It was 8 am on a bright clear morning. To the left, just short of a ridge, a cow and her calf appeared. It seemed like a good idea to capture a few cattle while chasing down the outpost impis they had been pursuing, so Lieutenant Charles Raw of the Natal Native Horse led his mounted men in pursuit. As they crested the ridge, what lay beyond froze their blood.

Sitting perfectly still in the short grass were upwards of 20 000 Zulu warriors. As James Hamer, a civilian transport officer among the riders later wrote: ‘On coming up we saw the Zulus, like ants, in front of us, in perfect order as quiet as mice and stretched across in an even line.’

Their cover blown, the warriors rose up and headed across the fields of the Nqutu plateau towards the now-infamous British army settlement under the jutting peak of Isandlwana. It was 22 January 1879, and the British were heading for their worst defeat of the Anglo-Zulu War, a conflict that would change the political shape of the country.

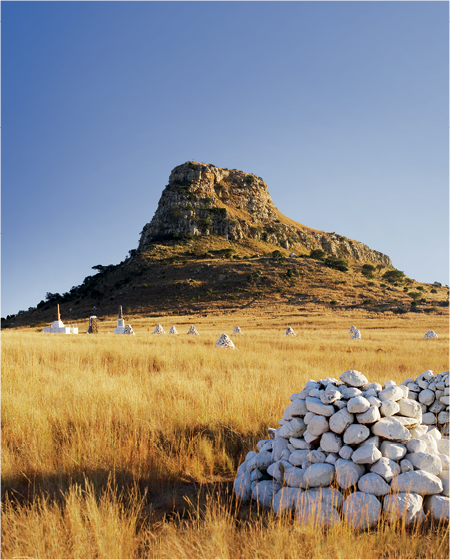

Standing on the now deserted plains of the battlefield, it’s difficult to imagine the numbers or the carnage that claimed 1 300 British and 1 000 Zulu lives that summer’s day. A breeze bends the patchy grass and the white cairns, in memorial to those who died, stand counterpoint to the bleak landscape and rising rocks.

Rob Gerrard, Isandlwana Lodge’s resident historian, has given an edge-of-the-seat account of the lead up to the battle and is now detailing the consequences of the Zulu king Cetshwayo’s victory over Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford. It was to focus the British, harden their attitudes and intensify their assaults. Eight months later Cetshwayo was on Robben Island and the Zulu kingdom in the hands of the British, parcelled out to puppet chiefs in the pockets of the colonisers. The Boers were next, nearly a quarter of a century later, and many of those battles were fought in the area.

SA history, rich and complex, was especially intense during the late 19th century, as the British sought to extend their Cape-based rule across the subcontinent. The Anglo-Zulu and two Anglo-Boer Wars, between 1879 and 1902, defined 20th century SA history and shaped global warfare for the conflicts to come. On the windswept plains of Dundee and Colenso, guerilla warfare was being perfected, future leaders made (Gandhi, Smuts, Churchill), set-piece warfare consigned to the dustbin and highly mobile warfare born. Many suggest it was the beginning of the end of the British Empire.

No surprise then that this determining period is very popular for travellers, keen to visit the sites of such pivotal events. And for the discerning aficionado, there are a number of five-star lodges in the area offering a mix of history, luxury and pampering.

Most are in current day northern KwaZulu-Natal, the site for not only the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, but of many major Anglo-Boer War battles such as Talana Hill, Elandslaagte, Ladysmith, Colenso, Spioenkop and Vaal Krantz.

It’s difficult to imagine the numbers or the carnage that claimed 1 300 British and 1 000 Zulu lives that summer’s day

Gerrard is the reason most find their way to Isandlwana Lodge. Rob is a natural storyteller and the Anglo-Zulu conflict comes alive in his hands. Groups sit on comfortable chairs for the pre-site visit lectures and by the conclusion, everyone is itching to head off to the battlefield and see for themselves how the manoeuvres Rob had just outlined, actually happened.

Rob comes from an English background, an ex-Gordon Highlander with years in the army, so he knows his stuff. Later, at Isandlwana, his intimate knowledge brings to life the day’s events. It’s hair-raising.

