Since as long as anybody can remember, the roads to Black Rock mine have been shrouded in total darkness at night. That’s no surprise: towns – and mines – don’t come much more isolated than Black Rock. Located in the middle of the great Northern Cape nowhere, just north of Hotazel, about 90 minutes south of the Botswana border, Black Rock sits atop one of SA’s largest manganese reserves.

To make pedestrians and motorists using the roads into the mine feel safer, LED lighting manufacturer BEKA Schréder was asked to provide a workable solution to illuminate the roads’ key intersections. The isolated location made a complete electrical reticulation too expensive, and so a solar street lighting solution – featuring solar-powered LED lume-midi luminaires, mounted 8m above road level – was installed.

In many ways, those roads outside Black Rock represent the challenges faced by mining companies as they move – some through choice; some through necessity – from traditional energy to more efficient solutions. Many of SA’s mining operations are located remotely and off the grid, in places where electricity is provided by heavy fuel oil or diesel gensets, which need to be bought, transported to the mine and maintained. Solutions like that simply aren’t sustainable, particularly not at a time when the industry is being forced to become ever slicker, leaner and more efficient.

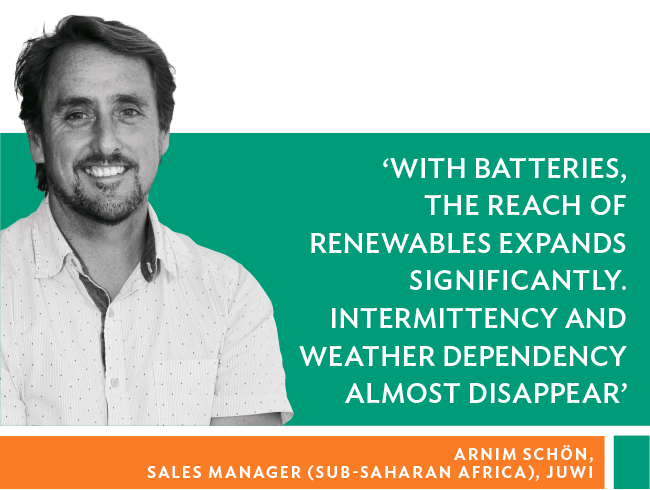

There are at least two drivers behind this. On the one hand is the business case. ‘In mining, the electricity costs are generally around 20% to 30% of the operational costs, so reducing power costs will obviously have a big impact on the bottom line of a mine,’ says Arnim Schön, sales manager (sub-Saharan Africa) at renewable energy company Juwi. Then there’s the environmental case, which boosts the mine’s social and environmental licence to trade. Anglo American chief executive Mark Cutifani summed this up at the launch of the company’s sustainability strategy in early 2018. ‘Our metals and minerals are the precious ingredients that enable and celebrate so many aspects of our modern lives,’ he said. ‘But our role in today’s world is far greater than simply as a supplier of physical products.

‘If Anglo American is to play its part in creating a sustainable future for the world and improving the lives of all of us who live here, then we must be prepared to challenge our business and ourselves, by re-imagining mining.’

Anglo American’s sustainability strategy is part of its FutureSmart Mining approach to sustainable mining, covering three major areas: the environment, community development and driving greater trust and transparency across the mining industry. The strategy includes specific goals that the company aims to achieve between now and 2030. ‘Delivering on these commitments will transform the way Anglo American does business,’ Cutifani added. ‘Keeping our people and the environment safe, supporting excellent education, and using our unique approach of collaborative regional development to further enhance our ability to provide truly sustainable benefits for our host communities present a different picture of the future of mining.’

Having laid out the environmental case, Cutifani presented the business case. ‘The financial benefits to our business by 2030 are expected to be significant, including from substantially reduced energy and water costs,’ he said. ‘At the same time, we expect our innovative approach and the technologies we are developing to open up new mineral resource opportunities for us over the medium term.’There’s also a tax incentive. In late 2017, listed gold producer Harmony Gold received a tax incentive for the energy savings it achieved on the compressors at its Tshepong gold mine in the Free State.

Section 12L of the Income Tax Act was introduced mainly to encourage businesses to implement energy efficiency measures that contribute towards reductions in greenhouse gases. It provides a tax allowance of R0.95 (originally R0.45) per kWh hour saved over a continuous period of 12 months. In this particular case, Harmony’s saving was the tax it would have paid on income of R5.7 million.

