Not long ago, advertising agencies would have clamoured to win a multimillion-dollar marketing contract with a major global brand. But a crackdown on greenwashing in the US, UK and EU, with stricter laws and the rise of climate activism, is changing this. Ad agencies are increasingly aware of their reputational and legal risks – in addition to the climate risk – associated with taking on clients in industries that have a potentially high environmental impact as well as banks involved in financing fossil-fuel projects.

Greenwashing comes in many guises but essentially refers to misleading the public about a company (or a product, process or investment fund) to make it look more environmentally friendly or socially impactful than it actually is. It doesn’t need to be an outright lie; it can mislead by omission or skilful obscuration.

Recent headlines about multinational Shell’s search for a new media agency indicate just how serious the issue is becoming. The oil giant’s global media account is one of the largest currently up for review (estimated to be worth more than $200 million). According to Adweek, however, no media agencies have publicly admitted to pitching for this work, as this could ‘risk alienating existing clients with strong commitments to sustainability’.

UK and EU regulators have tightened their stance on greenwashing and called out a number of adverts for deceiving consumers about sustainability. Bloomberg lists several adverts banned by the British Advertising Standards Association (ASA) – for example, the popular laundry detergent whose slogan ‘tough on stains, kinder to our planet’ is deemed unclear, because there’s no comparison offered (kinder than what?). Or the almond and soy milk advert claiming to be ‘good for the planet’, which ASA calls ambiguous (in what way is it ‘good’?).

Two major international airlines had their ads banned for misleading customers – one airline said it was ‘protecting the future’ while the other one suggested it was making aviation environmentally sustainable. ASA argues that there are ‘currently no environmental initiatives or commercially viable technologies in the aviation industry’ to substantiate such claims. It also banned an advert by a large UK bank, which highlighted its goal of financing its clients’ transition to net-zero carbon with up to $1 trillion while keeping consumers in the dark about its significant funding of oil and gas projects.

‘Advertising and PR has a crucial role to play in preventing greenwashing in South Africa,’ says Stephen Horn, country director for Clean Creatives SA. More than 600 agencies have signed up globally to this movement, including at least 30 in SA, pledging to decline future advertising contracts with fossil-fuel companies and related trade associations. ‘Our rationale is, there’s no scientific way to make a green case for continued fossil-fuel use. So, inevitably, doing creative work for these companies results in being asked to do greenwashing at some point, which comes with increasing reputational and legal risks,’ says Horn. He expects the global trend of agencies having to cover up or deny they’re pitching on work for fossil fuels to soon arrive in SA. ‘South Africa is behind the curve when it comes to greenwashing regulations,’ he says. ‘But local companies are no doubt looking at the global developments under way and considering how to adjust strategy to minimise risks and also seize the opportunities presented by the transition to clean energy.’

SA currently doesn’t have any regulations speaking directly to greenwashing practices, confirms Merlita Kennedy, a partner at law firm Webber Wentzel. However, the country’s Advertising Regulatory Board and the Consumer Protection Act enable ordinary people to lodge complaints and request investigation when they suspect an advertiser or marketer of greenwashing. Kennedy also expects the stricter laws in the UK, US and EU to have an impact on SA. ‘We will see an increase in greenwashing litigation and regulatory enforcement, with investors and companies making greenwashing activities an enforcement priority for 2023,’ she says. ‘Further, we will see more companies adopting a cautious approach to consumer-facing content to mitigate the risk of greenwashing claims, especially where statements or depictions relate to matters of sustainability, environmental impact and so on.’

In March 2023, the EU proposed draft rules demanding that companies back up ‘green’ claims about their products with scientific evidence – something likely to affect SA companies operating in Europe. According to Reuters, companies wanting to sell goods labelled ‘natural’, ‘climate neutral’ or having ‘recycled content’ in EU territory would have to first carry out a science-based assessment or have the product verified under an environmental labelling scheme. This is meant to help consumers identify which products are genuinely eco-friendly, after the EU Commission found, in a 2020 assessment, that the majority (53%) of ‘green’ product claims only provide ‘vague, misleading or unfounded information’. Under the proposed rules, companies making such claims without scientific proof could be financially penalised.

Similarly, the penalties for greenwashing are likely to rise as the first greenwashing litigation is under way in the US and EU. In May, a California-based passenger filed a consumer class action lawsuit against Delta Air Lines for falsely claiming to be ‘the world’s first carbon-neutral airline’. The 30-year-old complainant told Associated Press about the climate anxiety of her generation and that she felt let down by Delta after learning that the environmental claims (which allow the airline to charge more for flights) could be false. The claims allegedly rely largely on carbon offsets that are only temporary and would have happened even without Delta’s investment.

In June, a Dutch court allowed a civil suit by environmental groups against national carrier KLM to proceed to the next phase. According to Reuters, the target was KLM’s (now discontinued) ‘Fly Responsibly’ campaign, for which the complainants want the airline to apologise to customers.

