And you thought it only happened in SA. This year Vietnam spent its hot mid-year months turning off street lights and moving manufacturing shifts to off-peak hours, as the national power system buckled because of an early summer heatwave leading to a surge in demand. Government offices were told to cut their power use by one-tenth. Large factories had to switch off machines as rolling power cuts swept across the country.

Sound familiar? Vietnam’s energy emergency has eerie similarities to SA’s load shedding crisis – and in both cases, it has happened despite a spike in independent energy production and a raft of well-intentioned rebates and subsidies aimed at solving the problem.

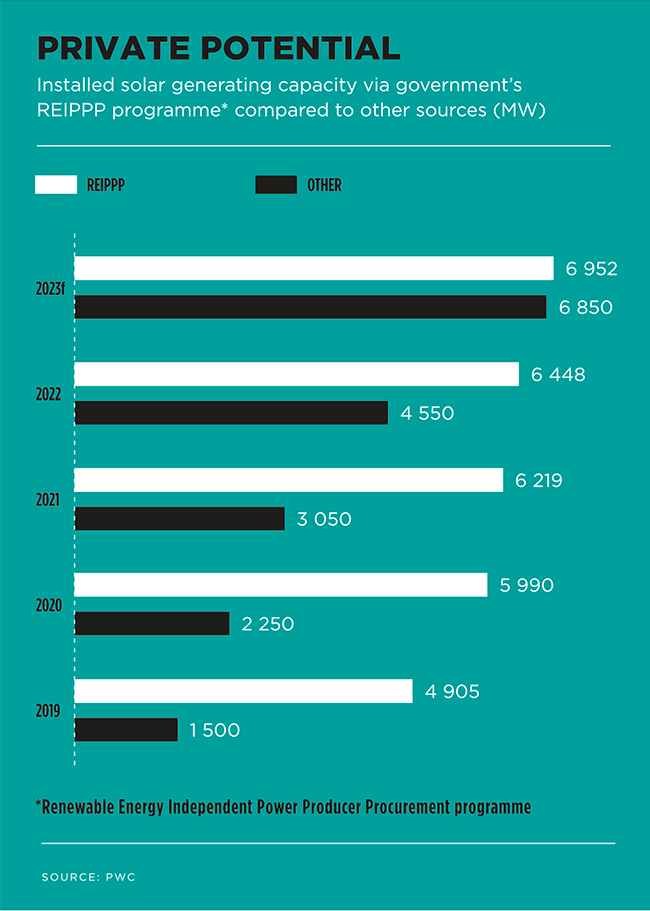

In his February 2023 Budget Speech, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana labelled SA’s lack of reliable electricity supply as ‘the biggest economic constraint’. He pointed to record levels of load shedding (207 days in 2022 compared to 75 in 2021), before announcing two tax measures designed to encourage businesses and individuals to invest in renewable energy and increase electricity generation. ‘From 1 March 2023, businesses will be able to reduce their taxable income by 125% of the cost of an investment in renewables,’ he said. ‘There will be no thresholds on the size of the projects that qualify, and the incentive will be available for two years to stimulate investment in the short term.’

He also introduced a new tax incentive for individuals to instal rooftop solar panels to reduce pressure on the grid and help ease load shedding. ‘Individuals who instal rooftop solar panels from 1 March 2023 will be able to claim a rebate of 25% of the cost of the panels, up to a maximum of R15 000,’ he said. This incentive applies to the 2023/24 tax year only.

‘While these tax breaks are most certainly welcomed, taxpayers are left wanting, for various reasons,’ says Carryn Alexander, partner at law firm Webber Wentzel. For example, a solar energy system requires not only rooftop panels, but also batteries and inverters; however, the solar energy tax incentive is restricted to only the cost of solar panels. ‘Inverters and batteries – which power the inverters – are typically just as, or even more, expensive as the solar panels themselves,’ Alexander points out.

Further scrutiny reveals even more challenges, especially as you start unpacking the language around solar panels needing to be ‘new and unused’. Would panels purchased in February but installed in March 2023 be considered ‘old and unused’? ‘On the face of it, it seems as though this qualifying criterion was inserted to prevent taxpayers from claiming a deduction on solar panels that were acquired prior to 1 March 2023 but only installed on or after 1 March 2023,’ says Alexander. ‘The only clear reason for doing this appears to be cost saving on the part of Treasury.

‘When one considers the magnitude of the energy supply crisis that South Africa is facing, as well as the imminent climate catastrophe, the pecuniary gain that Treasury seeks to obtain is injudicious and defeats the so-called purpose of the solar energy tax incentive.’

