Supposing water wasn’t so cheap for users, SA might not be in the midst of a water crisis right now. For many businesses, water has not featured on the balance sheet in the past and therefore has not been considered worthwhile enough to take into account. ‘The subsidisation of water prices has also undermined the maintenance of water infrastructure, as well as the protection of water resources,’ says Willem de Lange, environmental and resource economist at the CSIR.

‘Financial incentives are a most powerful lever for behavioural change, because there’s not much incentive to look after a resource when it’s free or nearly free.’ There are various financial levers, such as block tariff pricing, permits, rebates and fines – although he cautions that adjusting water prices is not a simple matter in a country with big socio-economic disparities.

In hindsight, a higher price tag on water could have nudged users – that’s households as well as businesses, factories, mines, energy producers and farmers – to change their consumption patterns much sooner, possibly averting or at least delaying the current water crisis. Tragically, the underpricing of water coupled with SA’s relatively well-developed water management and supply infrastructure has given water users a false sense of water security and lack of appreciation for this strategic resource, according to De Lange.

‘Companies frequently assume that because the cost of water is so insignificant to their bottom line, it’s “not material”,’ says Michael Rea, managing partner at Johannesburg-based Integrated Reporting and Assurance Services (IRAS). ‘There continues to be a trend among companies to assume that “materiality” is based solely on “volume used”, where many companies continue to state that because they are not in the mining or agricultural sectors – and thus don’t consume as much water – water isn’t a major concern for them.’

IRAS compiles an annual analysis of JSE-listed companies’ reporting on environmental, social and governance issues, and found that just 108 of the 311 companies assessed had given details on water consumption in their 2016 integrated annual reviews. The problem, says Rea, is that ‘materiality should never be exclusively based on cost and/or consumption, but rather on whether the mismanagement of the resource could have a significant impact on the future sustainability of the business within the context in which they operate’. However, it’s not only the sustainability of businesses that’s at stake.

Water is a shared resource that affects absolutely everybody and it’s key to growth. All economic activity requires water, as does

all life on Earth. ‘Water is one of the primary inputs in all sectors of an economy and is, therefore, a crucial resource with huge political significance,’ says De Lange.

The WEF 2017 Global Risk Report – now in its 12th year – ranks water crises third in the top five global risks in terms of impact. It also ranks the closely connected environmental risks of extreme weather events (second) and major natural disasters (fourth). Locally, a comparable report by the Institute of Risk Management South Africa reveals water crisis and droughts as number two and four respectively in the country level risks category. However, neither event made it into the top 10 SA industry level risks, which don’t include any environmental risks and instead list strike action, exchange rate fluctuation and lack of innovation as the top three risks.

Meanwhile, the water crisis has already directly hampered socio-economic development, according to the 2017 WWF report on scenarios for the future of water in SA. The drought has widened the trade deficit due to losses in maize exports, caused agricultural job losses and accelerated consumer inflation because of higher food prices. This shaved 0.2 percentage points from SA’s economic growth in 2015, notes the report.

