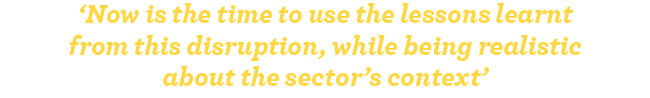

Andreas Kluth, a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, calls it ‘cruel and inhuman’, and ‘an inadvertent socio-economic experiment on young people’. He’s talking about the massive global shift from regular, in-classroom schooling to the strange new world of irregular, learn-from-home schooling during COVID-19. Primary- and secondary-school pupils have borne the brunt of it, with the World Bank claiming that the pandemic had ‘disrupted education in over 150 countries and affected 1.6 billion students’.

‘The education response during the early phase of COVID-19 focused on implementing remote learning modalities as an emergency response,’ the bank notes in a recent report. ‘These were intended to reach all students but were not always successful.’

No kidding. As Kluth puts it, ‘some [countries] resorted to this measure more, others less, and they all did it in different ways. It’s as though they had set out to test what happens in the long term to individuals, societies and nations when you deprive some children of education’.

Yet, as teachers and students across the world have found, while online education is deepening some inequalities, it is breaking others down; and rather than being a temporary, lockdown-enforced stopgap, it’s emerging as a viable, lucrative and fast-growing alternative to the traditional classroom model.

Cathy Li and Farah Lalani of the WEF pointed out in the early months of the pandemic that ‘even before COVID-19, there was already high growth and adoption in education technology, with global edtech investments reaching $18.66 billion in 2019 and the overall market for online education projected to reach $350 billion by 2025. Whether it is language apps, virtual tutoring, video-conferencing tools or online-learning software, there has been a significant surge in usage since COVID-19’.

The authors note that while some believe that the sudden, unplanned shift to online learning (with, as they put it, ‘no training, insufficient bandwidth and little preparation’) will result in a poor user experience that is not conducive to sustained growth, others believe that a new hybrid model of education will emerge. They quoted Tencent’s Wang Tao as saying, ‘I believe that the integration of information technology in education will be further accelerated and that online education will eventually become an integral component of school education’.

Given Tao’s two roles as VP of both Tencent Cloud and Tencent Education – you’d expect him to say that. But what do the students say? And will the growth in educational technology (or edtech) supporting secondary education also bring opportunities in the tertiary-education space?

A recent study by academic publisher Wylie, which surveyed 3 000 online learners in the US, suggests that tertiary-level students are embracing e-learning like never before. While one-third of current prospective students and those enrolled in the 2020/21 school year said they had not considered fully online learning before the pandemic, 61% of the online learners surveyed said they would choose an online programme at another university before enrolling in an on-campus programme.

However, as one digs deeper into the Wylie survey findings, a few oddities emerge. For example, 63% of online students chose a school within 160 km of their location – suggesting that ‘remote’ learning may not be as remote as one might suspect.

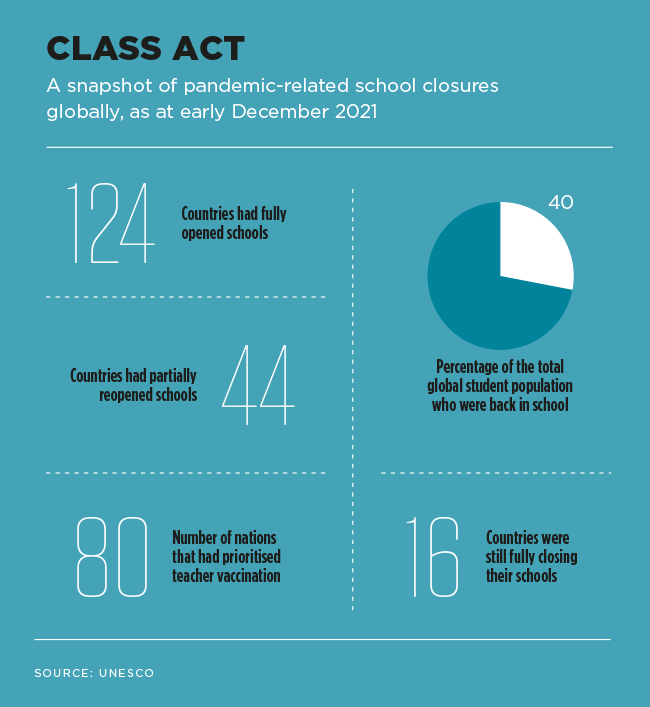

In SA, Unisa has been delivering distance learning to hundreds of thousands of students a year since 1946. (In fact, Unisa is known to attract about one-third of all the country’s higher-education students.) ‘Open distance learning and online learning in higher education are nothing new,’ according to Greig Krull, academic director of digital learning at Wits University’s faculty of commerce, law and management, and Danie de Klerk, head of the university’s teaching and learning centre.

‘Pedagogically sound curricula had been delivered in fully online modes long before 2020,’ they say. ‘But integrating technology into teaching and learning has long been a point of contention in contact universities globally. Part of the reason is the way online tools were sold to higher education institutions, with little consideration to managing the associated changes.’

