Exciting things are coming out of Africa – and they are being increasingly powered by venture capital (VC). Take agritech firm Aerobotics, for example, whose co-founder grew up on a local citrus farm and developed an AI-based drone solution to help farmers protect their tree crops and manage their yield. The Cape Town-based company uses aerial imagery, combined with machine-learning algorithms, to keep an eye on tree inventories and alert the growers to potential pests, diseases, irrigation issues or nutrient deficiencies. In 2021, Aerobotics served farmers and insurance companies in 18 countries worldwide, including the US and in Europe, and raised $17 million in VC funding in a Series B round (more about the funding rounds later).

Fintech start-up Ozow, also from Cape Town, is broadening financial access for the underbanked, specifically those without credit cards. Ozow enables real-time EFT payments using a mobile phone or other smart devices, without the need for a physical card or waiting for the money in the bank account to clear. The company works with major retailers and offers mobile-payment solutions for point of sale, e-commerce, e-billing, peer-to-peer payments and QR codes. In November last year, Ozow’s Series B funding round attracted some $48 million in investment from Tencent, Endeavor Catalyst and Endeavor Harvest Fund.

In yet another Cape Town-based VC success story, DataProphet – the headline-grabbing global AI provider for the manufacturing industry – raised $6 million in Series A funding for further international expansion.

SA’s VC sector has been gaining momentum, despite being not nearly as mature as asset classes such as private equity, according to Tanya van Lill, CEO of the Southern African Venture Capital and Private Equity Association (SAVCA). ‘Traditionally, there weren’t any institutional investors investing in VC funds; all the funding was raised from family offices, high-net-worth individuals and some companies,’ she says. ‘But now we’re seeing a lot of VC money coming from corporates and increasingly also from institutional investors such as development-finance institutions, so there is more capital available to invest in SMEs in South Africa.’

Locally, fund managers are still investing as much as 25% to 50% equity stake in companies, compared to just 2% to 3% in Silicon Valley, says Van Lill, who expects this high exposure to decrease as the SA’s VC industry matures.

‘Venture capitalists are at the coalface of investing in disruptive, innovation-driven start-ups,’ according to Keet van Zyl, co-founder and partner in Knife Capital, the VC company invested in DataProphet, among others. He explains how the COVID crisis has, to some degree, advanced the SA VC ecosystem by accelerating digital disruption globally. ‘Suddenly the perceived high risk of VCs investing in technology ventures as opposed to more traditional business models did not seem like such a big risk any longer,’ he says. ‘But the momentum started swelling long before COVID.’

It all began in the US, where VC money has financed some of the world’s largest firms, including Facebook and Google. The Economist puts the value of US companies seeded by VC at $18 trillion, adding that ‘VC aims to take good ideas and make them bigger and better’.

The way it works is like this – venture capitalists invest risk capital into early-stage, high-growth start-ups in exchange for a stake in the enterprise. As the enterprise grows, it needs more capital and typically raises this through additional financing rounds (called Series A, B, C and even D) where it sells more shares to carefully selected VC investors. This creates opportunities for SMEs and for innovation, which in turn lead to economic growth and positive social impact.

While the VC provides equity funding, skills, experience, networks and shares risks, the start-up exchanges shareholding and autonomy to gain a growth partner. The ‘exit’ is crucially important, as this is where VC deals aspire to reap huge financial rewards for both the investors and the investees.

‘In SA, VC exit is typically a trade sale to a strategic partner, a secondary purchase as part of a larger funding round or a sale back to management,’ says Van Zyl. ‘Unlike the norm in established markets, an initial public offering or listing on the JSE is rare. But with increasing transaction sizes and a maturing market, it is just a matter of time before that channel opens up.’

He explains that, locally, angel investors still make up a significant portion of VC backing but that institutional funders are starting to recognise VC as a viable asset class for investment.

