While there has been a frenzy of merger and acquisition activity in the global chemicals industry, JSE-listed SA firms have yet to be caught up in the mania. Although to date no big changes are expected in the local competitive landscape, this does not mean the buyouts will go unnoticed. For example, China Chemicals has bought Syngenta, a supplier of pesticides to SA farmers.

Even more striking is the debt-fuelled $62 billion Bayer bid for the Monsanto group. This offer price is easily way ahead of the R290 billion combined market cap of the big four in SA: Sasol, AECI, Omnia and Afrox.

Speculation is rife that – if successful – Bayer will pull Monsanto as it expands its offering to include rebranded genetically modified seeds alongside its core pesticides business.

Shrinking revenue in the US chemicals sector in 2015 and borrowing costs close to historic lows have proved a catalyst for these ambitious deals that also saw Dow Chemicals buy DuPont.

Locally listed firms, which do not have access to such cheap finance and do not face the same unrelenting performance pressure from activist investors, may have greater freedom to ‘shape their own destinies’. In addition, some mining chemicals firms may be too specialised to be targets. This lack of ‘life-changing’ deals among locally listed chemicals firms does not mean they have been idle in the stagnant industrial economy. They too have bought and sold small businesses to increase profits and diversify. The difference is that they have not been buying each other.

Investment in new manufacturing machinery has also not stopped – it has just changed. Rather than investing to expand capacity, firms have been buying new technology to decrease production costs, including labour. Most analysts believe the global hard commodities market has hit rock bottom. Still, there is little agreement on when a sustained improvement will start.

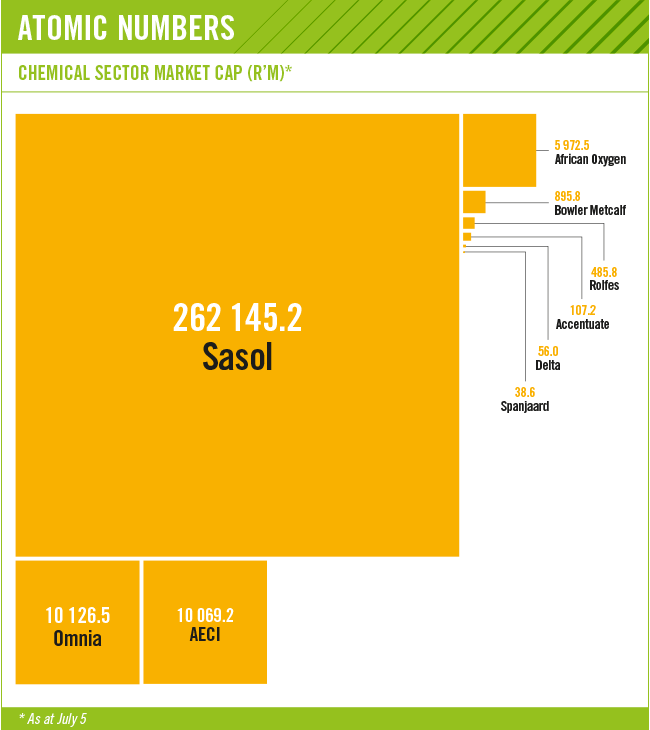

Energy and chemicals group Sasol – with a market cap of around R260 billion – is comfortably the biggest company in the chemicals sector, despite taking a company-specific knock that goes beyond the pain in the oil industry.

Although it has interests in energy, Sasol earns nearly half of its money from chemicals. The group – which has been an important rand hedge option for SA investors – has a long-term aim of boosting US dollar chemical earnings. The main pillar of this strategy is the building of an $8.1 billion chemical plant at Lake Charles, Louisiana, US. However, with hindsight, the timing of the construction proved to be poor. This, after the base chemicals price unexpectedly fell 23% in the half-year to December 2015 (compared to the same period in the previous year). Still until June this year, Sasol had weathered the oversupply storm, slashing costs ahead of target.

However, on 6 June, Sasol dropped a bombshell that had little to do with the vagaries of the oil and related chemicals market. According to the company, the cost of the Louisiana ethane cracker would come in at $11 billion, a whopping $2 billion over budget. The market was stunned and the share price fell in excess of 10%, the biggest one-day loss in more than 17 years.

A much smaller SA project sees Sasol continue to invest in its growing Mozambican natural gas business. Included in this is Sasol’s co-investment of $210 million to build another natural gas pipeline from Mozambique to SA. Aside from the business case of this project expansion, it has the potential to benefit energy-starved Southern Africa.

