Our articles about cybersecurity usually start by providing SA’s latest ranking in global cybercrime activities. We’ll get to that in the next paragraph, but first – as the country’s cybercrime rates continue to climb – it’s worth providing a ranking of a different kind. According to Alexa’s country statistics, SA’s 14th, 23rd and 44th most popular websites are illegal file-sharing sites (YTS, Pirate Bay and 1337x, respectively). When you consider that the rest of the top 40 include household names such as Google, YouTube, Facebook, Wikipedia and Takealot, you know you’re dealing with a lot of traffic. And when you then notice that the 34th most-visited site is Bodelen, a malicious redirect site that you only go to if you’re sent there by a computer virus, the full picture of SA’s cybercrime problem becomes a lot clearer.

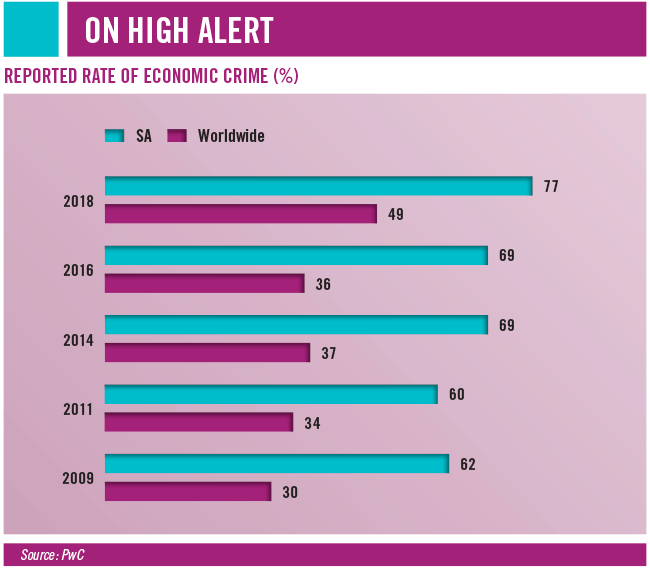

According to PwC’s 2018 Global Economic Crime and Fraud survey, SA ranked first in the world for economic crime, which includes theft, consumer fraud and, of course, cybercrime. Indeed, 29% of SA survey respondents said they had experienced cybercrime in 2018, while 26% believed cybercrime will be the most disruptive economic crime to affect their organisations in the next 24 months.

This is a massive challenge for businesses, due to a crippling combination of business disruption, financial impact, limited resources and the increasing frequency of attacks. Small enterprises are particularly at risk.

According to Jenny Jooste, professional indemnity and cyber underwriter at Chubb Insurance South Africa: ‘Our claims data and global research is showing that cyberattacks directed at SMEs are steadily increasing. As a group, SMEs tend to devote inadequate resources, time and funds to cybersecurity, with fewer than 3% of all SMEs having cyber insurance. Criminals target these companies because their IT controls are not as sophisticated as large corporate companies, and the skills for dealing with these threats are often not specialised, making them perfect targets.’

That’s why schools and universities are also such soft – and popular – targets. In 2016, the University of Limpopo’s website was taken down in a cyberattack that saw exam papers being leaked, the university’s intranet being compromised, and the personal information of more than 18 000 students published online. ‘In Aon’s 2018 global risk management survey, cyber risk was ranked as the number one risk facing educational institutions and is likely to remain so for the foreseeable future,’ according to Kerry Curtin, cyber-risk expert at Aon South Africa. ‘The need to strengthen institutional resiliency against potential damage, compromising hacks and downtime is crucial.’

Jooste agrees that cybercriminals usually look for targets that can be easily hacked. ‘They often accomplish this by using software that automatically scans the web and identifies businesses with specific security weaknesses, such as outdated or unpatched software, poor password hygiene, open web ports, unencrypted data in transit, lacking endpoint protection and the like,’ she says. ‘They can also gain entry through a server room break-in or from internal network hacking, which then enables monitoring by criminal third parties. This can often be triggered by something as innocuous as plugging an infected USB drive into a computer or device that is connected to an internal network.’

The consequences of a cyberattack can be serious – and unexpected. Business owners and company directors, for example, can be held personally liable for their fiduciary duties if the necessary cybersecurity measures and policies aren’t put in place. ‘Claiming ignorance about cyber risks is no longer an excuse,’ says Jooste. ‘Proactive steps must take centre stage to mitigate and prepare for potential cyberthreats, no matter the size of your business.’

