There are more than 150 000 spaza shops in SA, visited by 80% of the national population on a daily basis, which accounts for about 40% of total food spend yearly. That’s according to research from Accenture Africa.

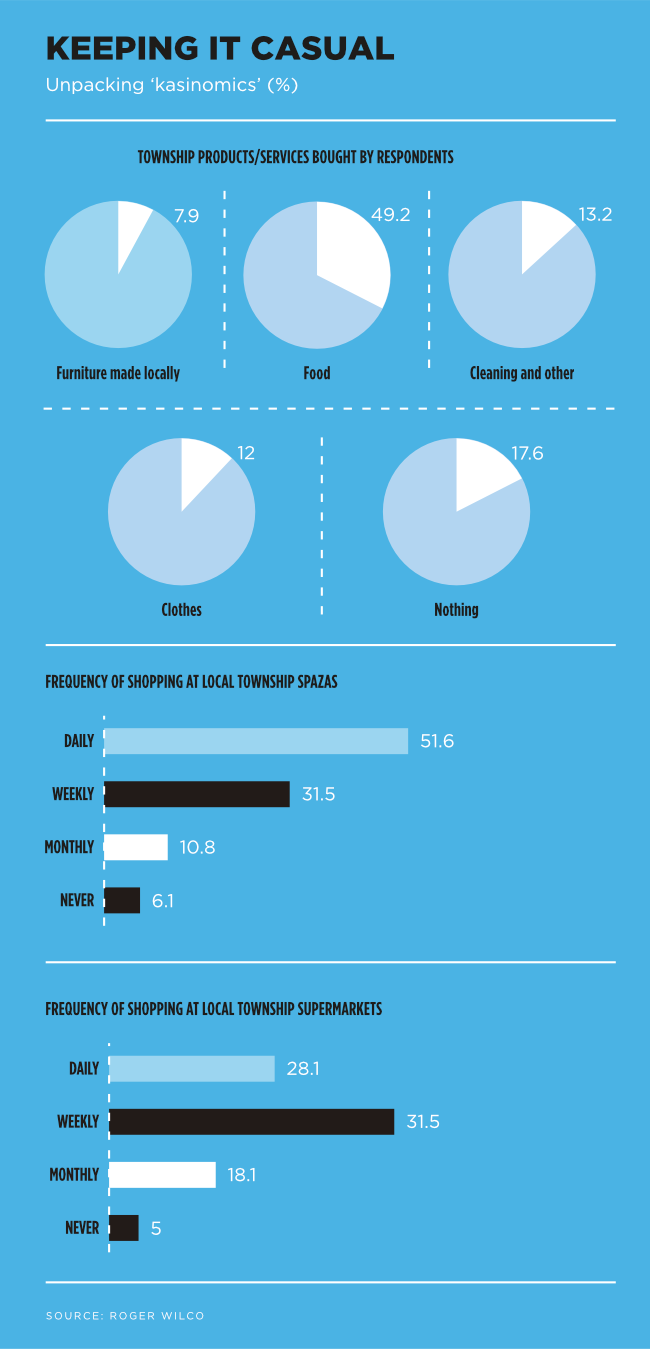

Retail research business Trade Intelligence estimates the informal independent sector is worth R184 billion annually across a range of channels – from pavement hawkers, to home-based spazas and tuck shops, to small ‘midi’ wholesalers. Survey 54 and digital marketing agency Roger Wilco’s 2023 Township CX report data (drawn from a poll of 1 000 people living in townships across the country) showed that township residents prefer to shop close to where they live, with 23% of survey respondents saying they spend 25% to 50% of their income in the township, and a further 25% saying they spend more than 50% of their earnings in the township.

Township, or kasi, communities are also turning to digitalisation to weather some of the toughest storms in the SA economy. The majority (70%) of respondents had made an online purchase, while (60%) said they, or someone they knew, had sold products and services online, or begun working online.

Well-known delivery giants such as Uber Eats, Checkers Sixty60 and Mr D are ‘top of mind in townships’, according to the report, but ‘we are also seeing the rise of eKasi Delivery, which has been used by 12% of respondents, and Hammanskraal-based Delivery Ka Speed with 5% of respondents saying they have interacted with it’.

In his latest book published earlier this year – Born White, Zulu Bred: a Memoir of a Third World Child – ‘kasinomics guru’, as he calls himself, GG Alcock brings this vibrant, industrious segment of SA society to life. ‘Most people think of the township or informal economy as rows of hawkers, their wares laid out on cardboard carpets on pavements or on rickety tables crammed cheek-by-jowl on the peripheries of taxi ranks. Or they think of spaza shops, little hole-in-the-wall or backyard corrugated iron structures, their dark insides filled with daily necessities, small sachets and outdated foodstuffs.

‘They don’t think of Nomhle, who has converted the yard of her inherited fourroom house and built a two-story block of six amaroomi, backrooms which she rents out at R2 000 per room. Or Mbali, who has three roadside Chicken Dust outlets, literally a row of braai drums under a colourful stretch fabric tent, and sells more than a thousand grilled chickens a week, buying them for R40 and selling them along with a salad and maize meal pap for R110. What about Justice, who sources the chickens that Mbali grills from a grower, along with bags of potatoes from the market, and 20-litre cooking oil drums and delivers them to Mbali in a few hours, whenever she sends her WhatsApp order?’