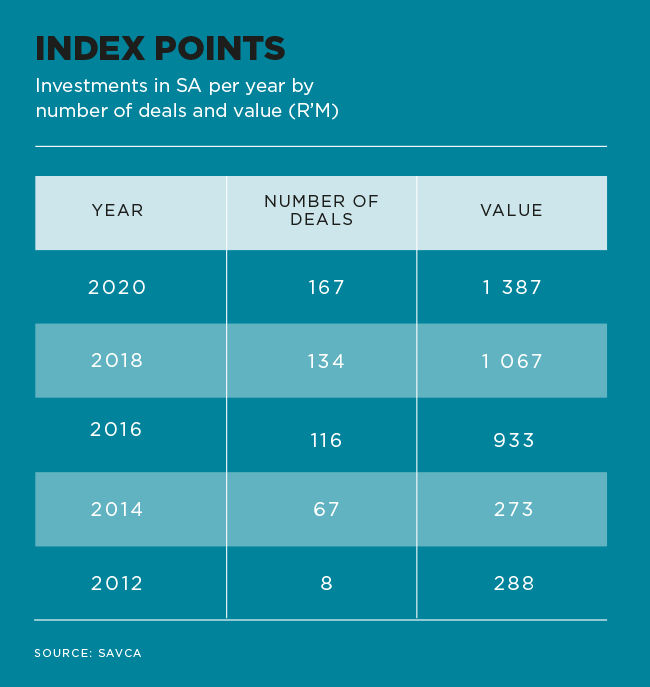

SAVCA’s latest industry survey revealed that the SA VC asset class has experienced eight consecutive years of year-on-year growth in the total amount of capital allocated to early-stage companies. At the end of 2020, this asset class had R6.87 billion invested in 841 active deals.

The public sector remains a major investor, holding R1.75 billion or 28.1% of all active portfolios by value of deals. The majority of VC deals in 2020 involved investee companies that are headquartered in Cape Town (53.1%), with agritech being the largest sector by investment value.

‘In the past, we would have read about one or two new investments per month, and now this has increased to one to two new investments per week,’ says Van Lill. ‘I think this year we’re going to see a record number of investments and funds invested.’

The local VC ecosystem is changing, agrees Aunnie Patton Power, an adjunct faculty member at UCT’s Graduate School of Business and whose recent book, Adventure Finance, deals with this subject. ‘Historically, SA venture capitalists were too risk adverse, unlike other markets where investors were willing to put money behind an idea,’ she says, adding that at the same time, not many companies are suited to the VC model (designed for ‘early-stage, tech-enabled, asset-light, highly scalable companies with a specific type of founder’).

To minimise risk, SA VCs used to require start-ups to first prove their business model before investing in them, as well as protection of intellectual property and other things, according to Patton Power. ‘We’re only now getting to the point of true risk capital, where VCs are willing to invest in proper early-stage, pre-revenue companies.’

She refers to Grindstone Ventures’ new $6.5 million VC fund as an example, which intends to fill the post-seed, pre-Series A funding gap in Africa. The all-female team leading the fund will invest primarily in early-stage innovation-driven tech companies that are also women-led. The team says its ‘secret sauce’ lies in the Grindstone Accelerator, which provides the fund with a pipeline of high-growth businesses and acts as an early due-diligence mechanism that presents de-risked opportunity for returns.

The structured one-year accelerator programme by Knife Capital and Thinkroom Consulting, launched in 2014, has been helping start-ups in Johannesburg and Cape Town to scale up and become more investable and exit-ready.