Meanwhile, the South African Banking Risk Information Centre (SABRIC)’s Digital Banking Crime Statistics report, released in late 2018, notes that in 2017, nearly 13 500 incidents across banking apps, online banking and mobile banking cost the industry more than R250 million in gross losses, and incidents from January to August 2018 showed a 64% increase. Speaking at the launch of the report, SABRIC CEO Kalyani Pillay emphasised that social engineering attacks are the biggest threat to South Africans. Criminals know that banks have high levels of cybersecurity, so they target individuals instead using low-tech traps such as bogus emails. ‘Criminals are using their social engineering tactics to manipulate people into providing them with the information they require to commit the crime,’ says Pillay.

The trouble is, the effects of cybercrime are seldom limited to the individual target. Karen Renaud, professor of cybersecurity at Abertay University in Dundee, Scotland, highlights this in a recent column for the Conversation. ‘The cybersecurity risk is currently managed by governments in the same way as they treat private smoking – as if it were a solo risk,’ she writes.

‘By and large, governments provide advice about cybersecurity risks and then leave citizens to either take security precautions – or not. This seems to be based on the assumption that only the individual computer or device owner suffers loss or harm if they fall victim.’

In reality, she writes, cybersecurity attacks are like fire and disease: they seldom affect just one individual. ‘Data stolen from one person’s device is likely to include the personal details of many other people, potentially endangering the wider community. Malware and viruses also spread from one person’s device to another.’ That last point is precisely why cybercriminals target individuals: they’re an obvious weak point in their company’s otherwise-reliable cybersecurity protection.

‘This is going to be an ongoing battle for a while still, especially with the increase in insecure IOT devices now flooding the market,’ says Nadia Veeran-Patel, cyber resilience manager at ContinuitySA. ‘There is little to no government regulation – worldwide – enforced to force the manufacturing of secure devices, and this leaves the user to ensure that the device is secure after installation. All one needs to connect and control these devices is a mobile phone.’

She adds that more awareness needs to be ingrained around where, what and how to connect safely – whether it’s to gain access at work or in the home. ‘Organisations should look into restricting access to USB ports as many people not only plug in thumb drives but their phones as well to do data transfers,’ she says. ‘The least-realised and reported-on threat is still the insider. Whether malicious or not, they are and always will be your strongest and weakest links.’ Besides, those companies’ cybersecurity is probably nowhere near as reliable as they would like to think.

A new report by Kaspersky Lab finds that, while many SMEs are achieving great efficiencies by using applications to help manage projects, sales and customer service operations – and this is despite a lack of resources and funding – most SMEs are fooling themselves when it comes to the quality of their cybersecurity measures. Almost half (42%) of the SMEs surveyed by Kaspersky Lab experienced at least one data breach in 2017, even though the majority (72%) were sure they were reliably protected from such incidents.

‘Digital transformation gives small and medium-sized companies new opportunities for growth,’ says Kaspersky Lab’s head of B2B product marketing, Sergey Martsynkyan. ‘Collaboration services and other digital applications can have a huge impact on efficiencies and long-term business success. But to ensure they are not adding a layer of vulnerability and risk into the organisation, it is vital to think about their security and that of the data they hold. As IT infrastructures become more complex, businesses can lose control over their data. To prevent growing organisations from falling victim to accidental breaches or planned attacks, IT security needs to become just as much a key to success as financial, legal and personnel considerations.’

As technology develops, becoming increasingly central to the success of businesses of all sizes, cyberattacks will only become more frequent, more sophisticated and more damaging. The Official Annual Cybercrime report from Cybersecurity Ventures estimates that by 2021, global cybercrime will cost $6 trillion annually – making it more profitable than the global trade of illegal drugs.

As things stand, SA’s legal framework relating to cybercrime is a hybrid of different pieces of legislation and common law. To keep up – and catch up – with developing technology, National Assembly passed the Cybercrimes Bill in November 2018. One of the legal measures in the new bill places an obligation on electronic communications service providers to report offences related to copyright infringement – in effect, internet piracy.

While the proposed bill has been criticised and praised in more or less equal measure, the inclusion of internet piracy may well be a good thing for SA businesses, if albeit in a roundabout way. The growing trend for employees to work from home and or to ‘bring your own device’ has blurred the lines between the business’ tech and the individual’s tech. If a personal laptop, hard drive, flash drive or mobile device were to be compromised, that could pose a serious threat to the business.

‘Depending on the type of breach, appropriate government or regulatory offices may need to be informed of the breach to anticipate possible legislative or regulatory fines,’ says Curtin, adding that while some existing forms of insurance might carry a level of coverage, only specialist insurance policies – which very few SMEs could afford or would even think to consider – provide the extensive cover needed for a cyber breach.

Ordinary South Africans don’t notice that their computer slows down slightly whenever they visit Pirate Bay to download the latest pirated episode of Game of Thrones. The reason is because the site automatically uses browsers’ CPUs to mine cryptocurrency. Very few BitTorrent downloaders realise this. What other gaps have they left in their personal cybersecurity armour, and how could that carelessness affect their or their employer’s business?