As employees head back to work for the start of the new year, it would be great to believe everyone is returning feeling rested, positive and energetic. In an ideal world, that is. The truth is many people will be heading back to the grindstone with trepidation, particularly if that employee is suffering from burnout.

Once considered a buzzword for overworked professionals, burnout has transformed into a pervasive issue that infiltrates workplaces across industries. It’s not just about being tired – it’s a multifaceted issue impacting mental health, organisational productivity and the very fabric of workplace culture.

The term ‘burnout’ was coined in 1974 by psychologist Herbert Freudenberger, who described it as ‘the extinction of motivation or incentive, especially where one’s devotion to a cause or relationship fails to produce the desired results’. And who is prone to burnout? ‘The dedicated and the committed,’ he said.

The WHO officially recognised burnout as an ‘occupational phenomenon’ (albeit not a medical condition) in 2019, characterising it as a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that hasn’t been effectively managed. Yet, despite growing awareness, burnout continues to rise, leaving employees exhausted, disengaged and downright disillusioned.

Renata Schoeman, a professor and head of the healthcare leadership MBA at Stellenbosch Business School, argues that burnout is a workplace phenomenon that should not be confused with daily stressors of everyday personal life responsibilities. In an online post, she writes that ‘burnout is a persistent feeling of physical and emotional exhaustion that frequently comes with pessimism and disengagement from work. The culprits are usually an imbalance of resources and/or demands on what is expected of you at work versus the availability of time, finances, training, support systems, mentorship and other resources needed for you to do your job’.

Burnout is typically identified through three key dimensions – emotional exhaustion, characterised by feelings of being emotionally drained and depleted; depersonalisation (a sense of detachment or cynicism towards the job or coworkers); and reduced personal accomplishment, with a diminished sense of efficacy and achievement in work.

This trifecta makes burnout a uniquely debilitating experience, unlike mere stress, which can sometimes motivate action. Burnout leaves individuals paralysed, unable to muster the energy or enthusiasm to meet daily demands.

The 21st-century workplace has created conditions ripe for burnout, and several systemic factors exacerbate the problem. For one, global economic shifts, job insecurity and the rise of gig work (income-earning activities outside of standard, long-term employer-employee relationships) have amplified stress. Many workers are taking on multiple jobs or longer hours to make ends meet, often sacrificing rest and self-care in the process.

The ‘always-on culture’ certainly hasn’t helped either, with the proliferation of technology blurring the lines between work and personal life. Emails, instant messages and project management tools create an always-on expectation, where employees feel compelled to be available outside traditional working hours. This digital tether creates a never-ending loop of responsibilities, making true downtime increasingly elusive.

The COVID-19 pandemic, too, accelerated burnout in unprecedented ways. Remote work blurred boundaries further, care-giving responsibilities increased, and fears around health and job stability added new layers of anxiety. Although remote work offers flexibility, it has also created isolation and heightened workloads for many employees.

And, of course, high-pressure environments with unrealistic performance expectations, tight deadlines and constant competition have a tendency to push employees to their limits.

Meanwhile micro-management and rigid hierarchies can leave employees feeling powerless. And when workers have little control over their schedules, tasks or decision-making processes, it breeds frustration and helplessness – key ingredients for burnout. ‘Another contributing factor is conflicting values – either a mismatch between your personal values and the organisational values, or, the officially stated values of the organisation and the values in action,’ says Schoeman.

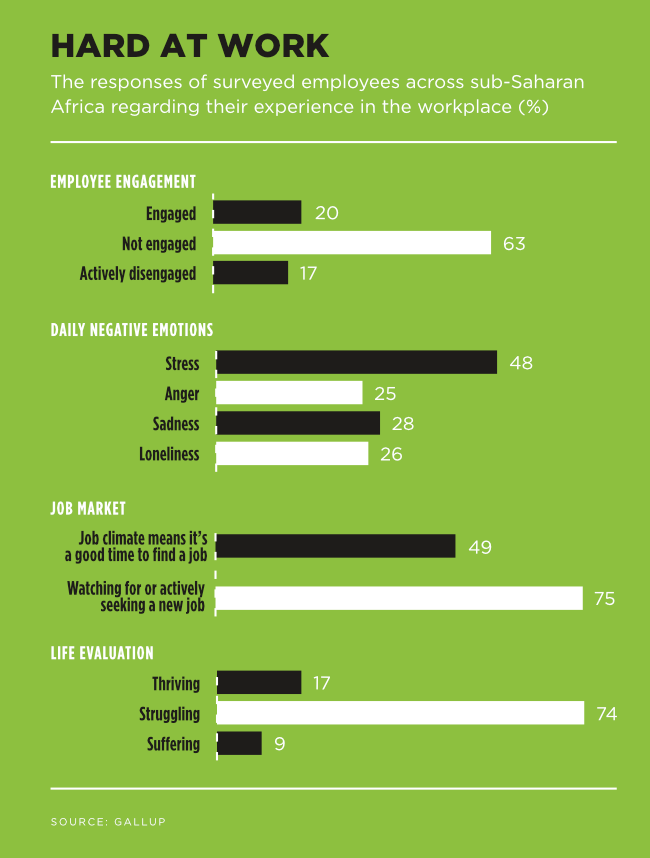

According to a Gallup study, ‘28% of full-time employees reported feeling burned out at work “very often” or “always”. An additional 48% reported feeling burned out “sometimes”. That means most full-time employees — nearly eight in 10 — experience burnout on the job at least sometimes’. The report also notes that burned-out employees are 63% more likely to take sick days and 23% more likely to visit the emergency room.

