Infrastructure is a bit like health: most people only really start thinking about it when there’s something wrong with it. In other words, when the lack of it causes us personal inconvenience. This doesn’t even have to be as extreme as in Australia, where bushfires closed an outback road and the only other sealed road required a 48-hour detour of more than 4 200 km. After all, infrastructure comes in many shapes – from network infrastructure such as roads, ports, railways, water, telecoms and power generation, to social infrastructure, including clinics, schools and other facilities supporting health, education and basic services.

‘One area of infrastructural need cannot just be decoupled from another immediate one in view of the interdependent linkages in taking investment decisions,’ says Raymond Parsons, eminent economist and professor at North-West University Business School. ‘There is, for example, no purpose in a farmer producing a record crop and then being unable to efficiently and cheaply get it to the market; whether locally or abroad. South Africa needs reliable, economical and smooth flowing corridors linking its various modes of transport for both goods and people.’

Parsons says that while it’s essential to take a holistic and balanced view of the country’s infrastructure investment priorities, the immediate imperative is focusing on bottlenecks, such as electricity and Eskom. ‘Fortunately, “keeping the lights on” is where the maximum space also exists for independent power producers to be liberally accommodated.’

In June, President Cyril Ramaphosa tackled this crippling issue by raising the threshold for self-generated electricity from 1 MW to 100 MW. As a result, the Minerals Council South Africa expects mining firms to ‘rapidly bring to fruition’ a total of at least 1.6 GW of largely renewable, embedded generation. Mediclinic, meanwhile, signed a 12-year power purchase agreement for solar PV with a sustainable infrastructure investment fund manager. This ties in with government’s R1.2 trillion infrastructure programme – a key pillar in the Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan and SA’s version of US President Joe Biden’s $2 trillion ‘build back better’ strategy. ‘Successful infrastructure projects can create a virtuous cycle where infrastructure spend promotes growth and employment creation, which in turn lifts demand and so stimulates further infrastructure investment, feeding the cycle,’ says Annabel Bishop, chief economist at Investec. ‘However, investments need to see returns. In SA, the infrastructure drive is expected to be funded by the private sector while in the US it will be state funded.’

SA’s NDP targets infrastructure investment of 30% (20% from the private sector, 10% from the state) of GDP by 2030. Business Leadership SA (BLSA) noted a sharp fall in such investment: from 20.3% of GDP in 2015 to 17.9% in 2019. In a recent report commissioned from Intellidex, the association said that ‘the fall has been particularly clear in public-sector spending, with both SOE and main-budget spending on infrastructure falling from 7.3% of GDP to 5.4% over the same period’. To reverse this trend, Ramaphosa established the SA Infrastructure Fund, committing R100 billion over the n ext 10 years – which, it is hoped, will leverage R1 trillion in private investments.

‘This fund will blend resources from the fiscus with financing from the private sector and development institutions,’ the president said in his 2021 SONA speech. ‘Its approved project pipeline for 2021 is varied and includes the Student Housing Infrastructure initiative, which aims to provide 300 000 student beds. Another approved project is SA Connect, a programme to roll out broadband to schools, hospitals, police stations and other government facilities.’

The social and economic impact of these projects could be significant. Addressing the backlog in student housing, for example, will allow broader access to higher education and create the technical skills so desperately needed in SA. The majority of institutions in this programme are technical vocational education and training (TVET) colleges and universities of technology, such as Tshwane University of Technology (3 500 new beds), Gert Sibande TVET College in Ermelo (1 500 beds), Majuba TVET College in Newcastle (1 500 beds), King Hintsa TVET College near Butterworth (840 beds), and others. According to National Treasury, R30 million has been allocated to student housing project planning and preparation, with the Infrastructure Fund assisting in structuring, financing and fundraising for Phase 2.

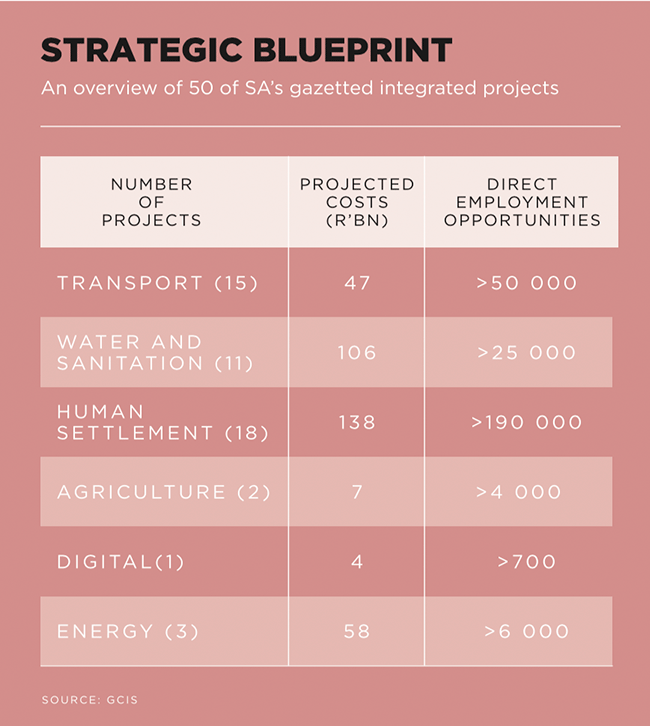

By mid-2021, a total of 62 infrastructure projects had been gazetted as ‘strategically integrated projects’. Many of these had been in planning for years. The gazetted transport projects, valued at a combined R47 billion, intend major upgrades to the N1, N2 and N3 motorways, as well as the development of small harbours nationwide and rail infrastructure in the Northern Cape. In the water and sanitation sector, several projects are ‘investment ready’, notably the Mokolo Crocodile River Water Augmentation Project Phase 2 (in Limpopo), the Lesotho Highlands Water Project Phase 2 (Gauteng); the uMkhomazi Water Project (KwaZulu-Natal); and the Berg River Voëlvlei Augmentation Scheme (Western Cape). The SA Infrastructure Fund sets itself apart through its blended financing model, which lowers the risk for private-sector investors.

