If you think you can beat a bear, king cobra or an eagle in an unarmed fight, safely land a plane without any training, or win a point in a tennis match against 23-times Grand Slam winner Serena Williams, you’re probably male. New research reveals that men (but typically not women) often display staggering confidence in their knowledge and abilities, even in a high-stakes environment.

‘Overconfidence is associated with gender,’ say researchers from Waikato University, New Zealand, who conducted a study in which two groups of people were asked how confident they were to make an emergency landing in a small plane. One group was shown a ‘useless’ video clip of a pilot landing a plane, which obstructed the hands and controls and didn’t teach anything. Yet the researchers found that those who had watched the video were more confident of landing the plane than those who hadn’t watched it; and that, overall, men were more confident than women.

‘This gender overconfidence gap is most prevalent when people are asked to evaluate their performance on a masculine gender-typed task. By contrast, women do not show the same overconfidence for feminine gender-typed tasks,’ say the researchers.

Their paper also mentions two UK YouGov surveys. In the first, 12% of men (but only 3% of women) claimed they could win a point against tennis champion Williams. The second asked which animals people thought they could overpower with their bare hands, and more men than women responded that they could beat any animal on a list that included bears, cobras, eagles, lions, wolves and gorillas.

Improbable as these scenarios may appear to be, the Waikato researchers suggest that over-confidence could be an advantage in business. They report that over-confident people are considered by others to be more knowledgeable and trustworthy than their equally competent (but not over-confident) peers, and are accordingly awarded higher status. These findings may indicate one of many reasons why women are under-represented in business careers, particularly in traditionally male industries and STEM (science, technology, engineering, maths) fields.

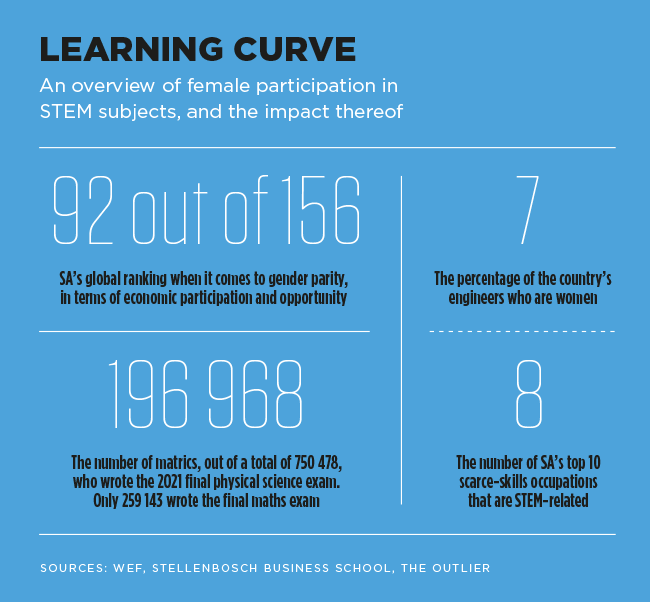

Women account for just 28% of graduates in engineering and 40% in computer science, according to the Unesco Science report 2021, which stresses the importance of these skills for the future. And while women make up just 22% of the AI workforce worldwide, SA is actually slightly ahead of the curve with 28% (on par with Singapore and Italy), and way ahead of nations such as Brazil (14% female participation in AI), and Germany and Poland (both only 16%).

The gender gap regarding (over) confidence appears to be a result of gender stereotyping and social expectations, rather than scientific evidence of differences between the ‘male’ and ‘female’ brain.

‘From a young age, most girls are taught to avoid risk and strive for perfection, while boys tend to be rewarded for being brave and taking chances,’ says Reshma Saujani, founder of Girls Who Code, an NPO that brings more women into computer science. ‘By the time they’re adults, whether they’re negotiating a raise or asking someone out on a date, they’re habituated to take risk after risk and rewarded for it.’

In her TED talk about the gendered ‘bravery deficit’, she mentions a study in which bright fifth-graders handled an assignment that was too difficult for them. The girls quickly gave up (in fact, the higher their IQ, the more likely they were to quit), while the boys found the difficult material energising and were more likely to redouble their efforts.

The difference lies in how boys and girls approach a challenge, says Saujani. To illustrate her point, she quotes a Hewlett-Packard report, which reveals that men in the organisation will apply for a job even if they meet just 60% of the qualifications, while women will apply only if they meet 100%. This perfectionism can prevent women from acting boldly, which limits their professional chances for success.

Encouraging girls and young women into STEM education and careers is gaining urgency, as women are in danger of being left behind economically. And, at the same time, SA needs ‘all hands on deck’ to address skills shortages and increase productivity.

Representation also matters for the future of the tech field itself, according to Gcobisa Ntshona, HR director of LexisNexis SA. ‘By excluding women from these spaces – spaces that are evolving and growing at a phenomenal pace – we run the risk of erasing their existence and lived experiences entirely. The only way to truly close the gap is to make the STEM space more accessible to women through shifts in gender biases and opportunities in education, funding and training.

‘From subtle discouragement in early education to limited opportunities and rampant sexism in the tech field, women are being left behind in the rush of digital innovation, and incremental changes just will not do it.’

