The sustainability arguments against e-waste have been made and won. The 80 000-odd people who live and work at Ghana’s Agbogbloshie (a notorious global e-waste dumping ground) live with chronic nausea, persistent headaches and wounds that don’t seem to heal. It is said that the air is so toxic that when it rains, you can barely breathe. This isn’t another story about e-waste as an environmental risk or a human health hazard. Instead, it’s about the business case for making sure – whether your organisation is an electronics manufacturer, supplier or end-user – that you know exactly where your electronics go when you throw them out.

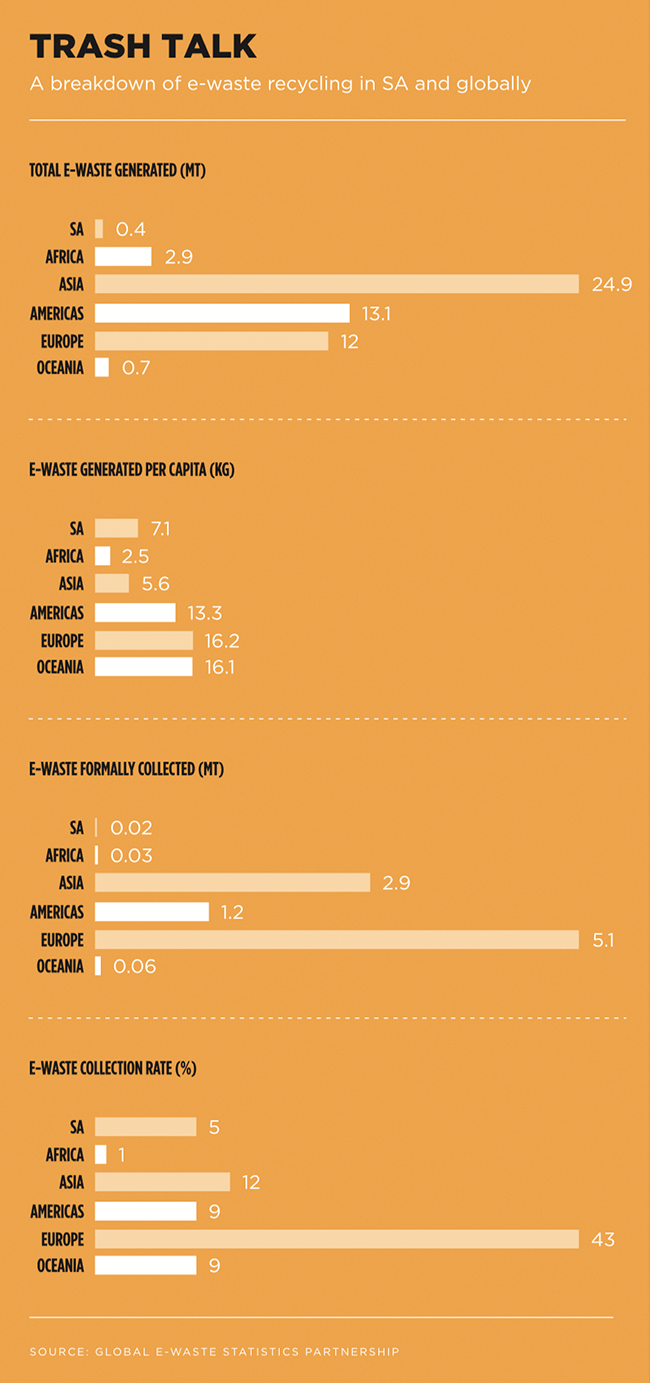

That, of course, means most organisations. And most don’t have a clue where their e-waste goes. Do you? The International Telecommunication Union’s (ITU) new Global E-waste Monitor 2020 report found that the world generated 53.6 million tons (Mt) of e-waste in 2019, at an average of 7.3 kg per capita. However, only 9.3 Mt of that was formally documented, leaving 82.6% of the world’s electronic waste unaccounted for. So where did those old laptops, lamps, computer monitors and mobile phones go?

Where, indeed. The ITU report estimates that somewhere between 7% and 20% is exported as second-hand products or e-waste, but it suggests that ‘the majority of undocumented domestic and commercial e-waste is probably mixed with other waste streams, such as plastic waste and metal waste. This means that easily recyclable fractions might be recycled but often under inferior conditions without de-pollution and without the recovery of all valuable materials’.

