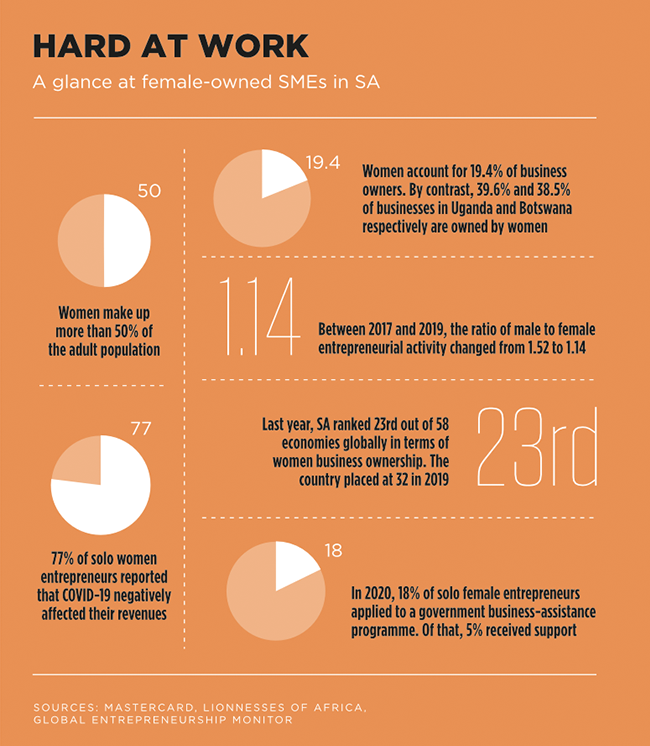

It’s still a man’s world, according to the latest Global Entrepreneurship Monitor South Africa (GEM SA) report. It confirms that while female entrepreneurship appears to be on the rise, women still face far greater difficulties in becoming entrepreneurs than men. The ratio of male to female entrepreneurial activity in SA has improved from 1.52 (12.5 male/8.2 female) in 2017 to 1.14 (10.9/9.6) in 2019, according to the report, which was published in 2020 by the University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB) and the Small Enterprise Development Agency. However, these figures pre-date COVID-19 and the full extent of the pandemic’s impact, especially on women-led SMEs, still needs to be evaluated.

‘Unfortunately many of the positive gains for women entrepreneurs have been eroded as a result of the pandemic,’ says Donna Rachelson, a branding and marketing specialist who is also a director of the Seed Academy, where a fully funded, three-month business accelerator for women entrepreneurs (AccelerateHer) was created. ‘Women play a key role in running households and caring for children and numerous research studies confirm that many women have either forfeited or lost jobs due to COVID,’ she says. ‘Entrepreneurs are suffering terribly at this time and being a woman entrepreneur is that much more challenging.’

In fact, 87% of female business owners worldwide felt adversely affected by the pandemic, according to the Mastercard Index of Women Entrepreneurs, which covers 58 economies. It also revealed that in SA, 59% of women-owned businesses were in sectors that were hardest hit economically, such as retail, restaurants and domestic services.

Yet SA’s economic recovery relies on the success of all businesses, right down to informal, women-owned micro enterprises. ‘Women’s entrepreneurship is recognised as the biggest, yet under-utilised, opportunity for sustained economic growth and social development,’ says the UN Economic Commission for Africa. It’s a view shared by Kgalaletso Tlhoaele, Absa Group head of enterprise development, who says that ‘women entrepreneurs in developing countries have proven to make business decisions that strike a balance between the interest of the entity and provide societal impact’. And in figures, this means that if women entrepreneurs achieved their full potential, the global economy would grow by $2.5 trillion to $5 trillion, boosting the global GDP by 3% to 6%, according to Boston Consulting Group (BCG). It also notes that for every dollar of funding, start-ups founded or co-founded by women generate $0.78 compared to $0.31 generated by male-founded start-ups.