Yet at least Treasury offered something. And it’s worth noting that other developing economies have tried similar incentive schemes, with varying degrees of success.

Brazil’s regulatory agency ANEEL has for the past decade encouraged consumers to instal small, 5 MW generation units directly connected to the distribution network. Since April 2012, consumers in the country have been deploying private generation systems, benefiting from a net-metering system. ANEEL claims that by June 2020 there were already more than 245 000 generators such as these across Brazil. While some generate electricity from biogas, biomass or hydro, more than 99% of plants and almost 94% of installed capacity use solar PV generation. As a result, solar now represents an estimated 1.2% of Brazil’s energy mix.

When ANEEL announced it would review the incentive in 2019, it sparked a national debate. Energy distributors claimed that the subsidies that finance the tax exemption for mini- and micro-generators are in effect paid by major energy customers; while the households and small businesses that benefit from the incentives campaigned – with the vocal support of then-president Jair Bolsonaro – under the slogan ‘Don’t Tax the Sun’.

Similar banners have been seen in the US, where the federal government enacted the solar Investment Tax Credit (ITC) in 2006. Consumers who purchase a solar PV system are eligible for a Federal Solar Tax Credit that they can claim on their federal income taxes for a percentage of the cost of the system. In the years since, reports Forbes, ‘the US solar industry has grown by more than 10 000% with an average annual growth of 50% over the last 10 years’. Little wonder; in 2021, the ITC provided a 26% tax credit for systems installed from 2020 to 2022.

The situation in Vietnam is different, yet instructive for SA. In a recent statement Msizi Khoza, head of environmental, social and governance at Absa Corporate and Investment Banking, explained why. ‘In one year, Vietnam’s ambitious rooftop solar installation programme managed to add 9.3 GW of electricity with an aggressive roll-out of 101 000 roof-top solar installations. What makes this even more remarkable is that this was achieved between June 2020 and December 2020 while the world was grappling with COVID-19 lockdowns.’

Like SA, Vietnam is highly dependent on coal energy. Vietnam’s solar success was based on a mass roll-out of rooftop solar which – as Khoza puts it – ‘allowed citizens to not only protect their own access to electricity, but also be rewarded for tackling the broader electricity crisis the country was facing’. The incentive scheme included a feed-in tariff for solar users to sell surplus power back into Vietnam’s national electricity grid at a price guaranteed for 20 years.

And it worked. Vietnam increased its installed electricity capacity tenfold in just two decades, leaping from 5 000 MW in 2000 to 55 000 MW in 2020. By 2023, after opening the market to competition, that capacity was up to 69 000 MW. Yet in the sweltering summer of 2023, street lights were switched off in both Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City while factories faced rolling black-outs. The problem – and here’s the lesson for SA – is that Vietnam now has both an energy surplus and a shortage … depending on where you live. Despite the huge increase in capacity, the national grid is not capable of moving the vast volumes of solar energy generated on the country’s sunny coast to its major cities and industrial hubs.

The parallels with SA are obvious; the scorched Northern Cape could be a goldmine of solar energy, but the electricity would still need to be moved to the country’s commercial centres, hundreds of kilometres away.

There are other, uniquely South African considerations, too – as Imraan Valodia, professor and vice-chancellor of climate, sustainability and inequality at Wits University and director of the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, points out. ‘There is a lot we can learn from other countries, but we need to be careful about two things. Private provision is not necessarily the panacea for all of this. These energy questions need to be linked with broader economic and social goals, including dealing with industrial policy, social policy, inequality and so on,’ he says. ‘We need a carefully regulated system that ensures private provision and social objectives are aligned.’

Valodia believes Treasury’s solar incentives are potentially viable and that they should be encouraged, since SA’s main problem is about energy demand exceeding supply.

‘Any policies to increase supply are a move in the right direction,’ he says. ‘However, there are risks. Energy supply to households via our cities is a big source of cross-subsidisation from rich to poor households, which get basic services at zero cost. As rich households and large firms exit the current supply systems, maintaining this cross-subsidisation becomes a problem.’

Most of all, though, SA’s renewable energy tax incentives need to actually bring about lasting, sustainable change. ‘We need to be careful,’ Valodia warns, perhaps with an eye on wealthy households and big businesses that were already on the path to renewable energy self-generation – not as a solution for load shedding, but as a shift away from Eskom’s coal-powered electricity. ‘We need evidence that the subsidies are effective in changing behaviour, rather than just subsidising things that would have happened anyway.’