing to sharing regular progress reports online. By March 2020, nine SA business schools had signed the initiative, with two actively involved as ‘PRME Champions’, namely the University of Pretoria’s Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) and UCT’s Graduate School of Business (GSB).

Worldwide, the small PRME Champion groups focus on developing and sharing best practices in thought and action leadership on the SDGs, according to GIBS faculty member Jill Bogie. ‘[It’s] now in its fourth two-year cycle, [and] 36 schools were invited to participate in the current cycle and tasked with building PRME practices in member schools to transform business and management education by embedding the SDGs into teaching and research,’ she says.

‘This follows from previous work that is still ongoing on developing an SDG blueprint for business schools, an online resource to be launched later this year.’

This may sound abstract, but the initiative has already achieved tangible results. The PRME involvement has allowed GIBS to focus very directly on further embedding the SDGs into the work of the school, says Bogie. ‘While there were many existing initiatives around sustainability, responsible leadership, ethics and governance, there is now more attention and energy given to the SDGs, with greater clarity of intention and direction.’

For example, new core courses in the MBA and other Masters programmes have introduced methods and tools for understanding global challenges, considering new business models, designing innovative strategies and how the SDGs can be incorporated into strategic decision-making. Bogie adds that as a result, ‘more and more students are choosing to include SDG-related topics in their final research projects’.

In November 2019, the GIBS Ethics and Governance Think Tank announced the first results of its Ethics Barometer for South African business. The benchmarking tool was developed in partnership with Business Leadership South Africa and Harvard Business School, and it involved surveying 15 leading companies, including the JSE, from diverse sectors. It’s built on the premise that if businesses can measure ethical behaviour, they can manage it more effectively and move it to the centre of organisational decision-making.

Away from the business hub of Gauteng, RBS director Owen Skae says students are drawn to Makhanda, Eastern Cape, because of the school’s focus on sustainable leadership. ‘But even those who are passionate about sustainability, confirm that they learn from the integrated way in which we teach these principles,’ he says. ‘In looking at the 4E model, we consider how management accounting or people management – or any other subject for that matter – can ensure that business does the necessary transformation for an inclusive economy that maintains ecological balance, ideally doing no harm, premised on an ethical foundation that it is implemented in an equitable fashion.’

Referring to a recent MBA module on management accounting, Skae says that ‘some students confirmed, as they put it, that we don’t often pay enough attention to the “critters” or “creepy-crawlies” and may not have thought twice before the teaching block about spraying the insects that irritate us in our home. Applying the lens of “extinction accounting” and “stranded assets” to a discipline that we thought was only about numbers has opened our minds to why we need to urgently change the way we do business’.

That’s exactly how business schools can contribute to developing a new generation of responsible, more ethical corporate leaders: by not only teaching them conventional business science and skills, but by also sharpening their awareness of ESG issues and encouraging integrated thinking.

These days, few would dare to criticise a business school for taking a sustainability approach. Quite the opposite, as such business education has its role to play in embedding ethical behaviour and future-proofing SA’s business and society.