The master of business administration (MBA) remains a career accelerator but it’s not fairy dust, according to Martin Butler, programme head at the University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB). Yet, despite not being a magic potion for general consumption, a carefully selected programme can provide future leaders with the tools to make their own magic happen. ‘Those destined for senior and executive management levels will accelerate their careers by 10 to 15 years through an immersive experience that pushes the students to the edge of their capabilities and shows them what they are truly capable off,’ says Butler. ‘It is the personal growth that is probably the least appreciated part of top MBA programmes – exiting as a leader who has worked successfully in diverse teams on complex problems on tight time scales.’

His counterpart at Wits Business School (WBS), academic director Paul Alagidede, calls the MBA ‘the ultimate stress test’ for anyone wanting to succeed in the changing world of work. ‘It provides a rare opportunity to think deeply and critically – not only to absorb knowledge but to actively consider solutions in the face of complex realities. Entrepreneurship, innovation, learning to work with people and individual career development are just some of the powerful ingredients that prepare students to meet global business challenges, both now and in the future.’

However, this most coveted of all business qualifications has lost some of its sparkle. It’s simply not as exclusive as it used to be 20 years ago, because an ever-increasing number of institutions across the globe, some more reputable than others, are adding MBA courses to their offering. As a result, the space is crowded and not all MBAs are created equal. Or in Butler’s words, ‘there are MBAs and MBAs. Lawyers, doctors and engineers are not that often asked where they studied since there is a professional body that maintains a level of quality control. Sadly, many MBAs truly have no external quality scrutiny and simply do not deliver remotely the same experience’.

A benchmark for quality control of business schools is their accreditation – the top three international ones being the US Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business, the UK-based Association of MBAs and the European Foundation for Management Development Quality Improvement System. Only 89 schools in the world have all three. USB is one of the three African institutions with such ‘triple crown’ accreditation, together with UCT’s Graduate School of Business (GSB) and the American University in Cairo.

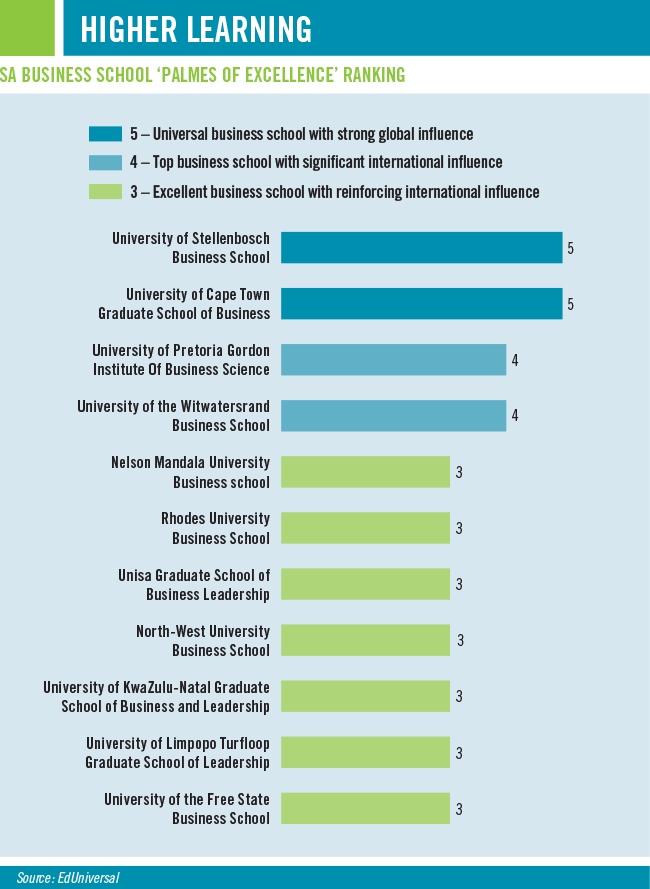

There are also various MBA rankings, compiled, for example, by the Financial Times – in which the GSB, USB and Pretoria University’s Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) regularly feature – as well as those by the Economist, Business Week, Eduniversal and the QS Global MBA Rankings. Butler cautions of the ease with which some rankings are manipulated, but is quick to add that the USB nevertheless attaches value to ‘some of the more credible external parties like QS that [are] often cited by students and reported on in the market’.