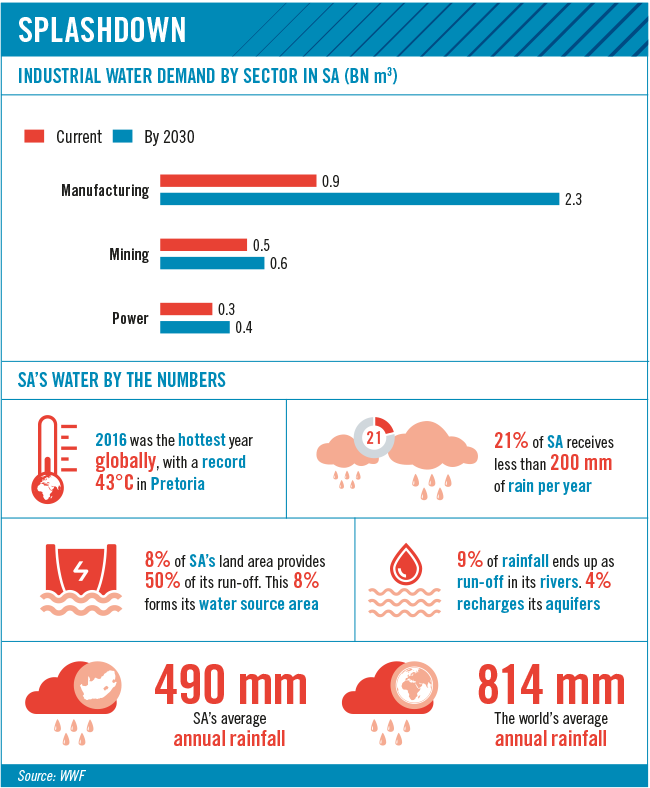

It goes on to explain that water demand in SA has increased steeply, driven by agriculture (63%) and the municipal (26%) and industrial (11%) sectors. Demand will likely continue to grow at around 1% annually, from 15 billion m3 in 2016 to approximately 18 billion m3 in 2030 – by which time water demand is expected to exceed supply by 17%.

The WWF report further highlights that the major water user within the industrial sector is manufacturing (currently accounting for 53%), which includes applications such as the proces-sing of minerals and crops; textile and chemical refinement; and component and auto supplies. Other big users are mining (27% of the industrial water demand) and power generation (20%).

‘The big strategic challenge is that the planning and implementation of the large water resource projects that underpin South Africa’s water security is breaking down,’ says Mike Muller, water expert and visiting adjunct professor at Wits University’s School of Governance. ‘We don’t need new plans, just implementation of what’s on the table,’ he says, referring to the 2004 National Water Resource Strategy and 2012 NDP.

‘There are many other problems in South Africa’s water sector – most of which will have to be addressed by improving governance at local and national level, to ensure that the right technical capacities are in place, and systems are properly operated and maintained.’

The City of Cape Town, one of Africa’s most proactive metro municipalities in terms of water management, will invest more than R2 billion in new desalination, ground water extraction and water reuse plants. An additional R1.3 billion will be spent on operational costs over the next two financial years. By mid-August, the city’s water resilience task team had received in excess of 100 private sector submissions offering desalination (including container solutions, barges and ships), and water reuse technology at various scales; aquifer and borehole options; and engineering and infrastructure options.

In September, the city imposed Level 5 water restrictions on businesses and households to further reduce consumption. Fines will be issued to those who use more than their allocated volume of municipal drinking water – or waste it on non-essential purposes such as watering golf courses, lawns or gardens, washing cars, topping up pools or hosing down hard surfaces or paved areas.

‘We are appealing to businesses to promote water-saving habits among staff and facility managers. Commercial water users can reduce their consumption by installing water-efficient plumbing fittings and water-saving devices,’ Cape Town’s executive mayor Patricia de Lille said in a media statement. ‘This measure is not intended to negatively impact business operations but to ensure sustainability of the commercial sector by bringing about the necessary behavioural changes and mindset to adapt to the new normal,’ said De Lille.

However, some business sectors such as the hospitality and service industry showed an immediate impact. The Radisson Blu Hotel Waterfront closed its swimming pool, and Virgin Active switched off steam rooms and saunas in their gyms, while Tsogo Sun has banned hotel guests in the Cape from bathing to reduce water usage.

A few months previously, Minister of Water and Sanitation Nomvula Mokonyane and other key role-players met at the high-level Western Cape Water Security Indaba to discuss solutions. ‘This water crisis – similar to the energy crisis we faced in 2008 – is an opportunity for South Africa to emerge as the fastest-growing water economy in the world,’ said Western Cape premier Helen Zille.

Alex McNamara, climate and water programme manager at the National Business Initiative (NBI), underlines that all companies in SA face water risks and that these were here to stay. ‘Financial services are exposed through their portfolios, large water users are directly affected and others indirectly through their supply chain,’ he says. ‘Water requires looking beyond your own operations. You can have your own water storage tanks but you will still rely, to some extent, on public sector water services.’

The NBI has developed a water programme with the objectives of raising corporate awareness of key water issues; engaging with members on best practice tools and approaches; supporting company-related water disclosure and risk management; and facilitating partnerships and project implementation in the water space.