Investor service Seeking Alpha argues that for those that have invested in Sasol since the Lake Charles knock, there may be a silver lining. The company adds that Sasol’s lower share price may now make an investment in the group a value proposition, compared to global peers in the oil business. ‘Fundamentally, Sasol is a well-entrenched South African company managed to conservative financial policies and operating targets.’

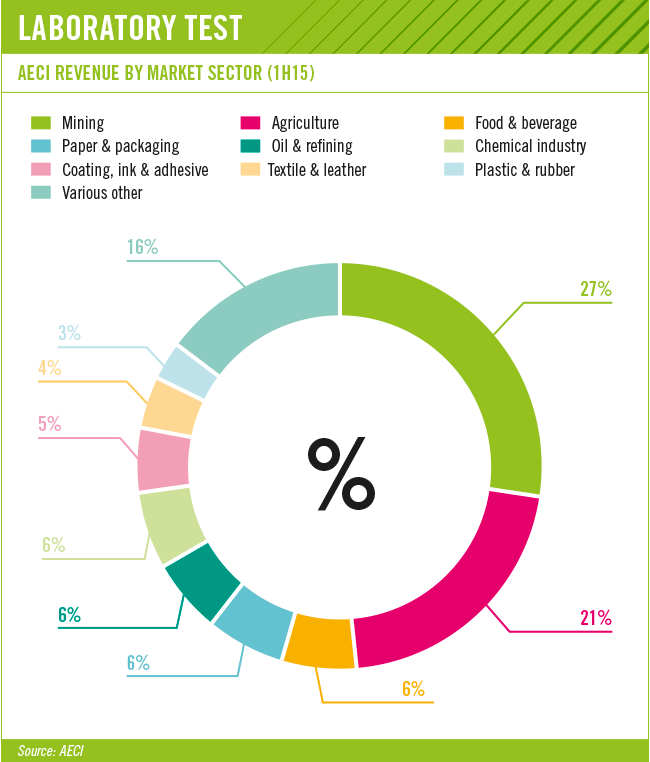

AECI, comfortably the biggest pure chemicals sector player with a market cap of about R10 billion, has significant exposure to the African resources sector. The firm says that in the year to December 2015, they have managed to increase volume sales of explosives to mines, but this came at a margin sacrifice. These higher volumes were achieved as activity levels in the platinum industry were restored after the 2014 strikes, albeit still way below ‘typical’ levels.

Still, the performance was mixed, and did not yet indicate a strong recovery in resources. According to AECI, trading in the coal-mining sector was poor. While SA’s manufacturing production is yet to recover to 2008 levels, AECI reported its biggest profits from specialty chemicals, which include sales to factories and the agriculture sector.

In what appeared at first glance a shift away from its core business, AECI acquired Southern Canned Products (SCP), a manufacturer of juice ingredients. However, the chemical maker argues this was done in order to give it access to SCP’s beverage additives business, noting that performance ‘exceeded expectations’. These mixed results contributed to the AECI group’s annual profit attributable to shareholders, declining 8% to R1.01 billion.

Earlier this year gases supplier Afrox – majority owned by the German Linde group – confirmed the countrywide struggle in SA factories when it reported results for financial year 2015. Afrox noted that lower production by customers in the manufacturing sector – including steel – hurt compressed gas sales but bulk liquid gas sales performed better.

However, just because chemicals customers in the manufacturing sector are not experiencing revenue growth, it doesn’t necessarily follow that there won’t be profit growth at factories making chemicals. This was pointed out by research house Intellidex in a report published in Moneyweb Investor in May on US-style ‘lean manufacturing’ taking hold in SA – now also a relatively expensive exercise for factories.

According to Intellidex: ‘Overall, the trend has seen large energy-intensive manufacturing such as smelting and steel production decline – while food, plastics, chemicals and beverages have done comparatively better. Those that provide reasonable prospects for investors have focused on improved technology and the sectors that are offering better growth prospects.’

Following on from this, capital expenditure aimed at reducing costs at a chemical factory can come at a fraction of the outlay needed to modernise an old steel plant.

Afrox appears to have already taken some of this ‘trim the fat’ approach to heart. Annual profits were up as the company exited unprofitable businesses and cut costs through outsourcing. This enabled Afrox to pay a dividend again and slash net debt by R335 million to only R148 million.

Omnia – one of the market leaders in the fertiliser component of agricultural chemicals – stresses that the global glut in raw materials also extends to agricultural commodities such as maize and wheat, despite recent poor harvests in SA.

