In August, Anglo American announced the donation of its 45 Main Street building in Johannesburg, situated in the central business district, to the Maharishi Invincibility Institute, a non-profit private education institution dedicated to empowering underprivileged youth in the inner city and surrounding areas.

The move is intended to allow the institute to extend its impact, benefiting up to 3 000 youngsters – more than doubling the number of students it can support. The institute focuses on access to on-the-job training for students and actively works to help graduates secure sustainable jobs at some of the country’s leading corporates.

This is but one of countless life-changing interventions from the private sector – not to mention government and civil society – aimed at reducing high youth unemployment in the country, a seemingly intractable problem that was described as a ‘ticking time bomb’ as far back as 2011.

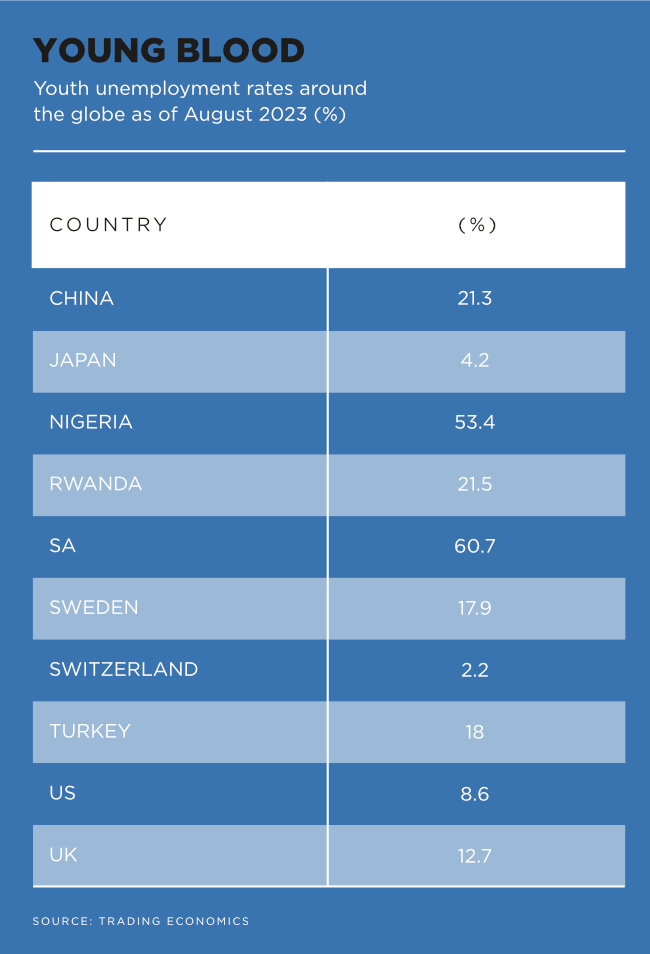

Yet the scourge of unemployment among South Africans aged 15 to 34 continues to rise… And rise… And rise. Nearly half of all young South Africans are currently unemployed –45.3% (Q2 2023). This figure shows that not only has unemployment not recovered to pre-pandemic levels (2019 Q4: 40,1%), it has grown progressively worse – 2020 Q4: 41.8%; 2021 Q4: 44.7%; and 2022 Q4: 45.3%.

(If you’re wondering why an employment survey includes children of school-going age, bear in mind that youth who are still in school, studying at a tertiary institution, and/or are not actively seeking employment, are not included in these figures.)

How can this be, when so many government initiatives, corporate programmes and NGOs exist for the sole purpose of building a bridge for the jobless youth to the promised land of economic inclusion? Is the problem simply too immense; the strategies used ineffective?

‘Unemployment is primarily caused by the lack of economic growth – and South Africa has had 1% GDP growth on average for the last 10 years, compared to the 5.4% that it needs,’ says Ravi Naidoo, CEO of the Youth Employment Service (YES), a private sector-led initiative that created 32 578 youth jobs in 2023 alone. ‘In such an environment, unemployment rates will be higher for young people who lack work experience. Youth unemployment is also exacerbated for those from under-performing schools. The net result is that in the [financial] year to March 2023, approximately 700 000 youth entered the labour market while the economy created only an additional 139 000 jobs for people aged 18 to 34.’

YES has created more than 120 000 youth jobs since inception in 2018, paying R6.2 billion in salaries, which are 100% funded by the private sector, says Naidoo. As a programme focused on one-year, full-time ‘internships’ (which YES legislation defines as quality work experiences), YES is the largest programme of its kind in SA. Moreover, with more than 1 550 corporate sponsoring partners, it is now the most corporate-supported social impact programme in the country.

Marc Lubner, CEO of Afrika Tikkun Group – a non-profit that cares for vulnerable children in townships using a cradle-to-career approach – offers this perspective: ‘The reason many NGO and governmental initiatives, as well as CSI programmes, are not moving the needle, is because we are all operating independent silos. There is significant duplication of costs, and typically most services are offered within a few concentrated areas, invariably close to where corporates are operating.

‘My belief, over the 18 years I have been in this field, is that the development of a productive youth force requires an early intervention in children’s development. Most youth emanating from poverty-stricken environments grow up in a culture of victimhood, believing that their circumstances will not change,’ he says.

‘The democratic system that their parents fought for has failed to deliver job opportunities. Therefore, to cultivate a productive young adult, you have to invest in the various life phases leading to young adulthood. This involves teaching values and discipline at an early age,’ says Lubner.