Despite delivering these significantly higher returns, women typically find it more difficult than men to attract funding. This may be due to men making bolder projections and assumptions when pitching for funding, suggests BCG. In its report on why women-owned start-ups are a ‘better bet’, the group notes that, ‘one investor told us, “men often overpitch and oversell”. Women, by contrast, are generally more conservative in their projections and may simply be asking for less than men’.

This doesn’t only apply to start-ups but also to established businesses in need of finance. ‘We can see a trend that female-owned SMEs are much more cautious when applying for and requesting funding, mostly for significant projects in the pipeline or to service their growing business,’ says Cuan Hopley, CFO of Bizcash, a Sandton-based fintech firm that provides online finance and cashflow solutions to SMEs. ‘We see a higher approval rate – 54% – of women over men in the same situation, because we do not discriminate the loan process based on a demographic. ‘It’s our intention to remove the barriers women face when they apply to other financial institutions, therefore we measure each application on [its] own merit, using the same credit checks and risk analysis to remove any pre-conceived bias based on a subjective feeling.’ And Bizcash has noticed another trend – female SME owners tend to save their profits for future expansion and rainy days. So, statistically, they should find it easier to attract financiers than their male counterparts.

Absa too has noted a higher percentage of success with women-owned and -managed start-ups. ‘We have also observed better financial management of enterprises where women are looking after the finance or CFO function,’ says Tlhoaele. ‘Women are typically more prudent in managing an entity’s finances and the creation of sustainable value.’

According to Rayna Dolphin, executive director at Business Partners Limited, which offers financial and non-financial support to SMEs while setting its investment teams specific targets for supporting female-owned businesses, ‘it is our experience, as well as that of a number of other financial institutions, that female business owners are more likely to maintain good credit with lenders and, ultimately, be lower-risk lenders in our portfolio’. She adds that the company aims to increase these targets every year.

‘Female entrepreneurship is particularly important within the South African context where unemployment is at a record high. We have seen an increasing trend where females are becoming key players in previously male-dominated industries such as construction, engineering and manufacturing among others.’

This ties in with the recent government policy to source at least 40% of public procurement from women-owned businesses. While this is only mandatory for state-owned entities, the private sector has been asked to voluntarily also aim for this target.

Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, Minister in the Presidency for Women, Youth and Persons with Disabilities, indicated during Women’s Month 2021 that she would like to see more women-owned SMEs in manufacturing, mining and mineral exploration, as well as the green economy. Her department will air a series of radio shows on 11 of SA’s largest stations ‘to answer the questions women business owners have, but cannot get answers to, in all African languages’. These shows will, for example, explain how to register a business and how to do business with the state.

While government-led gender initiatives and policies are crucial in advancing women-owned businesses, Rachelson underlines that corporates also play a fundamental role. In addition to their allocating procurement quotas for female-owned SMEs, she advises companies to ensure that women entrepreneurs get the necessary funding support they require. Companies should also facilitate introductions and ensure that networks are opened to women with a strong focus on access to market. Furthermore, they should give women entrepreneurs access to commercial and business acumen in their operations.

‘Corporates should also nominate sponsors for women entrepreneurs from leading talent in the organisation,’ says Rachelson. ‘Sponsorship is a key component to advancing women in corporate environments, and it would be game changing to take the principles and power of sponsorship and apply these to women entrepreneurs. This would contribute hugely to taking them to the next level.’

In SA, women unfortunately often resort to ‘necessity entrepreneurship’ rather than ‘opportunistic entrepreneurship’, mainly to survive, without having the business knowledge or managerial competencies to run a successful enterprise, says Christine Chichi Kere, a leader development coach and organisation development consultant, whose paper on unleashing black women’s entrepreneurial power was published in the USB Women’s Report 2020.

‘The mindset of entrepreneurship as a career has yet to be embraced and promoted in South Africa,’ says Kere. ‘It’s often not celebrated as a viable career but as a back-up plan in case of unemployment, particularly for and by women and youths, who face the highest unemployment in the country.’

