It is not surprising that with SA as the world’s largest producer of platinum and platinum group metals (PGMs), the sector is an important one on the JSE. The fewer than 10 companies listed in the sector have a combined market value of more than half a trillion rand.

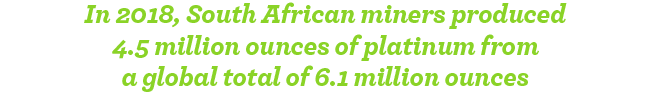

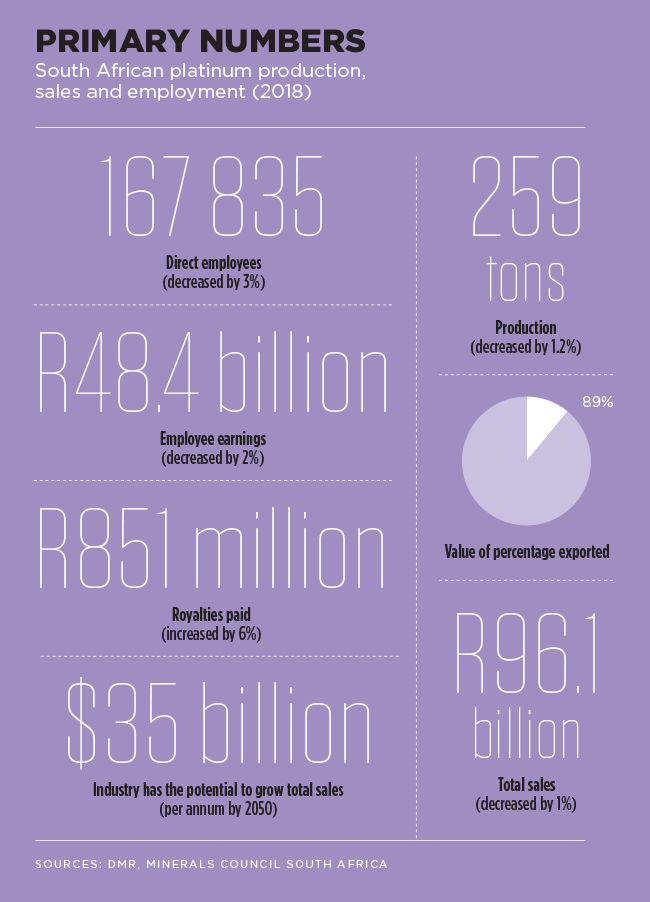

In 2018, SA miners produced 4.5 million ounces of platinum from a global total of 6.1 million ounces, according to the benchmark annual report from major refiner Johnson Matthey (JM). When it comes to other major platinum group metals, Russia is a marginally larger producer of palladium than SA, while the latter accounts for 82% of global rhodium production.

Platinum is found across the so-called Bushveld Igneous Complex in the northern part of the country, and is concentrated in three areas: the western limb surrounding Rustenburg; the northern limb near Mokopane; and eastern limb north-east of Emalahleni. In its 2019 market report JM states that ‘underlying mine output’ in SA ‘rose by around 1% in 2018, despite the closure of two mines in late 2017 and further rationalisation at some older mines on the western Bushveld’.

Peter Major, director of mining at Mergence Corporate Solutions, describes it as a ‘heavy-duty sector’, with ‘pretty substantive companies’ that ‘don’t have a lot to compare to on the gold side anymore’.

Demand for platinum is primarily driven by its use in autocatalysts, jewellery and industrial uses. Investment demand is generally smaller. Demand for palladium and rhodium, by contrast, is almost exclusively (around 85%) from catalytic converters. Both tend to be used in petrol engines, but rhodium is more effective than either platinum or palladium as a catalyst for nitrous oxide.

Anglo American Platinum (Amplats), the largest PGM producer in the world, has a market value of R371 billion, higher than the four gold majors listed on the JSE combined. Also, it is valued at nearly two-thirds the value of its parent, Anglo American (which owns 77.5% of the producer).

The miner has undergone a fundamental transformation over the past five years. Chairman Valli Moosa says this shift ‘from a loss-making, deep-level, labour-intensive mining business to focus on cash-generative, high-margin, open-pit and shallow mechanised operations’ was ‘in response to structural changes in the PGM market’.

It’s difficult to overstate how fundamental a shift this portfolio review was. Amplats shut and sold its most labour-intensive mines (including Rustenburg and Union, as well as its joint-venture operations) following a crippling strike in 2012, and cut 6 000 jobs. Writing in the group’s most recent annual report, Moosa admits that ‘from the board’s perspective, this has been a challenging and sometimes painful process, but the benefits are now clear. The Amplats of today is better positioned for a sustainable future, as its sterling 2018 results demonstrate – PGM production up 4% [to 5.2 million ounces], productivity up 15% and profitability up 21%’.

Its two largest mines, Mogalakwena and Amandelbult, produced in excess of 2 million ounces of PGMs in 2018. By the end of the third quarter, these two mines had produced nearly 1.6 million ounces. Its Unki mine in Zimbabwe and Mototolo in Limpopo, which it acquired outright in 2018, had produced a further 325 000 ounces of PGMs nine months into 2019.

In the year to June 2019, Impala Platinum (Implats) delivered refined PGM production of 3.07 million ounces. Its market value, as at mid-January, was R122 billion. Implats has five mining operations. Three of these – Impala, its primary unit (near Rustenburg); Marula (near Burgersfort); and nearby joint venture with African Rainbow Minerals, Two Rivers – are in SA. A further two are in Zimbabwe: Zimplats (on the Great Dyke near Harare); and Mimosa (further south).

In its annual review for 2019, Implats stated that ‘efforts to maintain open and constructive engagement with the government [of Zimbabwe] will continue amid a challenging economic and political environment’.

