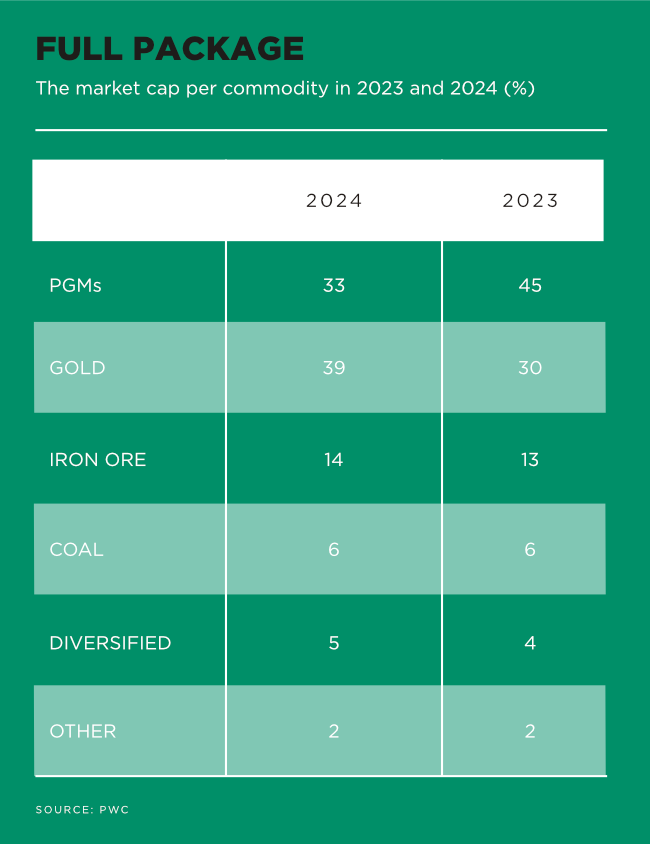

With the exception of the gold price, which reached record highs, mineral prices tended to be flat or lower in 2024. Around the world, the share prices of the five big diversified international miners (BHP, Rio Tinto, Vale, Glencore and Anglo American) fell by double-figure percentages in the first half of the year. But this was no obstacle to activity in the JSE general mining segment. Mining, worldwide, experienced a surge in M&A activity and the JSE was at the centre of one of the biggest M&A events of the year.

‘Companies have had to look beyond mining to survive the downturn. This past year, we observed that what was front of mind for many companies was safeguarding their balance sheets to survive the down cycle and to position them for opportunistic prospects,’ says PwC Africa energy, utilities and resources leader Andries Rossouw.

‘To spot those opportunities, you need to be following commodity prices,’ he adds. ‘Copper, with its green economy applications, is currently the bet of choice globally. Exploration spending in the copper space has been the highest of all commodities, except for gold, for the past decade or more.’