Burnout is a productivity killer. Disengaged employees struggle to focus, miss deadlines and underperform. It is also one of the leading causes of voluntary turnover, especially among younger generations such as millennials and Gen Z.

‘Younger millennials and Gen Z were raised with a lot of pressure to be high achievers, but are starting their careers in a chaotic landscape where they have little autonomy and freedom to find a meaningful, well-paid job,’ according to Debbie Sorensen, a US-based psychologist, pointing to companies’ ever-changing return-to-office policies, proliferating layoffs and hiring freezes as the leading contributors to burnout for these generations.

Women are also reporting higher levels of burnout than men, a gap that has more than doubled since 2019, according to Gallup. ‘In 2019, 30% of women and 27% of men said they “always” or “very often” felt burned out at work. That three-percentage-point gap expanded to 12 points in the pandemic-era months of 2020, from March to December, and averaged eight points in 2021 – 34% of women and 26% of men reported feeling burned out.’

The explanation for this widening gap can be boiled down to gender inequities. Women are less likely to be promoted than men yet more likely to head single-parent families and take on unpaid labour – all things that can exacerbate burnout. Women in non-leadership positions are especially affected.

The personal toll of burnout is severe. Prolonged exposure to chronic stress can lead to depression, anxiety, cardiovascular disease and weakened immune systems. Sleep disorders, substance abuse and even suicidal ideation are not uncommon among those experiencing severe burnout.

Yet burnout doesn’t only affect the individual – it reverberates across teams, organisations and even economies. A 2023 Investec report notes that unaddressed mental health conditions cost the SA economy an estimated R161 billion per year, as a result of lost days of work on account of illness, ‘presenteeism’ (working longer hours), and – in extreme cases – premature mortality. In that same year, low employee engagement cost the global economy $8.9 trillion, or 9% of global GDP, according to Gallup estimates.

The direct cost of burnout, says Schoeman, ‘leads to increased absenteeism, reduced productivity, poor work performance, mistakes and high employee turnover – all quantifiably impacting the organisation’s bottom line’.

Then, of course, there’s the hidden cost, namely ‘the institutional loss of knowledge when employees leave, the time and cost spent on training and upskilling new employees, and the negative impact on organisational culture. Once an organisation is known for its toxic work environment, it will be difficult to attract top talent’, she writes.

Organisations face significant costs when employees leave due to burnout. Recruitment, onboarding and training new hires is expensive, and the loss of institutional knowledge can be devastating. Yet, perhaps more importantly, burnout erodes workplace culture. It fosters resentment, reduces collaboration and diminishes morale. When employees feel unsupported, it creates a ripple effect, affecting overall team dynamics and engagement.

Navigating the complexities of this serious issue in an era defined by rapid change, high expectations and dwindling boundaries between work and life requires a multi-level approach to breaking the burnout cycle. After all, burnout is not an individual failing – it’s a systemic issue, and solving it requires a collective effort.

Leaders, in particular, play a pivotal role in combating burnout. Leadership should involve regular check-ins with team members to assess workloads and morale. Simple questions such as ‘how can I support you?’ or ‘what’s feeling overwhelming right now?’ can open pathways for early intervention.

Providing managers with training on recognising and addressing burnout is also essential, while access to mental health resources, such as employee assistance programmes and counselling services, can help employees cope with stress.

Companies should actively discourage the ‘always-on’ mindset by setting clear boundaries around work hours. Policies such as ‘no emails after 6 pm’ or designated ‘unplug days’ can reinforce the importance of downtime. Creating an environment where employees feel safe to voice concerns without fear of retaliation is also crucial. Leaders should encourage open dialogue about workload, stress and mental health.

Hybrid work models and flexible hours, meanwhile, can empower employees to manage their time effectively, balancing personal and professional responsibilities. And streamlining workflows to eliminate unnecessary tasks, reduce micromanagement and promote autonomy can also significantly alleviate stress.

The onus to reduce employee burnout is not solely on the business, however. Organisations should lead the charge by making systemic changes, but individuals must also advocate for their own well-being by setting firm boundaries, such as not answering work emails during personal time. Learning to say ‘no’ is a critical skill for avoiding overcommitment. Reconnecting with the ‘why’ behind one’s work can also help restore motivation and meaning. If the current job doesn’t align with personal values, it may be time to explore new opportunities.

Ultimately, workplace burnout is more than an occupational phenomenon – it’s a public health crisis that demands urgent action. Prioritising mental health, rethinking workplace norms and fostering supportive cultures, would go far in reversing the burnout epidemic, creating environments where individuals and organisations can thrive together. Perhaps it’s time to redefine ‘success’ as sustainable, meaningful work that supports both well-being and innovation, instead of constant productivity. After all, the cost of inaction is far greater than the investment in change.