Rankings and accreditation can strengthen global credentials, even if they can be onerous and expensive for a business school to obtain, according to Kutlwano Ramaboa, director of international relations at the GSB. ‘Accreditation bodies offer a rounded assessment of schools,’ he says. ‘The three main global assessment bodies assess performance in a holistic way. Their assessment goes beyond just individual increases in salary. They take into account graduates’ contribution to society, value creation and entrepreneurship.’

The Association of African Business Schools launched the first-ever African accreditation in 2018, specifically based on values relative to this continent. Locally, Millard Arnold, CEO of the South African Business Schools Association (SABSA), describes how the association’s 19 member schools have to develop courses that adapt to rapidly changing demands while offering a quality MBA endorsed by the Council on Higher Education.

‘Just getting the [council’s] approval – as you must – can take years. And business schools are doing this, while having to predict the needs of business years from now,’ he writes in an opinion piece in the Financial Mail. ‘Other challenges include more “commoditisation” of management education through “micromasters” designed to address specific needs, understanding artificial intelligence, the future of work, edutourism as a potentially lucrative revenue stream, and creating flexible options for working students.’

Nicola Kley, SABSA chair and dean of GIBS, comments in Business Day that the multi-disciplinary nature of business teaching demands that diversity and complexity be addressed. ‘This is particularly true in the South African and African setting,’ she writes. ‘Even within the teaching of economics, a variety of approaches are being taught, including political economy perspectives.’

According to Owen Skae, director of the Rhodes Business School in Makhanda, high expectations are placed on the MBA qualification because it still is a tough journey. ‘What sets it apart is the opportunity for the MBA student to provide context for the why, how and what they need and want to learn about business, and applying those principles at whatever stage they are in their leadership and management development to get ahead, change direction or start something new,’ he says. ‘The richness of being part of a diverse group of motivated and talented students all bringing different perspectives to thinking about the pressing business problems of the day and conceptualising possible solutions make it an unparalleled experience.’

Diversity and collaboration also play a vital role at the WBS, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2018. ‘Our emphasis on group – syndicate – work means that the study process is conducted in a microcosm of all South African organisations, both private and public sector,’ says Alagidede. ‘Learning by doing is far more superior to mere learning in the classroom. Students have to collaborate when working in small groups in order to pass the courses on our MBA.’

The course includes a compulsory global study tour, where students participate in exchanges programmes at one of the numerous partner schools. Past tours have included Russia, France, China, Dubai, the US, Brazil, Chile and Japan – as well as African destinations such as Botswana, Namibia and Mauritius. This is in line with other SA business schools that strive to equip leaders for globalisation while remaining locally relevant, to be generalists but also have specialist knowledge. To achieve this, some schools are introducing specialisation streams. The GSB, for instance, offers an MBA in social innovation and entrepreneurship; Henley Business School Africa has an MBA in the music and creative industries; while Rhodes has an MBA in sustainable ocean resources, focusing on the blue economy in partnership with the institution’s department of ichthyology and fisheries science.

‘For any business school, being locally relevant and being equipped for globalisation aren’t opposites,’ says Jon Foster-Pedley, dean and director of Henley. ‘Thinking they are is part of the problem and any school that approaches it in that way is propagating a problem too. We have to teach people that globalisation and nationalism aren’t binary opposites but contending polarities that can – and must – coexist. Being equipped for globalisation is fundamentally about being locally relevant too, as all our economies, capital, information, communications and increasingly our people are interconnected, fluid, mobile and thrive through global trade, intelligence and understanding.