‘As a child matures, so they need to learn to believe in themselves and the decisions they make. They need basic education that enables them to make wise career decisions. They need exposure to the various career opportunities that exist outside their impoverished environments, as well as within. Throughout this period, they need nutrition, health, encouragement, sport/recreation and a sense of purpose. They need to be loved in a healthy and productive way. If all our “contributing” parties aligned around this cradle-to-career model, we would see better outcomes in terms of a more productive work force. If corporate South Africa would define the jobs and values that they are looking for well in advance of training, civil society organisations and educational institutions could orient towards a more impactful result.’

Afrika Tikkun itself has an impressive track record, in part made possible by donations from a multitude of private-sector interests,from Huawei to Liberty Life, KFC, Pick n Pay, Absa, Barloworld, Maersk, Coca-Cola and others. The organisation currently has about 7 000 children and youth attending its centres through child and youth development programmes, and reaches a further 3 000 to4 000 early childhood development (ECD) learners through its Bambanani outreach programmes, plus an additional 1 000 youth through outreach to schools neighbouring its centres.

Around 8 000 young adults attend Afrika Tikkun’s job skills training and work experience programmes. Approximately 60% of the graduates of Afrika Tikkun centres qualify with university pass rates, and about 6 500 individuals are actively involved in the organisation’s alumni programme, which provides ongoing support.

Currently, Afrika Tikkun is trying to scale its impact beyond its existing owned and operated sites, says Lubner. ‘We are sharing our IP in communities across the country, who are helping to formulate coalitions within geographies where other community-based organisations are operating independently. We’re motivating corporates to work in sync with local government in these areas, so that jobs can be promised to those appropriately trained. It is only when the various forces at play combine together that we will experience the impact that we are looking for in youth employment.

‘Government equally needs to stop fragmenting this sector by inviting competitive bids from civil organisations, and should rather motivate a sharing of competencies and skills by awarding contracts to such coalitions.’

One cannot talk about youth unemployment without talking about education. Literacy and numeracy indicators among school learners are concerning, to say the least. The 2023 Reading Panel Background report notes that that less than 50% of Grade 1 children learn the letters of the alphabet by the end of that grade. The report also estimates that 82% of Grade 4 pupils struggle to read for meaning. The most recent Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study, in 2019, found that at primary school level, SA had the third-lowest score out of the 64 countries, while Grade 9 learners received the second-lowest score out of 39 countries. A recent study from the Cape Peninsula University of Technology found a significant gap between high school and university maths for science and engineering students, with learners entering institutions of higher education unprepared.

‘A new law recently introduced by the DoE allows learners to leave school at the end of Grade 9 with a General Education certificate [GEC] to reduce failure, repetition and drop-out rates in schools,’ according to Kelly Joshua, head of education investing for Old Mutual Alternative Investments (OMAI).

‘While the GEC is not regarded as an exit point for school but a pathway to one of three streams – academic, technical vocational and technical/occupational – it is another step towards solving the skills deficit,’ she says.

How could leaving school earlier be better? The positive spin-off of the GEC, says Joshua, is the intended changes to the curriculum, including technical occupational subjects such as electrical, mechanical, civil technologies and engineering graphics and design.

‘It will also introduce new topics such as technical mathematics and technical science. While this law aims to improve the quality and efficiency of education in the country, it requires careful planning, implementation and support from all stakeholders involved.’

The first field trial for the GEC is scheduled for completion by 2024 and will be rolled out to all schools by 2025, she adds. The concern is that the reform does not compel learners exiting Grade 9 to continue with the academic stream or to enrol in a technical and vocational education and training college, or a skills development programme from a private training provider. At present, many learners exit the system with a Grade 9 pass, but are often considered very young for employability.

‘Even those with a National Senior certificate without a bachelor’s degree pass in mathematics and science are not eligible to pursue a tertiary qualification in the disciplines that are in demand. They are, therefore, no better off than learners who do not complete matric.

‘Additionally, these youth still need to be physically, emotionally and psychologically developed for the world of work and need more essential life skills, behavioural competencies and soft skills.’ There is a pressing need for enhanced learning environments that are accessible, in particular in low-income communities, she adds.

OMAI has two education impact funds that currently support 45 schools across SA, catering to 23 000 learners and employing 1 600 teachers. These investments are mandated to primarily target lower-income communities to foster local employment, gender equality and environmental sustainability. Recently, OMAI pledged R400 million to the Tutuwa Community Trust, an organisation established to support ECD, schooling and post-schooling work readiness.

‘Having a university degree or tertiary education is also no guarantee of employment,’ says Anton Visser, group COO of Alefbet Learning, which incorporates SA Business School. ‘This is where learnerships play a critical role – [they] create well-rounded candidates who have a good grasp of all the work processes. For the learners, employment prospects are imminently better with sound theoretical and practical occupation-specific training backed by a nationally recognised NQF qualification. At the very least, there is far greater opportunity within the broader industry sector with a qualification and on-the-job experience.

‘Businesses can make a fundamental difference by investing in learnerships, which bridge the gap between the current education provided versus what is needed by the labour market and employers. They’re central to skills upliftment in South Africa and in bringing young people onto the employment ladder and into solid career and employment trajectories.’

On its own, says Naidoo of YES, no single programme can directly generate enough youth jobs to compensate for the lack of economic growth. However, he adds, if programmes are catalytic in their structure, they can have a longer-term multiplier effect that far exceeds the direct jobs created.

‘If we get as many of our talented youth as possible into meaningful roles in the economy, they will be able to generate the jobs and future-facing businesses that South Africa so desperately needs. This can be done by creating a talent pipeline for young people from poor households to enter the economy.

‘It’s now more important than ever that we create opportunities for youth who have the potential to forge successful careers, start businesses and fill the socio-economic gaps in communities.’