In October 2019, Implats bought Canadian PGM miner North American Palladium (NAP) in a $750 million deal. On announcing the transaction, Implats CEO Nico Muller said: ‘Implats has had an exploration presence in Canada for more than two decades and over the past three years we have developed a strong relationship with and understanding of NAP and its management team and operations. Ownership of NAP will accelerate our progress against a number of key strategic imperatives, and it is Implats’ view that the palladium market will remain in a structural deficit in the medium term, which should lend considerable support to stronger-for-longer pricing.

‘The increase in rand PGM pricing, together with the step-change in operational momentum at Implats resulted in considerable free-cash generation and a substantial strengthening of the group’s balance sheet during FY2019. This has allowed Implats to pursue this transaction through a prudent and efficient financing structure and, in doing so, enhance value accretion and returns for the group and its stakeholders, generating returns above the group’s internal cost of capital and with attractive payback periods.’

The deal allowed Implats to ‘further reposition its portfolio and strengthen its competitive positioning in line with its stated strategy by acquiring a palladium-rich, operating asset in an established mining jurisdiction’, acquire a strongly cash-generative asset at a competitive price, and ‘develop a competitive global portfolio of producing, processing and exploration assets’, according to a company press release.

Northam Platinum (with a market value of R71.8 billion) and Royal Bafokeng Platinum (R14 billion) are far smaller producers. Northam’s target is to produce 1 million ounces a year from its three operations – Zondereinde (north of Rustenburg); Booysendal North (on the eastern limb near Groblersdal); and Eland (near Brits), where it is developing the Kukama shaft.

Royal Bafokeng Platinum (RBPlat) comprises the Bafokeng Rasimone platinum mine (previously a joint venture with Amplats, wholly owned since 2019), and Styldrift. The operations are near Rustenburg and ‘situated in the only major shallow platinum group metals reserves still available for mining in South Africa’, according to RBPlat’s website. In 2018, it produced 368 000 ounces and it had produced 299 700 ounces by the end of the third quarter of 2019.

There are four junior producers listed in the sector. Jubilee Metals Group, with a market value of R1.5 billion, is a specialised operator that is focused on re-treating and recovering metals from mine tailings and waste. It has six operations, the bulk of them in SA.

Wesizwe Platinum, majority owned by Chinese Jinchuan Resources, is developing its flagship asset, the Bakubung mine near Rustenburg. It has been ramping up production and hopes to complete this mine and processing plant this year.

Eastern Platinum and Bauba Platinum have smaller operations still. The former treats and re-mines tailings at the Crocodile River mine, while the latter has a chrome mine wash plant in Limpopo.

Sibanye-Stillwater, while not listed in the sector, is the world’s third-largest PGM miner. It moved beyond gold with the 2016 purchase of Aquarius Platinum’s stakes in the Kroondal mine near Rustenburg and Mimosa joint venture in Zimbabwe.

Atlatsa Resources Corporation, which owns the Bokoni mine, is involved in a restructuring plan that resulted in the company delisting from the JSE and TSX.

Given recent soaring metals prices, the sector has been on a tear. CEO Chris Griffith highlighted in the group’s most recent annual report that ‘on a total shareholder return basis, Amplats was the best-performing company on the JSE in 2018’.

The sector continued its exceptionally strong performance in 2019. By the end of October, three of the top five performing shares on the JSE were platinum stocks (Implats, Northam and Amplats). Sibanye-Stillwater was the top performing share then – not unexpected given that it has transformed from a gold producer to a diversified precious metals producer.

Risks remain, though. As recently as May 2019, JM cautioned on the outlook for production from SA, given the ‘risk of industrial action during forthcoming wage negotiations’.

Major says that when considering the attractiveness of an investment destination, the two vectors that require consideration are return and risk. ‘No investor anywhere is going to have SA near the top of the list of 200 countries you can invest in, nor even in the middle,’ he adds, citing the political risk, the massive Eskom issues (cost and stability of electricity supply) and the unstable labour, community and legislative environments.

‘On the PGM front, the quality of the ore bodies in South Africa is the biggest plus we can offer investors. While the mines are robust, they are nevertheless under constant siege.’ But, he says, the recently signed three-year wage agreement is a ‘big plus’, adding that ‘this is a good agreement for employers, unions, stakeholders and government, and so it is no wonder the sector is now the calmest it has been in years’. Details vary from miner to miner, but increases are generally in line with mining inflation of around 7%.

According to Major, ‘these miners now have most of the wind at their back, most importantly stonking high PGM prices’. Platinum is trading exactly at its 120 year average of $930 an ounce, while palladium is at five times its 80-year average and rhodium, at $6 100 an ounce (three times its 80-year average), is nearing highs from the commodities boom in the mid-2000s.

In May last year, JM predicted the platinum market would ‘move into deficit in 2019, with a resurgence in investor activity outweighing modest falls in industrial and jewellery demand’. A ‘tentative recovery in autocatalyst consumption, as stricter heavy-duty emissions legislation is enforced first in China and then in India’ was expected, along with ‘a modest increase in primary supplies, but this could be tempered by electricity shortages and, potentially, industrial action in South Africa, while growth in recycling may be dampened by processing capacity constraints in some regions’.

Longer term, says Implats, ‘as the world focuses on the challenges of decarbonisation, the opportunity presented by fuel cells and a hydrogen economy is gaining growing recognition. The ability to provide zero-emitting, carbon-free energy in electricity and mobile applications through fuel-cell technology is now more widely accepted and took centre stage at the G20 Summit in June 2019.

‘This structural hedge to the expected declining share of pure internal combustion powertrains in the longer term is a vital element to the sustainability of the platinum market’.