‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going.’ While this line may bring thoughts of R&B artist Billy Ocean’s 1986 hit to mind, the phrase has apparently been around since the 1950s, coined by an American football coach during a locker room talk. Essentially, it alludes to the fact that when faced with adversity, strong individuals will rise to the occasion. In today’s world, however, it can mean quite the opposite.

Enter the concept of tang ping, which, in Chinese, refers to a new lifestyle that bucks oppressive work culture. The trend was apparently ignited by a (since deleted) post on a popular Chinese microblogging site in 2021. ‘Lying flat is my wise movement,’ a user wrote. ‘Only by lying down can humans become the measure of all things.’ It’s a sentiment that has gained rapid momentum among China’s Gen Z, resulting in a movement of youths who are opting out of the rat race – economically and socially. The lying flat concept rejects getting married, having children, having a job and owning property.

‘For many, this is almost the only way in an authoritarian country to fight against the growing pressures from long work hours, sky-rocketing housing prices, and the ever-higher cost of raising children,’ Wu Qiang, an independent political analyst in Beijing, told Quartz.

‘Lifestyle philosophies based on rejecting ambition, and being a cog in China’s capitalist machine, have been spreading in recent years, and “lying flat” is the latest culmination of such trends.

‘Chinese youngsters, or in general the working population, have experienced huge societal and political changes in the past nine years, [leading them to realise] that there is neither the possibility for initiating a revolution nor the freedom of expression. Under such a condition, lying down has become the only option.’

China’s shrinking labour market has placed younger individuals under immense pressure, necessitating that they work significantly longer hours, ultimately resulting in burnout. Add to this the devastating knock-on effects of COVID-19 restrictions, and you have a recipe for disaster.

With a population of 1.4 billion, close to 30% are between the ages of 20 and 40, and their significance in the labour market is expected to increase, particularly considering the demographic shifts caused by the nation’s former one-child policy, resulting in a shrinking working-age population in the coming decades. The OECD forecasts that, by 2035, 20% of China’s population will be over the age of 65, adding more pressure on young people to support older generations.

Lying flat shares many similarities with the great resignation, a trend that also emerged in 2021. According to the WEF, the term was coined by Anthony Klotz, a professor in the US, who explained it as ‘a wave of resignations as people digested the lessons of [COVID-19] lockdown and re-imagined what normal life should look like. After working from home for months, with no commute and more time with family, many people have decided it’s time for a change’.

In August 2021 alone, 4.3 million US employees, equivalent to 2.9% of the total workforce, made the decision to resign from their jobs, an unprecedented peak, according to the US Bureau of Labour Statistics.

The WEF’s Global Risks report 2023 lists youth disillusionment among the top 10 societal risks; and according to the 2021 edition of the report, deteriorating mental health since the start of the pandemic left 80% of young people worldwide vulnerable to depression, anxiety and disappointment.

‘South Africa is no exception to the rest of the world but has local nuances that are playing out largely because of our massive unemployment rate,’ Chris Blair, chief executive of remuneration and HR consultancy 21st Century, is quoted as saying in a 2022 BusinessTech article. ‘We have a 35% unemployment rate and 65% youth unemployment – so why would people resign in a market with a huge oversupply of labour?

‘Traditionally the number one reason for resignation has been better pay followed by better career opportunities and development. This trend has flipped, where only approximately 20% now resign for better pay, while more than 70% resign for a better work-life balance, flexibility, career development and a healthier culture and leadership.’

According to Blair, these factors have contributed to the increase in the prevalence of ‘contingent workers’, who generally typically have limited job security, receive cash payments without benefits, are compensated on a project or contractual basis, and are paid based on their output or time worked.

‘Contingent workers come with many names – freelancers, consultants, contractors, non-permanent workers, temporary staff and independent workers,’ he says. ‘A lot of these new contingent workers put the quality of living ahead of salaries and make up the difference in the previous premium income by living in lower-cost areas, travelling less, and having simpler family-focused lives.’

Then, of course, there’s the ‘quiet quitting’ concept, which, says the WEF, ‘doesn’t mean actually quitting your job. It just means doing what’s required and then getting on with your life – having more work-life balance’. It also describes quiet quitting as a way of dealing with burnout.

Consultancy Gallup, in its 2023 State of the Global Workplace report, notes that just 23% of world’s employees find their work meaningful and feel connected to the team and their organisation. On the other hand, a staggering 59% are not engaged (quiet quitting).

‘These employees are filling a seat and watching the clock. They put in the minimum effort required, and they are psychologically disconnected from their employer,’ it states. ‘Although they are minimally productive, they are more likely to be stressed and burnt out than engaged workers because they feel lost and disconnected from their workplace.’

The remaining 18% of employees worldwide are actively disengaged. ‘These employees take actions that directly harm the organisation, undercutting its goals and opposing its leaders.’

Gallup estimates that low engagement costs the global economy $8.8 trillion and accounts for 9% of global GDP.

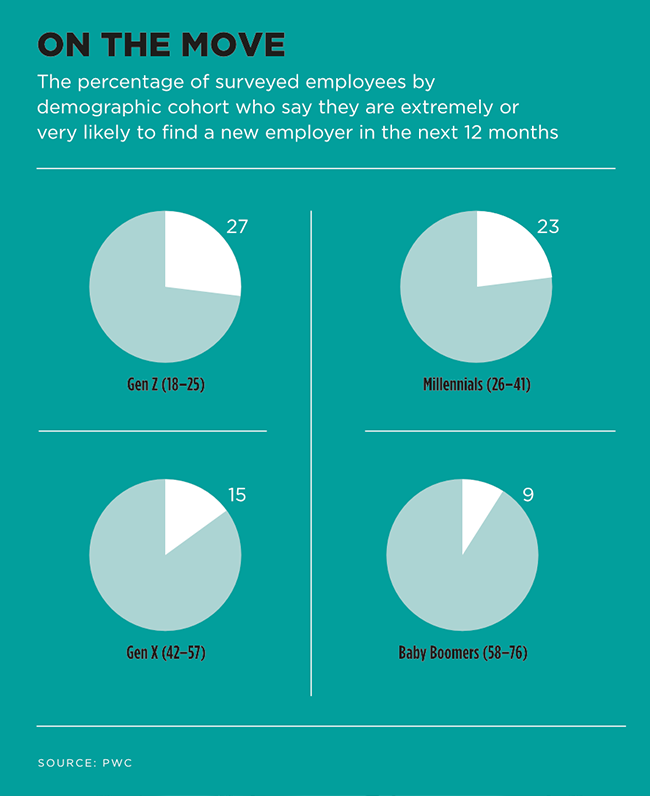

‘If the “great resignation” has taught employers anything, it’s to not take their workers for granted,’ according to PwC. ‘Yet many companies risk doing exactly that – whether it’s by not paying close enough attention to skilled workers who are at elevated risk of quitting, by failing to support workers who seek personal fulfilment and meaning at work, or by missing opportunities to build the trust that so often leads to positive outcomes at the personal, professional and even societal levels.’

PwC research found that the workforce represents the primary risk to growth, yet it’s also a key avenue for companies to implement growth-oriented strategies. Having a good understanding of the dynamics of workplace power enables leaders to motivate their workforce, harness the potential of their employees and achieve more ambitious objectives.

That relationship between the employer and employee is, after all, a two-way street. It’s critical to create an environment in which, when the going gets tough, the tough are motivated to stick around.

By Nicola-Jane Ford

Image: Gallo/Getty Images