In the context of women entering entrepreneurship through necessity, Tlhoaele believes they are generally fast learners who gain the requisite knowledge quickly in order to succeed. ‘We’re seeing an increasing number of women, particularly those with a corporate background, identify gaps in the market and successfully take advantage of these opportunities,’ he says, adding that ‘a lot can be achieved by actively developing black women entrepreneurs and providing economic opportunities for them’.

Kere concurs. ‘What’s needed is considered and concerted efforts to develop black women entrepreneurs by identifying talent and then developing it through organisational resources and the facilitation of appropriate network development.’ Gender-specific coaching is also critical, she says, as it can help women entrepreneurs thrive through self-awareness, understanding their personal strengths and gaining self-confidence. These soft skills are particularly important in SA’s patriarchal society, where female entrepreneurs need to equip themselves to handle the gender bias and sexism that many men still display in the business environment. Rachelson also mentions confidence and self belief among the biggest challenges for women wanting to start their own business – with other challenges being ‘business acumen and strong commercial skills, such as negotiation skills’ and access to markets.

‘Women at times have limiting beliefs about their own abilities and power to achieve greatness,’ she says. ‘I do not believe women must be like men to get ahead. However, there are aspects that men have mastered in the workplace from which women can certainly learn. Aspects like business is a game; don’t take it personally. And don’t wait until everything is perfect to apply for funding, just say it. It doesn’t have to be 100%.’

There are increasing opportunities specifically for female entrepreneurs in SA – ranging from women-focused social-media networks such as GirlCode and SistaHoodHour, and NPOs such as the Hope Factory, to specialised funding, including the Absa Women Empowerment Finance facility for new and existing women-owned SMEs, as well as long-standing initiatives, among them the government’s Isivande Women’s Fund, Old Mutual’s Masisizane Fund and SAB’s Women-in-Maize.

Some of SA’s business schools provide women-focused entrepreneurial education and support for women in the formal and informal economy, often sponsored by corporates. Johannesburg Business School has been implementing its hands-on Women Entrepreneurship and Leadership for Africa course, while the Entrepreneurship Development Academy (EDA) at the University of Pretoria’s Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) has its roots in a women-centred project – the Goldman Sachs 10 000 Women programme for female entrepreneurs.

‘All our programmes are biased towards women and youth, in line with national development priorities,’ says Sean Smith, GIBS EDA’s senior manager of monitoring, evaluation and research. To date, 56% of the more than 2 700 participants have been female. The academy currently runs a 12-month programme for women farmers in partnership with Corteva Agriscience. The goal is to empower and invest in rural women, enabling them to operate and sustain profitable farms, which will increase productivity, boost economic growth and job creation and eventually help feed a growing population. The EDA is also involved in a programme for women farmers, together with the French embassy and the African Farmers’ Association of South Africa.

‘We’re finding that the recruits understand their agricultural processes – from bee-keeping and livestock to vegetable farming – but don’t have the necessary business acumen to commercialise their enterprises,’ says Smith. The three-month course therefore provides training and coaching in areas such as self- and leadership development, as well as entrepreneurial and managerial competencies.

A programme with the National Home Builders’ Registration Council, meanwhile, focuses on leadership and business skills of female entrepreneurs in the construction sector, where women often struggle to stand their ground in the male-dominated environment.

Many programmes are open to applicants without formal educational qualifications – something that most female SME owners in SA don’t have. Smith points out, however, that even those women who operate ‘survivalist’ micro enterprises in the informal sector, without the formalised benefits of a registered business, may not be as disenfranchised as they are often portrayed. ‘We gleaned data that exposed new ideas around business owners who run spaza shops, small butcheries, early childhood development centres, informal hair salons, car washes and others,’ he says. ‘Most of them don’t see themselves as survivalists or victims of the system, but as plucky, ambitious, resilient and opportunity-identifiers.’

As part of the wider SME ecosystem, they all play a critical role in securing livelihoods and driving the economic recovery. And while it may still be a man’s world, SA’s female entrepreneurs should be supported but never underestimated.