Needless to say, the informal sector – ‘which mirrors every sector in the formal sector, just trading differently’, according to Alcock – is ripe for development and presents an enormous opportunity for partnership with corporate muscle.

In August, Tiger Brands announced its intention to expand its presence in the informal sector by implementing robust route-to-market support across 130 000 general trade store customers, including spazas and midi-wholesalers, over the next five years. To date, the company has reached more than 46 500 general trade outlets with a target of 50 000 by the end of the year.

In addition, the packaged goods company is working with customers to create ‘Perfect Outlets’ in the general trade, with investments in point-of-sale marketing execution across their basket, and branded coolers to improve cold availability of Tiger Brands’ ready-to-drink beverages. The aim is to establish 2 000 Perfect Outlets over the next five years.

‘We are leveraging the existing network of wholesalers and distributors and partnering with them to penetrate the trade,’ says Luigi Ferrini, Tiger Brands’ chief customer officer.

‘These midi-wholesalers operate within a community of spaza stores and we partner with all viable outlets,’ he says. ‘This initiative started two years ago when we piloted various models before settling on the current ones, rolling them out across South Africa. The business has achieved significant growth in this market to date. In Tembisa, for example, Tiger Brands’ consumer basket has increased by 185.7%, from 28.5% in 2020 to 97.3% currently.’

Tiger Brands and its partners have created around 198 jobs within communities where it is executing this growth strategy and aims to have created a further 74 jobs, taking the total number of jobs to 272, by the end of September 2023. A large proportion of these are women. In Tembisa alone, at least 60% of all new jobs created are occupied by women.

‘Shopper behaviour has shifted significantly over recent years, with many seeking increased convenience and better value,’ says Ferrini. ‘Because of the informal traders’ in-depth understanding of their consumer base, they are well placed to service the consumer’s needs. In addition to this, the informal market is growing at a faster rate than modern markets. As a business, if we want to grow strategically, this is the market in which we need to invest, without question.’

Tiger Brands’ introduction of mobile cashless payment and order platforms allows spaza traders to place a stock order with a mini- or midi-wholesale and to pay for it via an e-wallet system. ‘The order is fulfilled within 48 hours,’ says Ferrini. ‘This system allows, among other benefits, the ability for the trader to save on additional costs, which in turn offers more affordability for the consumer. This system places orders, picks orders, pays for orders and executes delivery of products.’

In 2016, Pick n Pay launched its pilot Spaza-to-Market Store in partnership with SA’s Department of Economic Development, with the aim of revitalising and modernising spaza stores to drive growth by providing spaza shop owners with access to Pick n Pay’s procurement and distribution channel, business systems, technology and management advice and mentoring.

As of 2022 the supermarket giant has developed 36 of these stores, opening five new stores in FY 2022; however, seven underperforming stores were closed, including one store unable to recover after the devastating civil unrest in KwaZulu-Natal and Gauteng in July 2021. The group will focus on optimising the market store operating model in the year ahead.

Circa 2019, Shoprite added eKasi box stores to its established uSave chain of small-format, low-cost stores in township areas. eKasi stores are housed inside a handful of easy-to-transport shipping containers, allowing stores to be opened in previously unviable locations, and carry up to 950 basic products. In 2022, uSave reported growth in sales for the year of 11.4% (greater than Shoprite stores’ growth of 6.7%), and ended the FY 2022 with 36 eKasi stores.

‘Private sector support is imperative, more so because government can’t do it on their own due to limited resources,’ says Bulelani Balabala, the founder of the Township Entrepreneurs Alliance. ‘I appreciate and thank corporates that have played a role in this space and encourage others to come to the party,’ he says. ‘I would like to see more corporates not just supporting but being intentional about long-term impact and sustainable programmes.’

One of the shifts Balabala has noticed is that the backyard-room market has grown. This market used to cater to very low-income earners, but now offers dignified living to professionals and families, he says. There is also an increase in the consumption of local products, signifying a change in how people who grew up in the township view local products.

‘We need to stop trying to define the market from the outside. The informal market might not follow the usual formal structures; however, it’s one of the most formal markets you will come across. What we need to do is to understand it. Once we understand it, we need to plug into the community, and then call in the correct implementation partners and deliver,’ says Balabala.

Defying conventional definitions, township economies represent an unprecedented opportunity for development and transformation, driven by kasipreneurs who have built better lives for themselves and their communities.

The caveat for big business is to tread carefully, refraining from displacing – rather than integrating – established small enterprises, working with them to improve efficiency, products and prices.

Alcock’s perspective reminds us to celebrate the remarkable spirit of the individuals and groups who have created a sustainable niche for themselves in a challenging environment. ‘Our informal or kasi South Africa is better off than we realise, economically, lifestyle wise, productivity wise,’ he writes.

‘It is a space where despite circumstance these amazing entrepreneurs, homeowners, traders, have built a better world, and continue to do so, ignoring the government, the formal business community, doing without formal employment or in addition to it. They are the kasipreneurs, and they have the power to transform South Africa and will continue to do so.’