Krull and De Klerk observe how the shift to ‘emergency remote teaching and learning’ enabled – or perhaps forced – many academics to reconsider their long-held assumptions about in-person teaching and learning. ‘Now is the time to use the lessons learnt from this disruption, while being realistic about the sector’s context,’ they say, adding that one of those lessons involves untangling ‘conflated perceptions of emergency and authentic teaching and learning’.

The point is that while primary school, high school and university students were forced into online education during the national lockdown, that shouldn’t imply that online learning is a last-resort option. UCT recognised that when it launched its new online high school, with classes commencing in January 2022.

UCT Online High School, a collaboration with the Valenture Institute, offers a CAPS-aligned curriculum that enables high school learners in grades 8 to 12 to study at a monthly fee of R2 095. Learning is self-paced and self-disciplined, with one-on-one tutoring and support available whenever students need it. In September 2021 – four months before classes began – the initiative was named among the 12 Top Innovators in the WEF’s WorldClass Education Challenge.

Speaking at the launch in July 2021, UCT chancellor Precious Moloi-Motsepe highlighted how – and hinted at why – the university was extending its expertise into the secondary-schooling market. ‘Using the conventional education model, we can’t build physical schools fast enough to be able to serve Africa’s growing education needs,’ she said. ‘We can’t train and recruit teachers fast enough to meet the estimated 350 000 new teachers required every year to educate the youth bulge on the continent.

‘Even if we could train enough teachers, the best teachers don’t tend to continue living and working in the areas that need them most. [But] what if we can provide an alternative blueprint for scaling quality education on the continent? What if Africa is the continent that countries turn to in the future, to seek inspiration and innovative solutions to hard problems?’

The way Moloi-Motsepe framed it, online education is not a temporary solution to COVID-19’s lockdown schooling problem; rather, it’s an accessible, equitable way of delivering learning to students at all levels.

A handful of SA corporates are also investing in the e-learning space. Telecoms giant MTN recently launched a free online school, working with the Department of Basic Education and the National Education Collaboration Trust to establish an integrated online portal for learners in grades R to 12. The intention is to help close the gap between learners in public schools and those in private schools when it comes to access to learning materials. ‘A full content library will be added to the platform and made available over a period of three years, focusing on key subjects,’ MTN SA CEO Godfrey Motsa said at its launch.

Old Mutual, meanwhile, launched its Africa’s Biggest Digital Classroom initiative, which it subsequently rebranded Learn.Think.Do. According to programme manager Kerrie Taylor, ‘it kicked in 2020 off as part of Old Mutual’s 175th birthday celebrations, but instead of a once-off event, we wanted to create a legacy focused on education’. The programme is hybrid, delivering digital and non-digital financial education through a multi-format, multi-language, multi-platform approach. Its focus is on senior high schoolers, with the intention of rolling it out across Old Mutual’s African territories.

Learn.Think.Do is a free service aimed at promoting greater financial inclusion – and it’s part of Old Mutual’s own growth strategy. ‘It’s in Old Mutual’s interests that people are financially educated, that they make better financial decisions, and that they are more included in the financial development of products,’ says Taylor. ‘That’s only good for Old Mutual’s future.’

Yet online education isn’t only a societal good. As Taylor suggests, corporates can benefit indirectly from its impacts; and – as Go1 recently demonstrated – there’s money to be made in the e-learning industry. In mid-2021 Go1 announced a $200 million Series D funding round, which valued the company at more than $1 billion, and made it – as investors might call it – an online learning unicorn.

About 3.5 million learners and 1 600 customer organisations worldwide use the Go1 platform, and co-founder Melvyn Lubega said the investment would help it expand its edtech product offerings and grow its presence globally. ‘It’s crazy to think how far we’ve come, but our North Star has remained the same, which is that we exist to unlock positive potential in people through a love for learning,’ Lubega said at the time. ‘I think that, ultimately, this validates the size of the problem we’re trying to solve and the size of the opportunity to address that problem.’

While many educators and commentators are focusing on the problem, businesses such as Go1 are seizing the opportunity of providing – and selling – the solution. Global online learning platform Coursera is, too.

Speaking to ITWeb at the release of its 2021 Global Skills Report, Anthony Tattersall, Coursera VP of Europe, Middle East and Africa, said that the company has about 500 000 registered users in SA. About 55% of those users are accessing the online courses via mobile – which, Tattersall said, is ‘very high’ compared to the rest of Africa.

‘It’s interesting to see how much learning is taking place on mobile because the challenges in Africa are often the cost of bandwidth, the availability of a strong WiFi connection, etc,’ he said. ‘We are obviously seeing a lot of mobile usage taking place, which is great.’

It’s also an indication that South Africans have an appetite for learning – and that they will use whatever devices they have to connect to online platforms that provide it.

If, as Bloomberg’s Kluth says, the COVID-19 schooling disruptions really was a test of some kind, then SA’s education sector appears to be passing it.