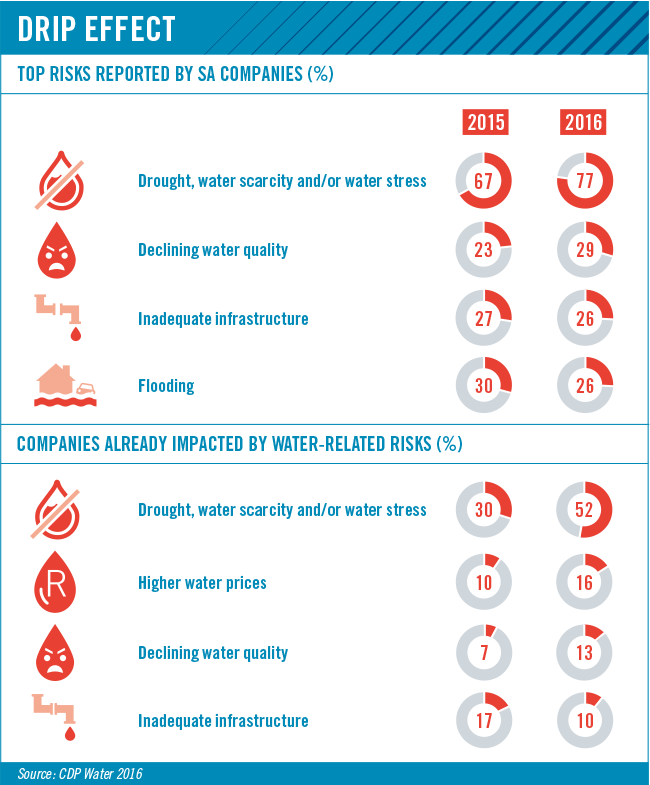

For the past seven years, the NBI has run CDP Water (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) in SA, which requests water-related information on behalf of 643 investors with more than $67 trillion in assets under management. About 40 companies listed on the FTSE/JSE Africa All Share Index (and operating in sectors greatly impacted by water resources) report globally via CDP on their water use, risks, opportunities and management practices.

Overall, CDP Water performance scores have improved across the board, with four SA companies out of a global total of 24 reaching the water ‘A-list’ (Anglo American Platinum, Harmony Gold, Kumba Iron Ore and Royal Bafokeng Platinum). ‘We expect the A-list to increase this year,’ says McNamara. ‘SA’s leading pack of companies is doing well in terms of water management across a spread of sectors including food and beverages, retail and obviously mining – a key industry that in some

areas provides communities and municipalities with potable water.’

He points out further water-related achievements such as the ‘We Mean Business’ commitment to improve water security that was signed by four companies (Royal Bafokeng Platinum, Tiger Brands, Tongaat Hulett and Woolworths). And then there are some major corporate water stewardship projects, notably by South African Breweries, Sanlam, Sasol and Woolworths, along with smaller initiatives by companies such as Distell.

McNamara advises businesses to ensure their internal water governance is in order and that they understand their water risk (in its overall context, including the supply chain). Other crucial points are engagement with suppliers, local authorities and policy-makers while setting more ambitious water targets.

The NBI encourages businesses to participate in initiatives such as CPD Water, the voluntary Alliance for Water Stewardship, the CEO Water Mandate, the global commitment to ‘Improve Water Security’ by the We Mean Business coalition, and the National Cleaner Production Centre’s Industrial Water Efficiency Project.

‘The enthusiastic adoption and practice of the six steps recommended by the Alliance for Water Stewardship will make a dramatic, positive impact on South Africa’s economy and remove significant risk,’ says Kevin Barlow-Jones, stockbroker in control at Sinayo Securities, which organises a water stewardship summit. These steps include commit (to being a responsible water steward); gather and process (data to understand water risks, impacts and opportunities); develop (a water stewardship plan); implement (the plan and improve impacts); evaluate (performance); and communicate and disclose (results and efforts).

‘Business has a role to play in creating awareness and establishing a culture of water saving in South Africa,’ says Grant Neser, MD of JoJo Tanks. He says behaviour in a workplace can influence the behaviour at home.

‘Business should be proactive in anticipating water prices being increased to reflect underlying costs. It’s also likely that government will subsidise basic domestic consumption by hiking rates for industries and commercial users, as well as high-usage households. Everyone should be giving attention to all water-saving options such as rainwater harvesting, separation of potable and non-potable applications, efficient water usage and recycling and reuse of water.’

Whatever the hydrological future of SA, companies need to prepare themselves for continued water scarcity, or the ‘new normal’. The risk of demand overtaking supply is real, although De Lange believes we won’t physically run out of water.

‘The crux of the problem is distribution and cost,’ he says. It’s increasingly expensive to clean, filter, chlorinate and pressurise drinking-quality water and pump it to where it’s needed. ‘We won’t run out of water but it could become prohibitively expensive,’ says De Lange.

This means that industrial water reuse, recycling and innovative water technologies are set to become a way of life for SA businesses.