The lodge itself, atop a hill for panoramic views, is a trove of Africana memorabilia, stacked with mementos of the area, its history and the owners’ personal travels. It is vintage safari in its design – stone, wood and thatch predominate, with the accent on space. There are magnificent views from the various expansive decks, looking across to the battlefield. The rooms also boast those views, with their own decks and want for nothing in terms of comfort and indulgence.

Not far away, Fugitives’ Drift is the home of Nicky Rattray and her son Andrew, who has taken up the guiding reins after the legendary David Rattray was killed in 2007. His death, at the hands of an intruder, brought to a halt a life dedicated to the region’s history, natural abundance and, more importantly for David, the region’s people.

Through the David Rattray Foundation his work goes on, funding various initiatives in the area. David’s major contribution, however, was redefining how the stories and history of the wars were told, with more research and understanding of the Zulu and Boer sides. Fluent in Zulu, he was a force of nature on the battlefields, uncovering hidden aspects of the history that lay untold for years. His son Andrew now extends the Rattray legacy – just as passionate, just as knowledgeable and just as balanced. It’s heartening seeing him fill his dad’s shoes so well.

Fugitives’ Drift is on a 5 000 acre reserve, bordering the two battlefields of Rorke’s Drift and Isandlwana. Fugitives’ derives from the ford where fleeing colonial soldiers crossed the Buffalo river back into British Natal after the rout at Isandlwana.

David was an entomologist, among other things, so there’s an emphasis on the ‘small five thousand’ at the lodge, as well as the stock of plains game in the reserve. Fishing is big too, in the nearby Buffalo river. Accommodation is in two sections. The lodge is an original homestead and the guest house, also a former residence, is close by.

Both give the sense of guests being friends of the Rattrays, rather than on safari – an impression that follows through with the very personal, sociable service and home-from-home atmosphere.

Further afield, just west of Rorke’s Drift and Isandlwana, the Nambiti Big 5 Private Game Reserve near Ladysmith is home to both Esiweni Lodge and Nambiti Hills.

The reserve, brainchild of Rob le Sueur and Gordon Howard, came online in 2000. It is run privately by a board of the 12 lodge owners and limits the number of visitors. The experience is extremely personal. The malaria-free reserve is home to the big five.

The first thing that strikes most guests at Esiweni is the view. That initial step out onto the broad deck is breathtaking

The pick of the bunch is arguably Nambiti Hills, set atop a ridge for the best views. The feel is unashamedly classy, a combination of the best contemporary design with vintage safari touches.

Thatch predominates and the suites have expansive views, as does the huge public area, which is double volume and beautifully designed. Unlike the doorstep lodges near the battlefields, Nambiti Hills trades on wildlife first and then the war history, which means morning and afternoon game drives are de rigueur.

Trips to the fields are popular and well organised, but this is a lodge as much for pampering – there’s a superb spa – as for reliving history. Nambiti has also gone into partnership with Teremok Marine Lodge on the KwaZulu-Natal coast, offering a beach component to a stay with transfers included.

The first thing that strikes most guests at Esiweni is the view. The lodge is built overhanging a high cliff on the Sundays river and that initial step out onto the broad deck is breathtaking. It also focuses on wildlife and indulgence first, with a secondary, very decent programme for the Anglo-Zulu battlefields of 1879 and many preserved sites of the second Anglo-Boer War. There are only five suites in the lodge, all enormous, with views and balconies. Personal attention is the order of the day.

Back at Isandlwana, Andrew Rattray tells the story of how Fugitives’ Drifts’ new meeting venue, the hilltop Harford Library, was named. Typical of the Rattrays (and much of the history here) there’s a character involved.

Charlie Harford was an ardent entomologist, part of the Natal Native Contingent. In the midst of the terrors of war, Harford kept his focus downwards and stopped the skirmish at Sihayo’s Stronghold to retrieve a rare beetle so he could pickle it in gin.

It’s an apt example of how the battles were inevitably about people, and the Rattrays and Gerrards of the region bring them to life with conviction and wit. It’s a first-class holiday, past, present and pampering, all in one.

By Peter Frost

Images: Gallo/Getty Images, Fugitive’s Drift Media, Esweni Media, Nmbiti Hills Media