You see it in new bank branches. You see it in new bank buildings. You see it in new banking services.

From Standard Bank’s super-green, glass-fronted corporate building in Rosebank to its super-cool Playroom innovation lab a few blocks away. From FNB’s hip new branch in the Mall of Africa in Midrand to the digital platform that underpins the FNB Connect network service.

Banks are fast waking up to the fact that they face a rapidly shifting customer landscape. And that, if they themselves don’t participate in this shift or even lead it, they will be shoved out of the way.

‘Disruptive forces are coming into financial services, with massive changes happening in the payment space, the arrival of Bitcoin and blockchain, cashless and mobile banking,’ says Yolande Steyn, who recently joined Vodacom as managing executive for digital and customer experience.

She had previously headed up a division at FNB called FNB Innovators, and the move to Vodacom seems to tie in with a long-standing flirtation with banking by mobile operators. Arch-rivals MTN recently appointed one-time Nedbank retail boss Rob Shuter as its group CEO, fresh from his role as head of Vodafone in Europe.

Mobile operators have, so far, failed to disrupt financial services, despite conventional wisdom that their massive customer bases and money flows made them the ideal catalysts for a fintech revolution.

Instead, it is the banks themselves that are leading the disruption, even intruding on the mobile operators’ spaces.

FNB’s hugely successful eWallet service proved the viability of mobile money at a time when M-Pesa failed to make a dent in the market. No fewer than 6.7 million people had received money into their eWallets by the middle of last year.

Mobile-phone banking, another area pioneered by FNB a decade ago, still has 3.5 million customers using USSD menus on their phones. FNB has had an Innovators programme since 2004, but serving as an internal scheme, rewarding implementation of ideas.

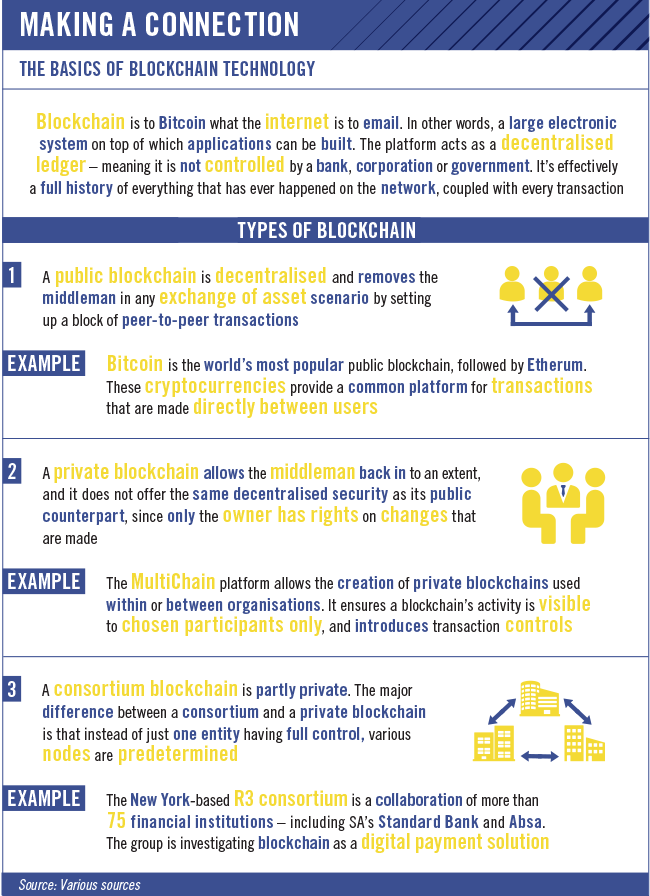

Right now, an innovation so powerful it could change the course of global financial and identification systems is about to explode. It’s called blockchain, and it is premised on a simple idea that goes back almost 500 years to the invention of double-entry bookkeeping.

Blockchain is a digital version of the ledger, but one in which all transactions are recorded in sequence, and shareable via any computer network.

The best known example is Bitcoin, a crypto-currency used to shop at a few hundred thousand outlets around the world. It exists purely as encrypted code, and is independent of any central bank. The result is that trust and security of the system resides in the system itself. No wonder many banks and other institutions are dancing around it rather than embracing it. The technology underlying Bitcoin, however, is a different matter.