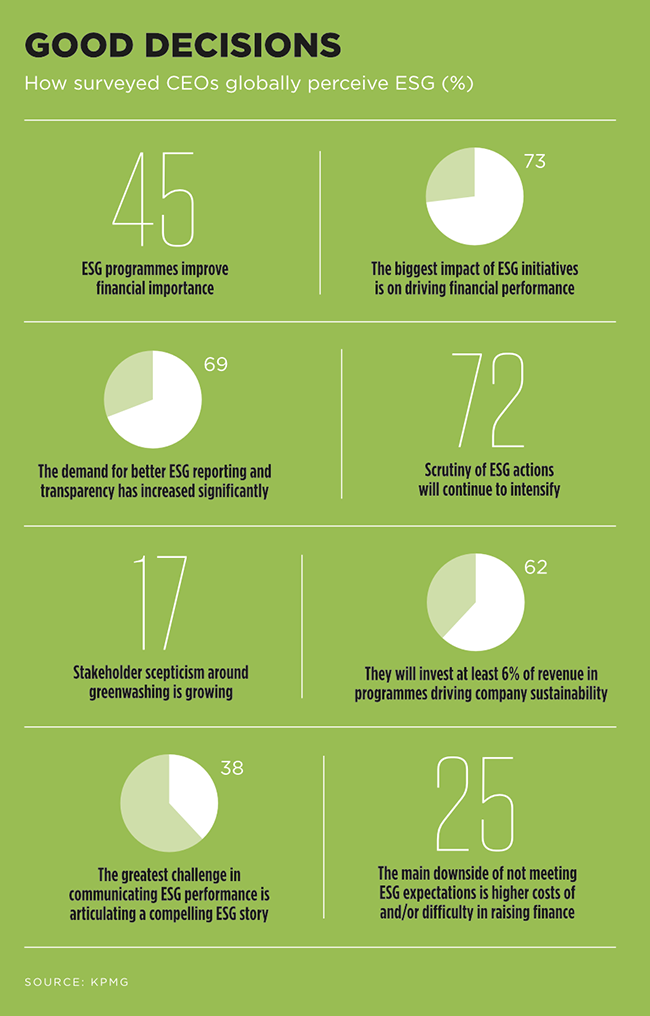

In addition to greenwashing in advertising, there is also increased scrutiny of the financial sector, particularly regarding greenwashing of ESG-related funds and non-financial reporting. Listed companies must, therefore, be aware that misreporting ESG and sustainability information may open them to greenwashing claims, says Webber Wentzel’s Kennedy. ‘South African companies could face civil liability claims before the courts, criminal complaints, or a wide range of other regulatory complaints if their greenwashing is considered, for instance, to amount to a breach of reporting standards, constitute false advertising, violate consumer protection laws, amount to unfair competition or constitute a breach of data privacy laws.’

And the risks don’t end there. ‘It’s possible directors of companies will face personal consequences for failing to act in good faith or in the best interests of the company concerned,’ says Kennedy. ‘And in the age of social media, it is probable that any allegations of greenwashing will receive local – and even international – airtime, also creating reputational risks for the organisation involved.’

The best defence for companies against greenwashing is accuracy and full disclosure. The voluntary JSE Sustainability Disclosure Guidance helps companies identify what information needs to be disclosed – which, in the SA context, means social issues along with the environmental ones, according to Jonathon Hanks, director of sustainability consultancy Incite. He warns of ‘cherry picking’; being selective as to what information you disclose, in order to make yourself look better. ‘Some companies, for instance, don’t want to disclose fatalities and just hide that issue,’ he says. ‘There are a number of companies that aren’t high impact but have quite poor safety records. Simply not disclosing that data, cherry picking it, that’s a kind of greenwashing.’ So that is why fatalities are a core indicator in the JSE guidance and must be disclosed.

Hanks, who was instrumental in developing the JSE Disclosure Guidance, underlines the importance of comparability and consistency. If all companies respond to the core indicators, on the assumption that these are material, it makes it easier to compare their performances because everybody is reporting on the same things. Companies that don’t disclose a core indicator at least need to explain why they can’t or don’t want to disclose the information. Internationally, there is a drive to improve the comparability of data and make sustainability reporting mandatory, which will be helpful in addressing greenwashing, says Hanks.

The shifts to penalise greenwashing, and the requirements to back up green claims with scientific evidence will help consumers distinguish real green claims from fake ones and benefit companies that are genuinely prioritising sustainability, says Horn. It will also be good for SA’s advertising industry. ‘Creativity should flow from a place of honesty. Advertising is not meant to deceive consumers into buying products based on false claims, so tighter regulations will level the playing field and actually allow more – not less – creative freedom, as creatives will feel more secure in what the parameters are.’

By clamping down on greenwashing, consumers will be able to see the world as it is, giving us a better shot at making our future more sustainable.