As for being exported as second-hand products… Anben Pillay, director of waste policy information management at SA’s Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE), highlighted a significant issue with that during a recent ITU webinar. ‘A variety of electronic equipment comes into the country as second-hand goods, and as donations,’ he said. ‘We’ve had a number of computers coming in from countries outside of Africa in the guise of donations to schools. Once those are received in the country, when you start opening them up to look at the container, if there are 100 computers in there, probably only 10 are fit for use. We deem that to be dumping, and that is a huge challenge for us.’

The e-waste problem – and it really is a problem, as many businesses are about to discover – is only going to get worse. The ITU expects the global total to reach 74.7 Mt by 2030, as more people buy more electronic products with shorter life cycles and fewer options for repair. The impending switch to 5G will only accelerate that further as consumers dump old devices for new ones that are 5G compatible. As John Shegerian, CEO of US-based electronics recycler ERI, recently told Fortune, ‘it’s going to be a bigger turnover of electronics than when we went from analogue to digital, or we went from black and white to colour. And it all has to be responsibly recycled’.

That’s a big ask when there’s no law compelling one to do so. According to the ITU, only 13 African countries had a national e-waste policy, regulation or legislation in place in 2019. ‘The majority of these incorporate the concept of extended producer responsibility (EPR), which is a policy approach growing in popularity globally,’ it states. EPR extends the responsibility of the manufacturers of a product to various parts of its entire life cycle – especially to the product’s take-back, recycling and final disposal.

In a co-written opinion piece, Webber Wentzel attorneys Garyn Rapson, Paula-Ann Novotny and Emma Bleeker point out that in most international jurisdictions, the person who sells the final product (rather than the person who manufactures the packaging) is considered to be the producer for purposes of EPR regulation. This, they write, is because ‘the brand owner is typically the entity that has the power to influence or specify the design of the product’. They also note that, from a consumer point of view, the brand owner is usually associated with the product when it’s littered on the side of the road. ‘[If] you see a Coca-Cola bottle on the floor, you don’t consider that the bottle was made by a bottle manufacturer, not Coke,’ they say.

SA’s newly promulgated EPR regulations came into effect in May 2021, and all existing producers and producer responsibility organisations have until November 2021 to register with the DFFE. ‘As a means through which the manufacturers and importers of products are required to bear a significant degree of responsibility for the impact their products have on the environment, extended producer responsibility ensures that those products are either recycled or upcycled, and that waste products diverted to landfill are kept at a minimum,’ according to the department.

Depending on how carefully one reads the legislation, one might be fooled into thinking that the full weight of EPR lies with the likes of Samsung, Apple, Microsoft, Dell and others. After all, it’s their name on the out-of-style iPhone or the discarded Galaxy; on the worn-out laptop or on the fried desktop. To their immense credit, most tech giants are doing their part. Samsung South Africa, for example, allows consumers to trade in more than 6 000 Samsung and non-Samsung devices.

‘The fact is, all positive changes start with the determination to re-imagine old ways, and to do what’s right for all,’ says Hlubi Shivanda, director of business innovation group and corporate affairs at Samsung South Africa. ‘We’re re-imagining environmental sustainability into everything we do, from packaging to product design, energy consumption to recycling.’

Yet there’s another layer to all of this, which has as much to do with EPR regulations as it has to do with another new law – the Protection of Personal Information Act, or POPIA. ‘Data breaches are a massive problem globally, especially when recyclers are not familiar with legislation or fail to keep up with the latest developments, making themselves liable,’ AST Recycling GM Malcolm Whitehouse told Engineering News in a recent interview. ‘These individuals buy devices and strip them of the valuable fractions, such as printed circuit boards, hard drives and copper cabling, reselling these components to a company that specialises in their recycling. ‘The remaining components are dumped wherever, but they often have an asset tag or serial number that can be traced back to the original owner.’

In terms of POPIA, as a consumer or as a business you are not absolved of responsibility even if you’re certain that you have disposed of the devices correctly (perhaps by donating them to a school). Serious offences carry a maximum penalty of about R10 million, or up to 10 years in prison, or both. In terms of EPR, offenders face similar fines and/or imprisonment. In the situation that Whitehouse sketched out, you might be hit with the double whammy.

So ask yourself again: where, exactly, is your e-waste going?