The fate of humanity rests on Africa. It’s a big claim, but one that Ivanhoe Mines founder Robert Friedland made emphatically at 2023’s London Indaba. ‘There is no chance of making the energy transition without Africa,’ he said, adding – in his usual attention-grabbing style – that ‘Africa is blessed with the greatest mineral endowment on the planet, and it hasn’t even begun to be scratched – and mining as an enterprise has to be completely, utterly and totally reinvented. What we know as the mining industry has to be thrown out’.

In the months since then, the role of critical minerals has only become more… well… critical. In 2019, the World Bank Group found that production of those minerals – including green minerals such as copper, manganese, cobalt and lithium, as well as rare earth metals – would have to increase by nearly 500% if investment in renewable energy and other green technologies were ramped up to the levels required to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

There’s no universal definition of what makes a ‘critical mineral’. As SA’s Mineral and Petroleum Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe noted at 2023’s African Critical Minerals Summit, each country’s definition varies depending on its country’s needs.

‘Our argument, as South Africa, is that the “critical-ness” of a mineral does not depend on who is using it,’ he said. ‘The fact of the matter is that Africa holds enormous reserves of minerals, such as platinum, manganese, vanadium, nickel, copper, cobalt, lithium, graphite, titanium, rhodium and other rare earth minerals. All these minerals are listed in the various minerals that are deemed “critical”.’

Rare earth minerals are a group of 17 elements whose names sound like Harry Potter spells – lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, promethium, samarium, europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, lutetium, yttrium, scandium – and whose uses range from lasers to electric vehicles, wind turbines, mobile phones and more.

However one defines them, it’s clear that crucial minerals are shaking up the mining industry. As PwC’s SA Mine 2024 report notes, ‘one of the most prominent drivers of M&A activity in the South African mining sector has been the quest for copper and other strategic minerals globally and on the continent’.

PwC highlights the importance of copper in particular, pointing to its robust performance and record-high prices. ‘Copper is a vital component of renewable energy technologies, such as wind turbines, solar panels, electric vehicles, and energy transmission and distribution infrastructure,’ the report notes.

Spencer Eckstein, business development director at mining consultancy Ukwazi, adds that there are, however, some nuances. ‘Global uncertainty and geopolitical factors and their impacts on commodities prices is more likely to impact industry structure and, hence, M&A activity. We expect some consolidation in the PGM sector, which is particularly influenced by the PGM basket prices and mine costs, while coal miners need to diversify into other metals or mineral to balance their portfolios particularly in line with the JET. With copper, so much depends on the demand profile from China and India, and upward momentum in their GDP numbers.’

Copper 360, listed on the AltX and SA’s only pure-play copper mining company, last year announced that it had restarted mining activities at its Rietberg mine after a 41-year pause in copper-related mining in the Northern Cape. In mid-2024, Copper 360 declared that reserves of copper at Rietberg stood at 2.48 million tons with a copper grade of 1.38%.

Copper 360 CEO Jan Nelson noted at the time that the mine study and reserve declaration marks a significant milestone in Copper 360’s capacity. ‘After commencing mining activities recently, now supported by the reserve declaration and report, it again underscores our commitment to mining in the Northern Cape,’ he said. ‘The updated reserve and resource statement better represents our findings and positions the company for a bright future as a copper producer.’

Meanwhile, Rainbow Rare Earths is developing one of SA’s landmark rare earth elements (REEs) projects at Phalaborwa in Limpopo, where it is involved in the first commercial recovery of REEs from phosphogypsum. According to Rainbow’s calculations, the 16-year project will extract 35 million tons of some of the most sought-after REEs, including neodymium and praseodymium, which are used to create strong and durable magnets.

