Nelson Mandela’s first trip abroad, outside Africa, after his release from Victor Verster prison in February 1990, was to Sweden. This was no coincidence. Speaking to the Swedish parliament, only days after he had become a free man, Mandela was fulsome in his praise for the support Sweden had given to the anti-apartheid struggle and the African National Congress in particular.

Sweden’s current ambassador to SA, Håkon Juholt, points out that Sweden was the single-largest donor, alongside the Soviet Union, to the anti-apartheid cause. But unlike the Soviets, who supplied mostly weaponry and armed training, Swedish aid was not intended for military purposes.

‘A fundamental, indeed sacred, criterion was that Swedish support had to be humanitarian,’ says Juholt. Starting in 1969, Sweden donated a total of about $400 million to the anti-apartheid cause.

Yet Sweden’s support for the struggle came at the expense of trade and business relationships. Juholt says that in 1948, the year apartheid was formalised, SA was Sweden’s third-largest export market outside Europe, accounting for 2.3% of trade. Sanctions progressively tightened from 1979 onwards, culminating in a total embargo in 1987.

‘Trade between Sweden and South Africa plummeted from $150 million in 1984 to $41 million in 1988,’ says Juholt. With the end of formal apartheid and the resumption of diplomatic links in 1993, ‘the relationship had to be transformed’, he adds.

The reformatted relationship took the form of a ‘finite period’ of official development aid, terminating in 2013, although some assistance continues, especially in the area of sexual and reproductive rights. In parallel with the surge in aid came a resumption of trade and business relationships.

‘Sweden’s relationship with South Africa in the post-apartheid period has followed the classic aid-to-trade trajectory,’ says Rupa Thakrar Bagoon, trade commissioner and SA country manager at Business Sweden.

She points out that there has been a surge in Swedish engagement with SA since the end of formal apartheid. Today there are 80 Swedish subsidiaries and more than 450 Swedish brands represented in SA.

Sweden has a particularly strong manufacturing sector that accounts for roughly 20% of the country’s GDP. Much of this revolves around ‘advanced manufacturing’, with Sweden being a global leader in the design and application of digital technologies to manufacturing, processing and logistics.

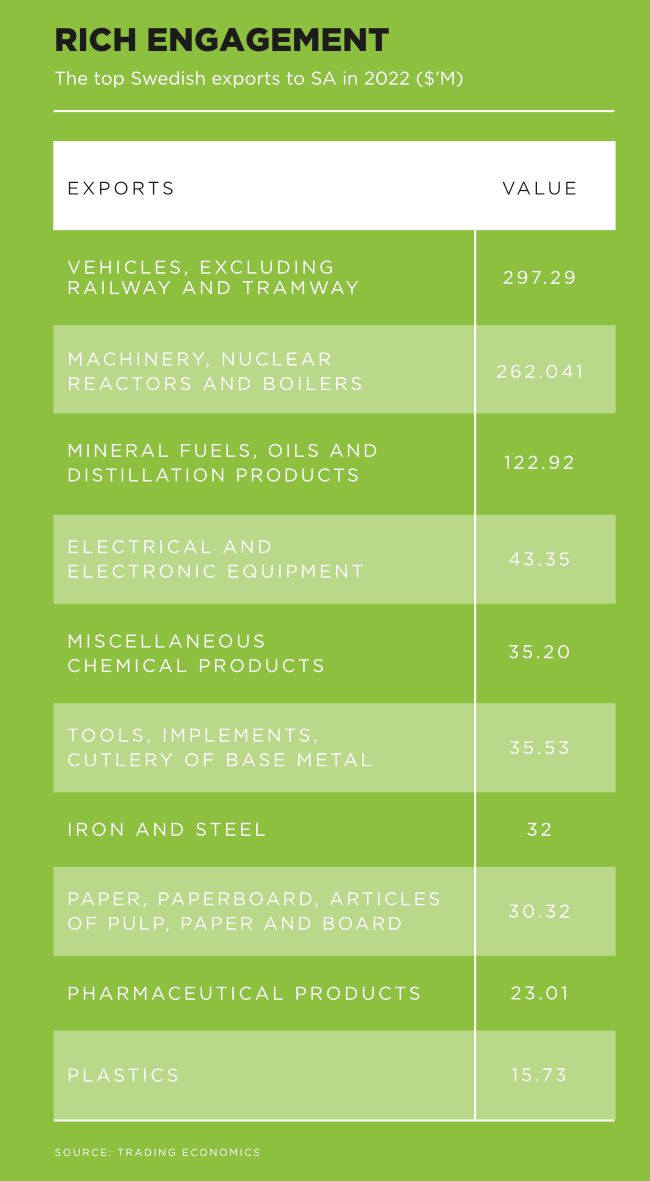

Its exports to SA were valued at just less than $1 billion dollars in 2022. This is not a particularly large figure in the bigger scheme of SA trade, but two features stand out. First, Swedish exports to SA are 10 times greater than those from Sweden’s Nordic neighbours, Norway and Denmark, and approximately twice that of the other industrialised Scandinavian economy, Finland.