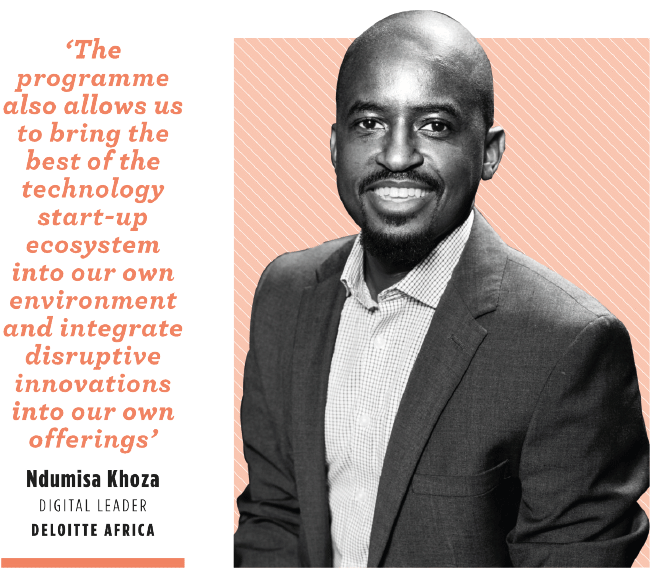

Ndumiso Khoza, digital leader at Deloitte Africa, which is one of the partners in the Grindstone Accelerator programme, says that ‘we partner with disruptive-technology companies to help them become investment-ready and attract the funding that will help them scale their business locally and globally through our Deloitte network. The programme also allows us to bring the best of the technology start-up ecosystem into our own environment and integrate disruptive innovations into our own offerings to help our clients become more innovative and build a competitive advantage in the market’.

He adds that ‘Grindstone contributes to developing home-grown innovations that have the potential to become powerful enablers and catalysts for unlocking new growth momentum in SA’.

Some of the programme’s scale-ups include iKubu (a radar start-up acquired by Garmin); SeaMonster (an augmented reality animation and gaming company that attracted $1 million investment from FirstRand’s Vumela Fund);and PayFast (an online payment gateway acquired by DPO Group).

SAVCA recently received feedback on what attracts international investors to local SMEs. ‘South African entrepreneurs are successful outside of SA because they understand the developing markets as well as the developed ones,’ says Van Lill. ‘Their innovations can be scaled in emerging markets as well as in more developed ones. Their solutions are all tech-enabled and address one of two issues: creating efficiencies or giving access. The latter can grow in any market, although if you think about financial inclusion it’s probably more in the emerging markets, while increased efficiency is what’s attractive to the developed markets.’

There’s still much room to grow the VC ecosystem, and SA needs to improve its support for start-ups and entrepreneurial activity. SAVCA is part of a coalition to push the proposed Start-up Act, calling for government legislation to facilitate the growth and innovation of local entrepreneurs.

‘Many people and organisations have made a conscious effort behind the scenes of demonstrating the benefits of investing in high-growth, high-potential start-ups to advance innovation, job creation and economic growth,’ says Van Zyl. ‘SARS Section 12J – the tax incentive for investing in VC companies – had its issues, but it did bring many retail investors closer to investing into earlier stage ventures, creating awareness and excitement. We are finding that many of those investors are keen to continue investing into this space now that it has been demystified.

‘The catalytic effect of the SA SME Fund over the past few years can also not be under-estimated – seeding many new funds and enabling established players to reach more scale. Institutional funders that backed Knife Capital recently include the SA SME Fund, Skybound Capital, the IFC and Mineworkers Investment Company.’

The involvement of institutional investors in SA VC is a welcome development, but now large companies are being urged to step up their part through corporate venture capital (CVC). Llew Claasen, managing partner at VC firm Newtown Partners, says that ‘CVC enables large established organisations competing on value to undertake disruptive innovation from the outside-in, by creating a safe space to invest in disruptive start-ups that are strategically aligned with the established business over five to 10 years. Over time, a combination of market intelligence and disruptive capabilities are brought into the parent organisation to renew its competitive advantage, without affecting day-to-day operations in the short term’.

Claasen’s VC company partnered with the JSE-listed Imperial group in a $20 million CVC fund focusing on disruptive start-ups in the logistics industry. The fund has already invested in several innovative global start-ups, including digital freight forwarder Shypple, digital pharmaceutical distributor Field Intelligence, point-of-care diagnostics enabler RedBird, and digital freight exchange Lori Systems. Each of these minority investments could become strategically relevant to Imperial in due course, because, as Claasen says, ‘CVC invests into the creation of future capabilities’. And this is something SA desperately needs in order to rebuild the economy and entrench VC as a viable asset class.