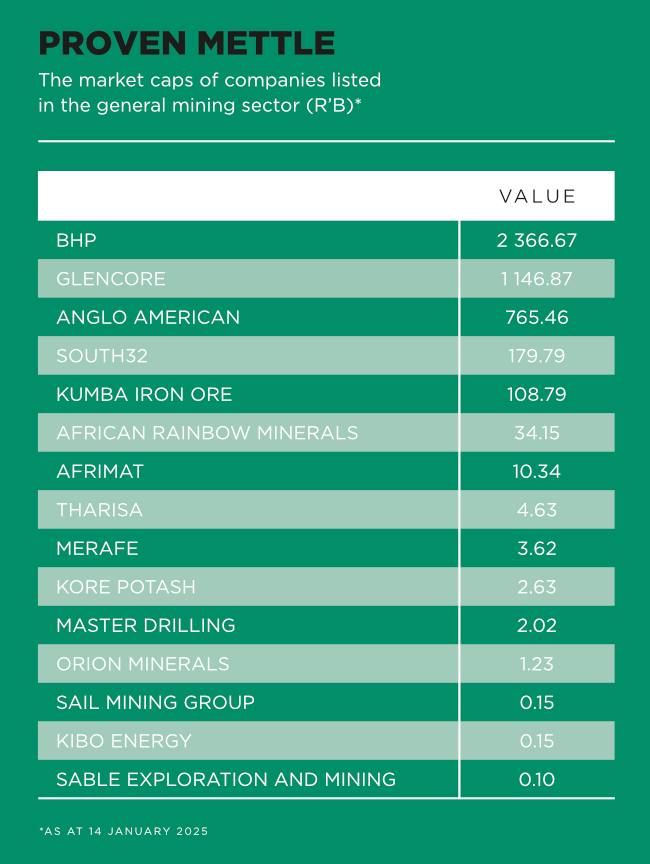

In April, Melbourne-based global iron and coal miner BHP approached Anglo American with an unsolicited bid of $39 billion. BHP, listed on the Australian Securities Exchange with a secondary listing on the JSE, is the world’s largest mining company by market cap. Despite its JSE listing, BHP currently owns no assets in SA.

Anglo American, a household name in SA with a century-long history, shifted its primary listing to London in 2019, maintaining a secondary listing in Johannesburg where it was founded. It is the world’s 10th-largest diversified miner and the proposed take-over would have been the biggest mining deal for many years.

Anglo still owns high-quality SA assets in the form of Kumba Iron Ore and Anglo American Platinum (Amplats), both listed separately on the JSE. But neither of these commodities performed well in 2024. The iron ore price hit a two-year low in September on the back of lower levels of demand from China. Kumba also faced logistical issues as a result of the faltering capacity of the parastatal Transnet and was forced to reduce production in the third quarter.

Platinum group metals (PGMs) – used mostly as an exhaust catalyst for internal combustion engines – face a long-term threat in the emergence and rise of electric vehicles.

‘The energy transition has shifted mineral prices in interesting directions. While copper is the one sure bet, other impacts are evident too. Uranium, for instance, climbed over 200% in 2024, on the expectation of a return to nuclear power,’ says Rossouw. But not all transition minerals have benefited. Lithium prices fell 30% in 2024 on oversupply issues.

Analysts are clear that BHP’s bid was mostly about getting its hands on Anglo’s copper assets. Anglo’s share price had fallen 10% in 2023, leaving it vulnerable. Anglo American owns four healthy copper mines in Latin America, with the newest Quellaveco in Peru, having begun producing only in 2022. It is one of the most modern and automated mines in the world, powered entirely by renewable energy. BHP, which has described its outlook as ‘bullish’ on copper, already owns the world’s largest copper mine, Escondida in Chile.

Anglo’s board rejected BHP’s repeated offers three times in April and May. The last offer was worth $10 billion more than the original approach ($49.18 billion).

Anglo chairperson Stuart Chambers described BHP’s behaviour as ‘opportunistic’ and told shareholders at the company’s AGM that ‘it failed to [adequately] value the company’s [future] prospects’. He added that the bid was ‘way too low for us to be able to recommend to our shareholders that they consider or accept it’.

Furthermore, BHP had made its offer conditional on Anglo breaking up the group and demerging or selling especially its SA platinum and iron ore assets as well as other structural changes. But Anglo already had its own restructuring programme under way. This involves the listing of Amplats in London and divesting from global diamond mining giant De Beers, as well as the sale of metallurgical coal assets in Australia.

The metallurgical coal deal was announced in early December with the sale of five mines in Queensland to Peabody Energy, a US coal miner. This puts Anglo American well on the road to the envisaged new structure, focused on copper, high-quality iron ore and crop nutrients (potash).

When Anglo turned down BHP’s third offer, the rejection triggered a regulatory mechanism that imposed a six-month moratorium on the process. BHP has made ambiguous noises about the prospect of resuming its bid. However, there has been speculation about other diversified international majors climbing on the bandwagon.

One possibility mooted is a bid for Anglo from Swiss-headquartered Glencore, another company with a primary listing in London and a secondary listing on the JSE. Unlike BHP, Glencore currently owns substantial assets in SA. It has coal operations in Mpumalanga, the Astron refinery in Cape Town (and distribution network), as well as a chrome joint venture with JSE-listed Merafe Resources. Merafe operates two ferrochrome smelters, which means that the company’s success is heavily influenced by energy security issues.