Second, Sweden’s exports to SA are almost all manufactured goods, dominated by heavy vehicles and machinery. By contrast, SA’s exports into the Swedish market, valued at $142 million in 2022, are predominantly beverages and fresh fruit.

It’s not surprising that Sweden’s leading companies are well represented in SA’s technology, manufacturing and logistics sectors. Companies with a strong presence include Ericsson, which has developed from a mobile handset manufacturer to a much more niched network technology provider. The company was selected by SA-based mobile telecoms giant MTN as its primary 5G network upgrade partner in 2019.

Both Swedish heavy transport manufacturers, Volvo and Scania, are well represented in SA’s trucking market. This is a thriving sector, given SA’s shift away from rail to road haulage – thanks to problems at state-owned rail operator Transnet.

The market for medium and heavy trucks in SA is booming. According to the National Associations of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa, in mid-2023, about 1 700 heavy trucks were being sold every month, more than 20 000 per year.

In a competitive market, Volvo was ranked fifth in July 2023 (283 units sold) and Scania seventh (251 units sold). Heavy trucks are not manufactured in SA. What Volvo and Scania offer is proven high-end technology and after-sales service. Both have introduced heavy electric trucks in SA on an experimental basis.

‘We are in the early stages of our electric truck journey here in South Africa,’ according to Waldemar Christensen, MD of Volvo Trucks South Africa. ‘There are, of course, infrastructural and legislative obstacles to overcome, but we are preparing for the future.’ Volvo Trucks is the market leader in Europe, with a 32% share of the market for heavy electric trucks, and in North America, with nearly half the market in 2022.

Sweden’s return to the SA market has seen significant investments in the manufacturing sector. Companies with a presence include defence manufacturer SAAB, which entered the SA market in the late 1990s. It jointly owns SAAB-Grintek, an advanced avionics manufacturer. The company, which has been named South African Exporter of the Year at least three times, makes and sells an electronic warfare self-protection system that is used by air forces in 15 countries, including India. Last year, it was awarded the contract to rehabilitate and maintain the South African Air Force’s fleet of Gripen air-superiority and strike fighters.

The mining sector has also attracted Swedish interest. The stand-out investor here is mining equipment manufacturer Sandvik. The company opened a new manufacturing facility in Kempton Park last year at a cost of R350 million. It has 550 employees and is designed to be a regional office, supplying the mining industry throughout sub-Saharan Africa. Sandvik’s best-known local product is a low-profile loader, used especially in underground mines where access is an issue.

‘The commercial relationship between Sweden and SA does not start and end with companies,’ argues Bagoon, referring to a range of Team Sweden institutions, such as Business Sweden, Swedish embassies, Swedfund, the International Council of Swedish Industry, Swedish International Development Co-operation Agency, Swedish Export Credit Corporation and Swedish Export Credit Agency, to name a few.

According to President Cyril Ramaphosa, speaking at the opening of the Sandvik facility last year, the investment was discussed at the ninth session of the SA-Sweden Binational Commission, held in Stockholm in 2015. The commission is simply the apex of a vast range of interactions between Swedish and SA institutions, including academic exchanges, city twinning and trade agreements.

These are rooted in what Juholt describes as ‘our shared common values’ and a history of ‘international solidarity and activism in the fight for freedom’.

According to SA’s Department of International Relations and Co-operation, there are some 20 bilateral trade agreements between the two countries.

Swedish officials frequently comment on a ‘distinctive Swedish way’ of doing business. It’s extremely co-operative (between management and labour), places a premium on continuously improving workers skills and, in many respects, reflects the acclaimed Nordic model, which combines market-friendly economics with extensive social welfare provisions.

In SA, this translates into a concern with training and empowerment. Sandvik, for example, has a virtual training facility and simulator at its Kempton Park facility.

Looking ahead, it is likely that Sweden’s industrial economy has much to contribute to SA society in this respect, especially if SA becomes more surely placed on a low-carbon transition. The existing well-established relationship – with its dense layers of personal and institutional engagements – can be expected to work to the mutual benefit of both countries.