There’s an epidemic that has spread across all levels of business and government. It doesn’t discriminate. It affects school leavers as well as top executives and politicians. It is called qualifications fraud.

The secretive nature of the epidemic has allowed many of the afflicted to get away with it. Others work in decision-making positions for decades until their deceit is eventually uncovered.

In SA, some high-profile cases include former cabinet minister Pallo Jordan, who pretended to have a degree and doctorate; former KZN police spokesman Vincent Mdunge, who is serving five years in prison for forging the matric certificate that launched his career; and former SABC chairwoman Ellen Tshabalala, who claimed she had a BCom though there was no record of her having achieved it. Meanwhile, legal proceedings are under way against the ex-chief engineer of the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa, Daniel Mthimkhulu. He lied about his academic qualifications and being registered with the Engineering Council of SA – a basic requirement for his position.

Workplace dishonesty and fraud is a huge problem worldwide. On the home front, detected incidents of qualifications fraud have increased by as much as 200% from 2009 to 2014, according to Managed Integrity Evaluation (MIE), a Centurion-based background-screening firm.

In an online media statement, South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA) CEO Joe Samuels said: ‘Qualifications have always been central to successful employability and overall mobility, but also to accessing higher pay levels, benefits and other perks that come with one’s educated, professional status. It’s one of the key reasons why we have seen the growing trend of faking degrees and of PhD fraud among the already employed.’

According to Kirsten Halcrow, CEO of background-checking firm Employers’ Mutual Protection Service: ‘With the increase in online “diploma mills” and access to degrees bought online, the problem is growing.

‘Diploma mills are websites run from remote locations like the Seychelles that sell everything: degrees, masters, doctorates. The biggest problem is detecting them, because sophisticated diploma mills have call centres that are set up to verify the authenticity of the certificates that they sell.’

Approximately 700 such diploma or degree mills have been identified to date, reports MIE. In SA, the occurrence of qualifications fraud is particularly high because of the country’s history of limited access to education, according to KC Makhubele, managing executive of marketing and strategic relationships at Quest Staffing Solutions. ‘I believe that the level of fraudulent representation among the people currently holding high-level positions, from junior management upwards, is higher in South Africa than the international average,’ he says.

‘However, with the doors of tertiary education opening wider and with rising awareness, we’re seeing a slight decrease in such fraud. I believe the new market entrants – the millennials – understand that their academic qualifications are on record and can be verified.’

There are various levels of qualifications fraud. Take for instance CV fraud, where a job seeker submits fictitious, exaggerated or otherwise misleading information. This can range from small inaccuracies in their career timeline, enhancing job titles or embellishing achievements, to a gross misrepresentation of their skills and qualifications.

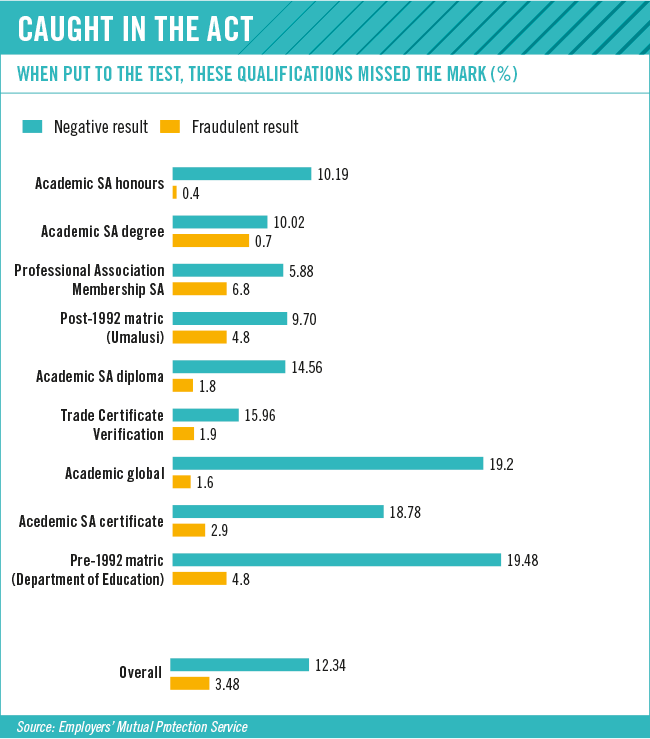

MIE says it’s important to assess the severity of dishonesty: ‘Minor discrepancies include negative results such as a candidate currently in the process of completing their qualification rather than having been awarded their qualification.