Indeed rainfall over the 2015/16 summer season was the lowest on record. In the midst of this, the rand plummeted after the firing of then Finance Minster Nhlanhla Nene. These factors combined to drive the increase in the rand price of maize, all at a time when there is a global surplus. ‘The global economy is facing headwinds on several fronts, with most commodities – whether they be metals, oil or grains – in complete oversupply,’ says Omnia.

The idea of excess food may be difficult to stomach in SA, given the devastating drought. Still, were it not for the substantially weaker rand, this country would be in a position to import staples cheaply, with prices close to all-time lows.

While over the 2015/16 summer both maize plantings and the harvest declined, at the time of going to print, Omnia had yet to update its market fertiliser sales since the first-half to September 2015. However, investors have drawn their own conclusions about agriculture and mining sales, and the Omnia share price has fallen about 40% over the 18 months to April, according to Intellidex.

As bad as the El Niño-related drought was, the US Climate Prediction Centre forecasts there is a better than even chance it will be followed by a rainy La Niña over the summer, potentially reinvigorating Omnia fertiliser sales.

Still, it hasn’t exclusively been the bigger firms that have proved to be durable in the struggling economy. Plastic packaging maker Bowler Metcalfe has continued to be a steady performer in the half-year to December 2015, benefiting from a restructuring in March 2015.

The company sold Quality Beverages – which included the mass market Jive brand – to Shoreline in return for a 43% stake in a new company called SoftBev. The rationale for Bowler’s ‘operational disposal’ of the drinks business was to concentrate on its customised packaging division. The deal has already paid off with a 45% rise in earnings growth from continuing operations.

Rolfes Holdings is a growing chemicals group that has also increased its exposure to the relatively steady food and beverage sector. This, after Rolfes acquired higher margin Bragan Chemicals – an importer of compounds used in food manufacturing. Apart from the deal being immediately earnings accretive, it has increased earnings diversity at the group, which also sells into the cyclical mining industry. In 2011 Rolfes transferred from the JSE AltX, the market for budding companies, to the JSE Main Board.

Accentuate Limited said it too had managed to increase profits ‘by increasing operational efficiency and reducing operating expenses. Evidence of this was that sales in the first-half to December 2015 were essentially flat, while operating profit was up 46% to R11 million.

Small cap Spanjaard – after a ‘turbulent year’ that included ‘remedial action’ and changes to the board and finance staff – swung back into profit in the year to February 2016.

Meanwhile, battery chemical supplier Delta EMD has not been able to manage its way out of financial trouble, and is planning to close down and delist. However, Delta is not bankrupt and shareholders are still expected to get some proceeds from the sale of assets.

In general, the domestic chemicals sector has few imminent exciting opportunities but has been able to keep its head above water in the current climate. Rand weakness, while essentially a consequence of the struggles at important mining customers, has an upside in that it reduces the threat of competitive imports.

However, the big picture in Africa remains positive. Balance between supply and demand in the metals markets will return as high-cost producers are forced to withdraw. What follows is unlikely to be another commodities super cycle but rather ‘normalised’ dynamics. At the very least, the already established mining industry, which has not shied away from some of the most volatile corners of the world, will again offer an underpin to the chemicals sector.

Sanlam Investments portfolio manager and equity analyst Charl de Villiers says as a general investment theme there are expansion opportunities for the chemicals sector in sub-Saharan Africa. He adds that in addition to mining, there are sales growth prospects in agricultural chemicals.

‘While there has recently been weak demand from farmers – due to the severe drought – the high number of farmers on the continent still practicing subsistence farming will, over time, create new opportunities in nutrients and other chemicals,’ says De Villiers.

However, he cautions that the trajectory of the shift to commercial farming is up for debate. In addition, the agriculture-related food-processing industry on the continent is also creating new markets for chemicals and additives. But, under current economic conditions, the growth of the consumer class is also volatile, says De Villiers.

Many foreign investors focus on the growing African population, including the millions of those who have risen out of poverty. These factors create tempting financial incentives for investing in this market. This includes the expansion of commercial farming on uncultivated land and new food processing capacity.

Although, fears about successfully commercialis-ing rural land – a complex issue in terms of traditional rights and culture – may deter investors and slow the production of the crops needed to supply food factories.

Poor economic management by the governments of key countries, including SA, Nigeria and Angola, isn’t helping sentiment. Historically, crises in the political economy often come to a head during commodity collapses. Investors will hope that when the pressure eases, a bit more sense will return.