Yet Glencore’s flat performance in 2024 was typical of the general mining segment. ‘Against the backdrop of lower average prices for many of our key commodities during the period, particularly thermal coal, our overall group adjusted EBITDA of $6.3 billion was 33% below the comparable prior year period,’ said Glencore CEO Gary Nagle at the company’s half-year results report in August.

There are other copper plays in SA, although only one – Orion Minerals – is listed in the general mining segment of the JSE. Copper 360 is on the AltX Board while SA’s most established copper miner, Palabora Mine in Limpopo, is not listed.

Orion Minerals, incorporated in Australia and with a primary listing on the ASX, owns two copper assets in SA. The jewel in the crown is the Prieska copper and zinc mine, a long-established operation that was shuttered in 1991.

Orion is bringing it back into production and expects the first sales in 2025. Orion is also working to bring SA’s first-discovered deposit, Okiep copper, back into production.

Despite its Australian origins, Orion is heavily South African in focus. In 2024 it raised an initial R44 million, mostly from SA retail investors, for the further development of its local assets. The fundraising drive, facilitated by investor marketing agency Utshalo, expects to net about R150 million in total. It represents a deliberate attempt to source working capital for small mining development companies in a manner that has become more familiar in Toronto and Sydney.

Another diversified but more local player, African Rainbow Minerals (ARM), has also endured a torrid year. The company’s share price fell more than 12% in 2024. Originally an operator of marginal gold shafts, ARM is now active in the platinum, manganese, iron ore, nickel and coal sub sectors. None of these minerals has enjoyed supportive prices this year, while logistics woes (Transnet) have affected several of them. The company bought Bokoni mine at the top of the platinum price cycle (in 2022) and has paid the price subsequently. In 2024, it announced that expansion plans had been placed on hold.

South32 is another diversified company dual listed on the ASX and JSE. But the non-precious commodities miner, spun out of BHP in 2017, owns only two manganese mines in SA (Wessels and Mamatwan). Its most valuable assets in the region are the large aluminium smelters in Richards Bay and Maputo. While Southern Africa’s electricity cost advantage –relevant when the smelters were founded – no longer applies, South32’s operation is secure for the next five years. It has an electricity supply agreement with Eskom until 2031.

The rest of the general mining segment shows pockets of resilience in the face of the industries challenges. Master Drilling, the specialist high-tech drilling services and tunnelling company, is now an international firm that is based in Johannesburg. It did see business drop off in 2024 but it’s main issue recently was the impairment (writing off) of the $7.8 million specialised tunnel borer it had developed and built. But this is a one-off hit of R1.7 billion company with a turnover of $127 million in the past year.

Afrimat, which starting life as a building materials producer, has widened its operations to include coal and iron ore. This is an example of a company that has become excellent at what it does and is thus able to expand its operations into other areas. In 2024 it acquired Lafarge Cement from the Holcim group for $6 million plus responsibility for the company’s R900 million debt. This appears to be a big bet on future infrastructure growth.

Tharisa is a specialist in non-energy minerals, especially PGMs and chrome concentrates. Its low-cost open-pit operations in the Bushveld complex have allowed it to navigate the unimpressive performance of PGM prices in 2024, while its chrome production – with its stainless steel applications – positions it to benefit from China’s transition to a more consumer-intensive economy.

Sail Mining Group is a chrome miner and trader that owns two underground mines and an open-pit prospect in SA.

The second mine, Rooderand, was acquired with a 90% stake in its previous owner, Chrometco, in 2024. The company is also looking to expanded chrome utilisation in China and says it currently exports 1 million tons a year to that country.

The remaining three companies in the general mining segment are all involved in exploration and development.

Kore Potash is developing the Kola potash deposit in the DRC, Kibo Energy is involved in coal assets in Tanzania, and Sable Exploration and Mining is developing a magnetite asset with two partners.

Mineral prices in 2024 are a reflection of geopolitical uncertainties and the global technological transition to greener energy. The sideways or downward movement of commodity prices had inevitable impacts on the listed mining sector.

As Rossouw notes, the down cycle is a time to preserve balance sheets and position companies for future growth. A downturn is never a good time for investors but on the general mining segment of the JSE it has also not been an inactive time.