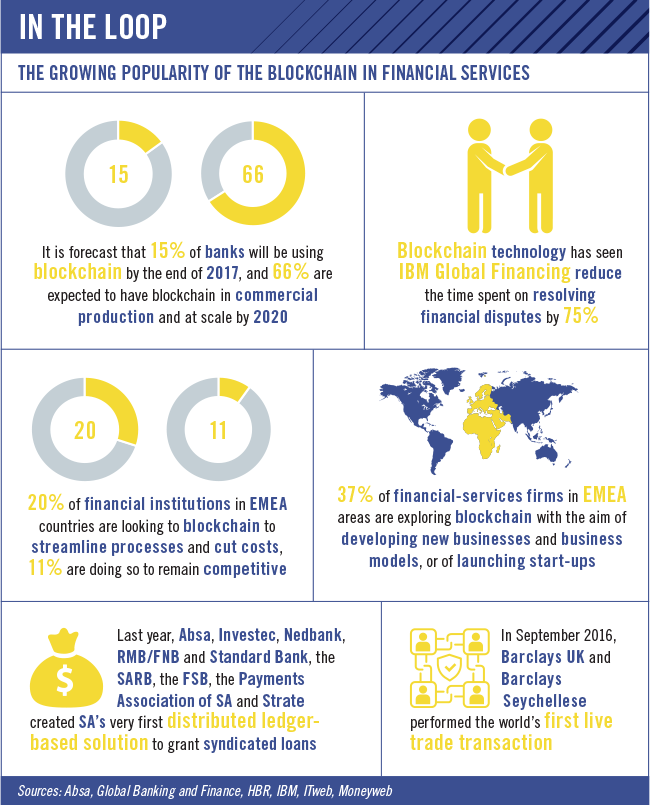

Major banks worldwide are exploring blockchain – and SA is no exception. The recently established South African Financial Blockchain Consortium (SAFBC) comprises more than 20 industry players, including the South African Reserve Bank (SARB) and the Financial Services Board (FSB) as observers. In October last year, Absa, Investec, Nedbank, Standard Bank and RMB/FNB together with the SARB, FSB and Strate successfully swapped an asset via the blockchain network Ethereum.

Blockchain technology ‘promises greater efficiency and reduced costs and could open up the ecosystem to new players, ultimately benefiting consumers’, says Farzam Ehsani, SAFBC chairman and blockchain lead at RMB, as reported by Moneyweb in early July. ‘We’ll definitely consider other platforms as the entire blockchain industry is nascent and new platforms are emerging’, he says, adding that ‘the only way to unleash the potential of this tremendous technology is through collaboration’.

Financial institutions must become participants in digital disruption rather than its victim. They can also maintain the role of the trusted third party in transactions. ‘There will still be a role for a number of parties in future, but it will be different,’ says Tanya Knowles, executive director of Fractal Solutions, the innovations division of Strate that maintains a database of who owns what shares on the JSE. ‘In a regulated financial system, as soon as you develop a private or commissioned blockchain, there still is a role to co-ordinate that ecosystem – from rights to the system and who regulates it, to the transparency of what people can see and can’t.’

Blockchain is tailor-made for share transactions. As a result, Strate is a participant in the SA blockchain working group. However, the potential impact goes beyond financial systems. It can, for example, address the trillion-rand annual global loss from diamond-dealing fraud. ‘People want to apply the technology to other industries,’ says Knowles. ‘The most recognised example is a distributed ledger for Know Your Customer compliance like the Financial Intelligence Centre Act.’

The act requires all financial services operators to verify the identity of customers every time they open new accounts. ‘Why authorise yourself at every single venue? If you put identity on blockchain and a network of trusted parties, you only have to FICA once, as the database won’t be held by an authority that can be corrupted.

‘Strate had the idea for 10 years, of creating a central database of FICA info. But it can end up like Home Affairs, where the system can fall over or have insiders going into the back end, so it leads to traditional problems of relying on one party. You’ve got to look at three or four different trusted sources.’

If blockchain is such an obvious solution, why is it taking so long to emerge from below the surface of its possibilities? The answer, ironically, is that its initial uses are all ‘so what’.

‘People say blockchain is a solution looking for a problem,’ says Knowles. ‘The issue is that it is being applied to systems that are not broken, like banking. But the big opportunities are lurking where systems are not working.’

The entire payments space is a case in point. The point of sale is at once the most powerful interface for tracking consumer behaviour and the most fragmented in terms of both connectivity and trackability. Mobile payment solutions only solve half the problem, as most point-of-sale systems are not ready for them.