A number of programmes aim to attract more girls into STEM fields, such as Techno Girl, the successful job-shadowing initiative for disadvantaged girls run by two SA government departments in partnership with Unicef. Then there are Mastercard’s Girls4Tech; the Motsepe Foundation’s Girls in STEM; and GirlCode, which offers free online coding classes for Grade 3 to Grade 12 girls and aims to empower 10 million women with tech skills by 2030.

Enel Green Power South Africa’s (EGP RSA) Back-to-School initiative is spearheaded by the business’ female employees in senior technical roles. It involves mentoring girls in high schools – specifically the employees’ alma maters – and advising them about the career opportunities available to them if they do well at STEM subjects. ‘The purpose of the Back-to-School initiative is to not only motivate girl children to take up STEM subjects, but to give them a glimpse into the types of careers they can pursue post-schooling,’ says Rebecca Letsoso, maintenance planner at EGP RSA, who mentors girls at Osizweni Secondary School in Secunda, which she once attended.

‘The initiative allows us to engage with the young learners and give them first-hand insight into the challenges and victories we – as women in renewables – experience.’

Teachers also play an important role in encouraging girls to study STEM subjects and sparking life-long interest in this field.

‘When you bring science alive, you motivate learners to find out more about the wonders of science,’ according to René Toerien, a physical science teacher who has taught at both girls’ and boys’ single-sex schools. ‘Motivation leads to achievement and opens up career options after school.’ A few years ago, she was involved in developing experimental science kits to help 5 000 school teachers make their subject more exciting. The lunchbox-sized kits, launched by UCT’s department of science and technology, focused on acids and bases, because that was an area where Grade 12s had performed poorly in past exams. To explain key science concepts, the kits contained simple experiments to ‘wow’ the learners.

‘The idea is to make the hidden magic of science visible and then sprinkle small bits of this magic throughout your teaching, as this goes a long way towards keeping girls – and boys – motivated,’ says Toerien. ‘Another way is to take learners to places where science happens, like a science centre, or where you can explore things, such as the aquarium.’

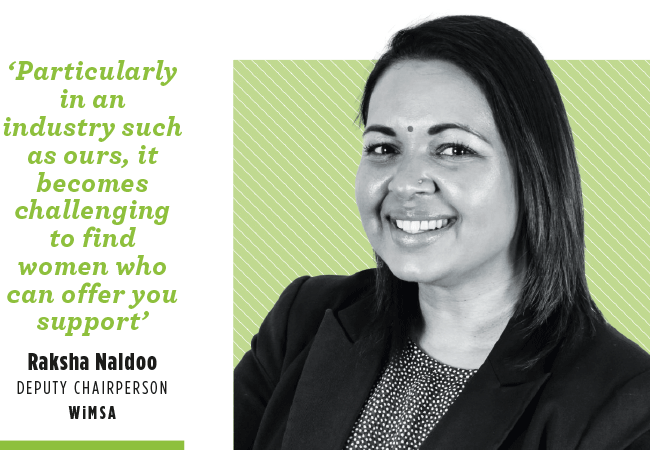

Sometimes STEM organisations come into schools to recruit female learners. Women in Mining SA (WiMSA), for example, participates in school job fairs and distributes career booklets to high school learners, explaining the variety of mining professions that don’t require underground work. By being exposed to these careers from Grade 8 onwards, the girls gain new perspectives and are able to choose school subjects accordingly. Deputy chair Raksha Naidoo explains that WiMSA is a community that helps women find their voices, learn through challenges, and take the steps forward to stand against bias and find their successes.

Mentorship of young women entering mining plays a vital role at WiMSA. ‘Particularly in an industry such as ours, it becomes challenging to find women who can offer you support; women who understand the challenges that you experience, and who can share guidance and experiences with us, so that we can learn and overcome and, ultimately, empower ourselves to be better,’ she says.

‘Our mentorship programme was launched in 2021 as an online peer-to-peer mentoring programme, aimed specifically at young graduates or women in the early stages of their career. Three sessions a month cover various topics necessary for mentorship, and take various forms of interaction and learning.’

Informal mentorship is also encouraged and supported, with various discussions, podcasts and networking sessions tackling this because, according to Naidoo, almost all conversations ultimately lead back to mentorship. As women progress in their careers, mentorship, coaching and networking remain important across all STEM industries in SA. Female chartered accountants can, for example, benefit from women-only masterclasses and the Women in Leadership conference held by the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants. On its website, the institute asks learners to rethink misconceptions of accountants (‘boring old men in grey suits’) and instead see them as the backbone of business, with ‘many of the most successful CEOs, CFOs, vice-presidents, chairmen and -women and finance managers’ being accountants.

When girls understand that the fields of accounting, engineering, scientific research and software development are theirs too, they should confidently enter STEM and male-dominated industries. ‘Companies have the power to change the gender balance, through decisions made about workplace diversity, which influence how appointments and promotions relating to women are made,’ says Lee-Ann Samuel, group executive: people at Implats. ‘But change doesn’t start when graduates enter the workplace – change starts when women are still at high school.

‘At Implats, we educate schoolgirls about opportunities in the mining industry. We walk alongside them through their university careers – providing necessary sponsorship, support and mentorship. Then, when they enter the workplace, we are deliberate in our actions in terms of mentorship, training and growth opportunities.’

Essentially, women have the ability to be just as good (or bad) as men, whether it’s in STEM careers, or performing an emergency plane landing and fighting king cobras.