‘Major discrepancies on the other hand, include fraudulent results. Examples include a candidate forging or altering their certificate deliberately or never having been awarded the qualification.’

MIE communications head Jennifer Barkhuizen says: ‘Whether you are changing a symbol on your matric certificate or creating a certificate entirely from scratch – you are committing fraud. It’s a criminal offence to alter a document.

‘We urge people not to lie. It’s better to play with open cards – if you haven’t finished your degree, don’t pretend you have. Just tell HR the truth.’

They are bound to find out anyway. The rising awareness of the problem means that more businesses are verifying the qualifications of job candidates and existing staff.

In the fight against bogus credentials, HR practitioners are like medical professionals battling a health epidemic: they are the first line of defence. A rigorous recruitment process will reduce reputational risk to the company, manage costs and improve the quality and retention of the workforce.

Each job candidate should be vetted not just in terms of ability, skills and experience but also honesty, reliability and integrity.

‘My advice is check, check, check. No matter what position, at what level. Never accept a CV at face value,’ says Halcrow. ‘Verify everything, check for criminal records, fraud history, authenticity of all qualifications, check and verify all references.

‘It’s more costly to deal with trying to get rid of a bad hire than to spend the money upfront doing all the checks.’

According to Makhubele, all staff – contracted, permanent or temporary – should be screened as ‘they can make or break your company’. The same applies to entry-level applicants, who may grow from junior into top-level employees.

A company requires the written consent of the individual who is to be screened, in line with the Protection of Personal Information Act.

The vetting process depends on the candidate’s role, job level, category and industry. However, a typical background check and screening could include identity verification (ID, work permit and possible dealings with the CCMA); validating educational qualifications directly with institutions worldwide (matric certificate and tertiary education, short courses and degrees, diplomas and PhD); and a credit check (with major credit bureaus).

It may also include a criminal record check (digital fingerprints and whether a file exists on the SAPS database); a reference check with previous employers (to verify dates, positions, reasons for resigning and character of candidate); and credibility, behavioural and skills testing.

Employers are increasingly also checking their longer-serving staff – especially in the financial sector – as 10 years ago background checks were not as sophisticated.

Makhubele says: ‘The integration of systems has made the process more efficient and faster: you can link into national databases to check on candidates. Prospective employers often use agencies who bring several databases together for them.’

Matric and senior certificate qualifications are, for instance, listed on the Umalusi database – run by the Council for Quality Assurance in General and Further Education and Training, it can only be accessed through agencies. All matric records before 1992 have to be verified at the provincial departments of education.

SAQA runs a verification service for public-sector clients, among others, that checks qualifications against its National Learners’ Records Database. It also verifies foreign educational qualifications and assigns them an SA equivalent.

Furthermore, an African qualifications verification network is also in the pipeline, according to Samuels.

‘Many of the verification challenges experienced in South Africa are mirrored in other African countries, so it makes sense to pool our experiences and skills to create a collaborative, digital hub that services the purposes of countering qualification fraud through education, enhanced security features, digital verification, improved legislation and international partnerships.’

Last year, the government tasked SAQA with developing a national register to crack down on qualification fraudsters. Currently, the Southern African Fraud Prevention Service (SAFPS) hosts a database where private-sector companies list details of fraudulent individuals.

The Shamwari fraud database has around 95 000 entries and is shared by membership organisations that include banks, large retail groups and cellphone companies, says Carol McLoughlin, outgoing SAFPS executive director.

‘One of our categories is employee-related fraud, which includes qualifications fraud such as forged matric certificates or fraudulent employment records. In 2015, we had approximately 1 700 entries in this category.’

Despite the efforts to curb qualification fraud, there are few repercussions. ‘The biggest gap in South Africa is that people don’t follow up and lay a criminal charge,’ says Makhubele.

‘This has a business impact, because a fraudulent candidate is likely to apply at another company. I believe that the employer and the institution that purportedly issued the education certificate should both lay a charge.’

The few high-profile cases that have made it into a criminal court, such as those against the former KZN police spokesman and the disgraced chief rail engineer, may encourage others to lay charges. They also serve to reassure those working towards a legitimate degree.

A zero-tolerance approach towards qualifications fraud could prove to be the remedy against this widespread epidemic.

By Silke Colquhoun

Image: Gallo/GettyImages