‘This model lends itself to innovation and cost-effective structured solutions, as funding is largely secured on a programmatic approach; as opposed to considering individual projects,’ says Mohale Rakgate, who was appointed as Infrastructure Fund group executive by the Development Bank of Southern Africa. ‘The co-financing mechanisms adopted will ensure the achieving of appropriate risk sharing between the public sector and private-sector funders. The Infrastructure Fund will leverage its relationship with Infrastructure South Africa [ISA] to unblock and unlock any policy, regulatory or legislative hurdles in order to speedily bring projects to close.

‘The fund’s objective is to structure, design, package and implement – on an accelerated basis – blended finance solutions for identified infrastructure programmes and projects which require partial government contribution to make them commercially viable through the crowding in of all funding sources, both locally and internationally,’ he says. ‘This includes attracting investment from commercial banks, institutional investors, development finance institutions and multi-lateral development banks. All eligible projects and programmes will be subject to approval by ISA.’

Parsons, who calls the fund ‘promising’, says that its original broad target was to embark on 276 large and small infrastructural projects costing more than R2 trillion, with a project flow that could well see some tangible results by end-2021. ‘Construction companies are already reporting swelling order books,’ he said in early June. ‘It’s clear that in this process, an expansion in the use of public private partnerships [PPPs] will be essential, given the government’s limited finances and budgetary constraints. In South Africa, PPPs constitute only about 2% of infrastructural developments, whereas globally it’s much higher. The obstacles to a greater use of PPPs need to be urgently addressed and overcome.’ Currently there are 34 operational PPPs in SA, including the Gautrain, Chapman’s Peak toll road and SANParks tourism projects, which all attract user charges. The BLSA report highlights the ‘onerous additional bureaucracy’ placed on PPPs.

‘As a result, the use of PPPs has collapsed, with no new projects registered since 2017. This is a central problem that should be addressed through new interventions to support public infrastructure procurement.’

This feeds into the related issue of cost versus quality. ‘We have treated the procurement of professional services in the same way we do ballpoint pens: with the least-cost bidders being awarded projects. The risks, expertise and quality of professional services should always be matched as closely as possible with the cost,’ says Chris Campbell, CEO of Consulting Engineers South Africa (CESA).

‘The Engineering Council of SA, a statutory body, publishes fee guidelines with the minimum rates for certain project types. It is important therefore that we use these correctly and not force companies to discount fees in the downward spiral of least-cost bidders winning.’ He adds that engineering firms need to remain profitable, not least to be able to employ graduate trainees as an investment in SA’s future skills base. In an effort to secure local jobs, stakeholders in the cement and concrete industry have engaged authorities to make it compulsory for government-funded construction projects to use only locally produced cement. According to PPC estimates, cement imports – which rebounded after the easing of lockdown restrictions – accounted for about 8% of demand over the past financial year.

‘It’s vital that our policymakers and regulators appreciate the opportunity that is lost to imports,’ says Njombo Lekula, MD of PPC Southern Africa. ‘The 1 million tons of cement imported to South Africa is the equivalent of a fully integrated cement plant, such as PPC’s De Hoek factory in the Western Cape, which employs about 300 people, running at an estimated value of R900 million in annual operational spend.’ In addition to highly visible brick-and-mortar developments, there is much happening out of sight, where the Infrastructure Fund has revived the SA Connect programme.

‘Strengthening digital infrastructure will offer South Africa the opportunity of establishing a flourishing digital economy, tied in with the opportunity to optimise manufacturing, improve service provisioning and increase employment,’ says Luvuyo Keyise, executive caretaker at the State Information Technology Agency (SITA). ‘To achieve this, however, there needs to be a significant investment in digital infrastructure: from the roll-out of broadband networks to the construction of data centres.’

SITA is accelerating the broadband provision to government stakeholders, so that scalable digital platforms can deliver ‘a great citizen experience’. This strategy entails leveraging existing technology assets and organising these in a modern digital architecture, says Keyise. The current SA Connect targets will further bridge digital gaps by connecting 970 sites in eight rural district municipalities in the Eastern Cape, Free State, KwaZulu-Natal, Mpumalanga, Limpopo, Northern Cape and North West at a minimum speed of 10 Mbps. COVID-19 has highlighted the urgency of bringing such underdeveloped areas online.

‘With the pandemic, we’ve seen a massive shift towards digital technologies for service delivery, business services and consumer services,’ says Vino Govender, chief executive of strategy, mergers and acquisitions and innovation at Dark Fibre Africa, a wholesale, open-access provider of fibre infrastructure. ‘We will continue to densify the network where we already are, and extend the network to areas where there is none. We enable the people who are driving ubiquitous access, to expand on the back of our network, such as the mobile network operators, the 5G operators and data centre operators.

‘We know that it’s not government’s core activity to deliver infrastructure in the telco and ICT space,’ says Govender. ‘Therefore we raise the capital [and]drive and bring the ecosystem partners together. We eliminate the need for infrastructure duplication and see the SA Infrastructure Fund as having the potential to subsidise extension into areas without commercial feasibility.’

And here lies the crux of sustainable infrastructure investment: maximising the social and economic impact of new infrastructure assets in order to create jobs, develop society and nurture SA’s economy back to health.