‘Of course, at times the balance swings from time to time to extremes – to toxic neocolonisation or to septic hyper-nationalism. What we really need to be teaching executives and entrepreneurs on MBA programmes is to master the arts of advanced thinking, critical thinking, design thinking, systems thinking. Instead of simplistic binary thinking or fanciful magical thinking, we need to develop in them the richness of balanced, multi-perspective thinking, of seeing the extremes, but also understanding the rich middle ground where negotiation, empathy, wise balance and highly-leveraged action lie. It’s an and/both world.’

At USB, the market is being tested for the following new specialisation streams, or ‘focal areas’ in Stellenbosch language: healthcare leadership and management of international organisations. Butler explains that any student can decouple from the generalist stream in their second year of study, to follow the specialisation of their choice, and still cover all the generalist disciplines.

‘These disciplines have a very stream-focused strategic management capstone, and themed international study modules, elective modules and research,’ he says. ‘The market reaction has been very good – specialisation without destroying a key component of value in the MBA, cross-disciplinary complex problem solving.’

And this is where the true value of the MBA lies, in the way it engages students and prepares them for the increasingly complex future of work. This goes well beyond ‘hard’ technical and professional business skills to core leadership competencies that used to be regarded as ‘soft’ (such as creativity, originality, initiative, negotiation, resilience and flexibility) but are becoming crucial for future-proofing one’s career. ‘The WEF Future of Work study indicates that in the next decade these types of skills along with high emotional intelligence, leadership and social influence will be increasingly in demand,’ says Kosheek Sewchurran, acting GSB director.

‘All of the GSB’s programmes focus on developing self-knowledge and self-mastery in our students, as this is a critical starting point for resilience and success in the world of work today. We do this by integrating theory and practice. Our EMBA, for example, was the first in the country to introduce mindfulness practice – a form of stress reduction that used mindfulness techniques including meditation and body awareness – as a core part of the curriculum. Our delegates will tell you that while some of them may have resisted it to start with, they are all grateful for the impact it has had on their ability to self-regulate in high stress environments.

‘Research shows that mindful leaders are less reactive, and more responsive, they adapt more quickly as situations change, and they are more able to regulate their emotions and respond more creatively to challenging situations.’

Some experts say the emerging-market setting of studying for an MBA in SA – a melting pot of inequality, social development and political instability – can give students an edge in an increasingly complex and competitive marketplace. ‘There is no question that industry is changing faster than ever before,’ says Sewchurran. ‘The American military acronym Vuca – volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous – is frequently being used in management and strategy terminology to describe the current global business landscape. Emerging market economies were dealing with Vuca factors long before the term became a global phenomenon. If you can thrive in an emerging market – you can thrive anywhere.

‘The student who has had a full-immersion experience in an emerging context will have an edge. This is because they will have a deeper understanding of the political complexities and instabilities that go hand in hand with these contexts, making them more able to navigate them skilfully, and because they will have gained an ability to work in diverse teams and cultures – making them more adaptive and resilient. These environments require individuals to think on their feet and become comfortable in an environment where uncertainty is the norm.’

For Foster-Pedley, ‘the MBA was started in another age as a movement to educate men returning from war to build businesses to build their countries’ economies. It was an expensive proposition both in time and money, and so became elitist and with its own particular cachet and mystique’, he says.

‘In South Africa I’m less interested in giving a few a competitive edge over others in the job market, but much more invested in providing as many people as possible the skills, knowledge and courage from a progressive MBA that will help them build better business and organisations that will lift and stabilise our economy, bringing a better life to millions. After all, in a developing economy, if a good MBA gives people the essential thinking, skills and character to build better businesses, shouldn’t many people, not just a narrow elite, be able to have the learning and capability that an MBA offers?’

Ultimately, the success of an MBA comes down to how engaged and curious you are, how much effort you put in and whether you have chosen the MBA programme and school that is right for you – no fairy dust required.