And while many of those minerals are found elsewhere, Africa has the lion’s share. Anybody watching Friedland’s 2023 London Indaba presentation would have recalled his words at the 2022 Investing in Africa Mining Indaba in Cape Town, pointing to the problems with Latin America’s ageing large copper mines. ‘They’re very low grade and they produce a lot of global warming gas,’ he said at the time. ‘They have a lot of work to do to make them green. It’s Africa – where you have a young population – where you have the possibility for introducing sustainable development.’

All of which speaks to Mantashe’s optimistic assessment of the SA mining sector. Speaking at the Mintek@90 Conference in Sandton in November, Mantashe said ‘we can now confidently describe the South African mining industry as a sunrise industry that is diversifying from the gold mining era to a diversified industry with the world’s largest reserves of platinum group metals, manganese, chrome, coal, vanadium and rare earth minerals’.

Mantashe explained that the global transition from high carbon emissions to low carbon emissions has increased the demand for green minerals. ‘As the world’s largest producer of manganese and chrome, the South African manganese and chrome sectors are equally poised to play a significant role in the global automotive and construction industries given the expected demand for green technologies and electric vehicles,’ he said.

Another cause for optimism? China, the world’s top rare earth minerals producer, has also been the biggest importer of the group of minerals since 2019; and in December 2023, in the latest salvo in the ongoing East-West trade war, it banned the export of the technology behind extracting and separating rare earths. There’s a massive demand for these metals and minerals – and SA’s endowment goes far beyond Steenkampskraal, Phalaborwa and the well-known copper mines.

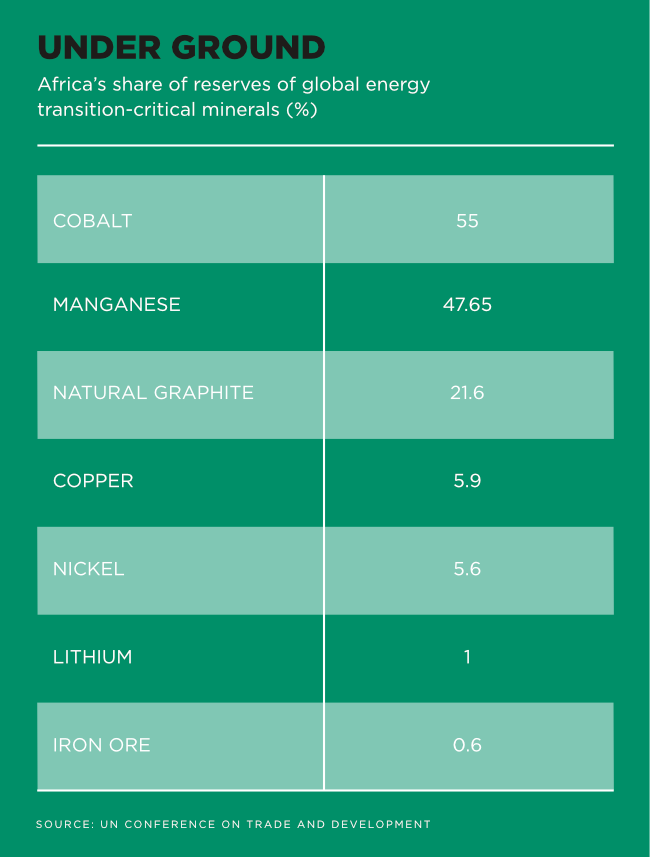

Currently, Africa possesses about 30% of known global critical mineral reserves; but it could hold even more. As the South African Institute of International Affairs points out, Africa is also one of the most underexplored regions, receiving less than 20% of global mineral exploration spending.

That, to Friedland’s point, will have to change. Speaking at an event in Addis Ababa in June 2024, UN Trade and Development secretary-general Rebeca Grynspan outlined the benefits of critical minerals to Africa’s development. ‘Cobalt, manganese, graphite, lithium are not just elements on the periodic table,’ she said. ‘They can be the building blocks of a new era – powering our homes, driving our vehicles, and connecting our world.’

For SA and its mineral-rich regional neighbours, there’s a rare opportunity to shape that future.