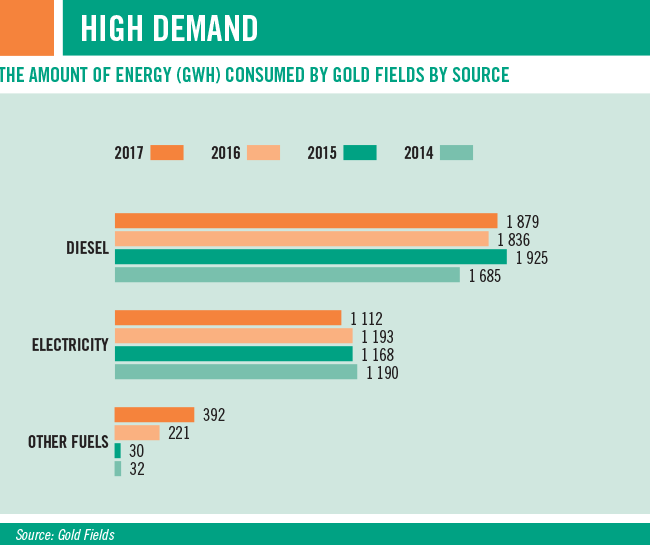

In the past, many mines were reluctant to consider pure renewable solutions, which relied on daylight (for solar power) and co-operative weather conditions (for solar and wind). As a rule, mines are ‘always on’ – operating all day, every day, all year round. Starting up or shutting down a mine is a complex process that can take several precious hours, and any interruptions to the energy supply can hurt the bottom line and be dangerous to the people working in the mine.

Hybrid power – which allows mines to run renewables when the sun shines (solar) and the wind blows (wind), with diesel or battery power back-up when required – is fast emerging as a more attractive, best-of-both-worlds solution. This is particularly true as battery power becomes cheaper, allowing mines to shift seamlessly and efficiently from renewable energy to diesel power, and back again. The cost of renewable is now more or less the same as grid-supplied electricity. ‘What we’re able to do is put a renewable/ hybrid solution behind the grid at equal or less cost, with added reliability and consistency in supply,’ says Schön. ‘In many instances renewable energy is significantly cheaper than grid supply, so we’re able to offer a cheaper and more reliable solution compared to the grid.’ Juwi can now design hybrid plants that produce electricity below $0.10 per kWh in many locations in Africa. ‘I believe this is very attractive for many mines,’ he says, adding that in many sub-Saharan African countries, grid costs are still fairly high. ‘So even $0.10 would be attractive to many operations.’

Listed miner Gold Fields has previously underlined its commitment to using renewables for at least 20% of the total life-of-mine power requirements in new projects. In line with this, the company recently introduced hybrid technology as part of its move towards renewables. In mid-2018, two years after it replaced the diesel power station at its Granny Smith gold mine in Western Australia with a 21 MW gas-fuelled reciprocating engine station, Gold Fields announced plans to integrate a 7.3 MW solar and 2 MW battery system into that gas supply.‘The integration of renewables at Granny Smith mine is a demonstration of Gold Fields’ ongoing commitment to both environmental sustainability and innovation at its operations,’ says Stuart Mathews, executive vice-president (Australasia) at Gold Fields. ‘These proposed new measures are intended to reduce our carbon footprint by utilising the latest hybrid energy technologies.’

The new hybrid power station, combined with a thermal station expansion, will meet the mine’s 24.2 MW daily power needs. Aggreko, the company contracted by Gold Fields to install the hybrid system, highlighted the cost-saving aspect of the deal. ‘We recently announced the availability of microgrids-as-a-service for customers who want to leverage the benefits of hybrid energy solutions while minimising capital outlay,’ says Aggreko MD Karim Wazni. ‘This system will be the first time Aggreko incorporates battery storage into a hybrid power system, and – significantly – it’s a rental, which underscores the value and appeal of this new model.’

Ultimately, energy-efficient solutions will enable miners to work safely and cost-effectively, with a reliable, uninterrupted power supply. And, as highlighted by those solar street lights leading into the Black Rock manganese mine, those same solutions will enable mines to improve conditions for their neighbours and broader communities.

‘Another advantage of combining renewable energy and battery storage with a grid or fossil fuel power source is the ability to stabilise the grid,’ says Schön. ‘With batteries, the reach of renewables expands significantly. Intermittency and weather dependency almost disappear. This means cheaper, more reliable and cleaner power for off-takers.’