The cutting-edge mobile payment services announced in recent years, such as Apple Pay and Samsung Pay, are dependent on adoption by merchants more than by consumers. That, in turn, means that the mobile payments revolution has to be preceded by a revolution in what the banks call ‘acquiring’ – signing merchants on to their credit card and payment platforms. The bank is then allowed to accept the card payments taken by the merchant at the point of sale.

Acquiring and acceptance make for a particularly unsexy business, as they depend more on sales technique than on cool technology and apps. As a result, the typical consumer only adopts a mobile payment solution when confronted with it at a pay point or restaurant table.

Apps such as SnapScan and Zapper require customers to use their smartphones to scan a mobile barcode called a QR code. The apps compete with hardware terminals such as Absa’s Payment Pebble, Nedbank’s PocketPOS, and the independent iKhokha – isiZulu for ‘to pay’ – which all connect to a smartphone or tablet managed by the merchant. And there’s the rub: if it’s merchant-driven, it’s also acquirer-driven, meaning that every merchant has to convince a bank to ‘acquire’ it.

Many online retailers get round this limitation by signing up to ‘supermerchants’, third-party payment processors who are allowed by the banks to sign up as single large merchants on behalf of numerous small businesses. That option has been late in arriving in mobile payments, although both Absa and Standard Bank offered a semblance of this service through lower barriers to entry for the likes of one-person businesses.

Yoco, formed in 2012, spent two years developing both its technology and an argument for a bank to give it supermerchant status. It was finally given the go-ahead by Mercantile Bank in 2014, and now offers a low-cost terminal that plugs into a smartphone and allows every member of staff to process payments on the fly. All payment information is processed in the cloud, and an online platform allows merchants to analyse product, staff and store performance.

Yoco sets itself apart from most by going beyond payment processing, offering a platform for business functionality including item management, staff management and sales analysis. That means it is not merely a payment processor but a payment ecosystem. In that sense, it represents the next phase in the evolution of mobile payments.

The same can be said of a start-up called Zapper, which is often seen as competition to the Standard Bank-owned Snapscan. ‘We facilitate payments with the hope of offering value-added services,’ says founder David de Villiers. ‘We offer analytics and insights and we are their big data platform and marketing platform. That means we enable a merchant to be a modern business.’

The breakthrough for Zapper came when it persuaded restaurants to allow it to integrate QR codes into restaurant bills – a first in SA. Customers use their phones to scan the codes, and pay the bill without removing a credit card.

An equally significant breakthrough came when Zapper broke into two of the world’s most challenging retail markets, the US and the UK. In the former, it has cracked the fast-service restaurant sector, signing up 60 outlets of the Dairy Queen franchise in Texas, with another 250 to follow in the American south.

‘In the UK, we have targeted retail convenience, because our platform is excellent for enticing people to come to particular stores,’ says De Villiers. ‘For example, it allows for condition-based vouchers, so we can enable a reward or incentive based on what’s in basket, not just what you’re spending, like giving one free Corona for every two you buy.’

Digital loyalty cards and a partnership with Alipay – the payment platform created by Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba – are next on the agenda for Zapper. De Villiers believes that, in the payments space, continual innovation is not negotiable. ‘It’s a very fragmented and highly competitive environment, and the only way to keep merchants and consumers is continually to innovate and continually to add value.’

So what are the main challenges facing the fintech industry in Africa? According to Schalk Nolte, CEO of Stellenbosch-based authentication and mobile security company Entersekt, it’s ‘our own lack of confidence’, particularly on the business side. ‘We have the ideas, but we fear someone in Silicon Valley or London or Amsterdam is minutes away from having the same thought or improving on it – that they’re already doing it – and that they’re right where it’s happening, with instant access to funding and hordes of brilliant, experienced professionals. Of course, that’s reality for most of us – we bootstrap longer, scale slower, avoid big risks while, sometimes, fending off the copycats.’

The fintech revolution may be heavily hyped, says De Villiers, but the sector is exploding for a reason.

‘Inefficiency will always breed the opportunities for disruptors and innovation. Financial services across the world had significant inefficiencies and still do, therefore it will be a space for innovators to disrupt. A lot of people are jumping in and you’ll see a lot of successes and failures. Is there an opportunity to do financial services better than in the last 30 years? Absolutely. There are many, many opportunities.’