When President Cyril Ramaphosa selected his new Cabinet earlier this year, he gave SA women what is rightfully theirs: an equal share. Women now hold 14 of the 28 available ministerial posts. Seeing that half the world’s population is female, this should by now be the international standard rather than something newsworthy. But Ramaphosa attracted global media interest and praise as he announced: ‘For the first time in the history of our country, half of all the ministers are women.’

This makes SA one of only 11 countries in the world (including its fellow African nations Rwanda, Ethiopia and Seychelles) to have achieved gender parity or a female majority in their Cabinets. It’s good news for women – and men – living in SA, as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development explains: ‘Gender diversity in public institutions is particularly crucial, given that these decision-making bodies create the rules that affect people’s rights, behaviours and life choices. Figures show that the increased presence of women Cabinet ministers is associated with a rise in public health spending across many countries.’ Which, according to a Canadian study, is directly linked to a lower national death rate and better overall public health.

This latest milestone demonstrates the progress for women during the 25 years since SA’s first democratic elections in April 1994 – particularly for those who had been cruelly classified as ‘non-white’ and unjustly denied the right to vote, along with being subjected to other human rights breaches during apartheid.

With the arrival of democracy, women were legally guaranteed an equal status to men – for the first time in the country. The progressive new Constitution, introduced in 1996, is explicit. It says in Section 9 (under the heading ‘equality’): ‘The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth.’ The wording is clearly intended to protect women, according to the Constitutional Court, which explains on its website: ‘The grounds “sex”, which is a biological feature, and “gender”, a social artefact, are both included – perhaps unnecessarily. But the result is that this section leaves no doubt that no unfair discrimination based on any feature of being a woman will be tolerated.’

Establishing a modern constitution was very necessary. Prior to this, says the Constitutional Court, SA women were second-class citizens for many years. ‘[They were] under the social and even legal control of their fathers or husbands. Black women were obviously doubly disadvantaged as a result of their race and their gender.’

The online explanation continues: ‘The law, in various forms, has had a significant role in this prejudice. Customary law, for instance, gives black women the status of minors and excludes them from rights regarding children and property. South Africa’s common law deprived white women of guardianship and various economic rights.’

A number of laws have since improved the situation of women. These include the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act of 1996 (which gives women reproductive health rights); the Domestic Violence Act of 1998 (which recognises domestic violence as a punishable crime rather than a private matter and extends its definition to include sexual, economic, emotional and psychological abuse); the Maintenance Act of 1998 (which makes it easier to collect child maintenance, typically from the father); the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act of 1998 (which gives spouses in a customary marriage equal status); the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act of 2000 (which addresses discrimination, harassment and hate speech); and the Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons Act of 2013 (which tackles modern-day slavery and human trafficking in general).

Numerous other laws – including gender-neutral ones such as those legislating child protection, labour practices, immigration and protection from stalking and cybercrime – are continuously improving the situation of women.

Aisha Hamdulay, media and communications officer for the Women’s Legal Centre (WLC), however, believes that while many of our laws are progressive on paper, they ‘fail to achieve substantive equality in their implementation for women. The reform that the law requires is to take a feminist approach to both legislation as well as implementation. It is inherently patriarchal in nature and does not take intersectional differences into account’.

Women are left ‘vulnerable, discriminated against and insufficiently protected’ as a result of laws not being implemented properly, says Hamdulay. ‘This is why we position ourselves as a feminist litigation and law centre.’

Over the past 20 years, the centre has achieved victories related to violence against women, (under the Sexual Offences Act and the Criminal Procedure Act, for example); relationship rights (recognition of Muslim and customary rights); workers’ rights, including sex work and sexual harassment; sexual and reproductive rights, such as access to abortion; and land and tenure rights, for instance, securing tenure for female farmworkers.

Despite all public and private sector investments over the past 25 years to reduce inequality, women – particularly black women – are still severely affected by unemployment, poverty and domestic violence. The office of the Auditor-General of South Africa (AGSA) has raised concerns about increases in femicides and violence against women. ‘Violence against women […] remains a top priority to be addressed in order to enable a safe society where women can thrive,’ it says, underlining the vital role of state organs in advancing equality. The AGSA adds: ‘It is critical for the Department of Women to collaborate with the Commission for Gender Equality, other national departments and relevant role players to ensure that there is continuous improvement in the area of gender equality.’

State-owned entities – such as the Coega Development Corporation (CDC), which is in charge of the Coega special development zone in the Eastern Cape – also drive female empowerment as part of their mandate. The CDC has spearheaded various initiatives for girls and women while internally developing female talent into strategic management positions.

Zola Ngoma, CDC’s head of HR, says: ‘We have embarked on an exclusive and focused women leadership-advancement programme with development and coaching; focusing on a select number of women who occupy senior positions within the organisation. The intention is to advance women towards leadership maturity.’

Meanwhile a 2018 World Bank report on overcoming poverty and inequality in SA reveals the intertwined nature of racial and gender disparity: ‘Race still affects the ability to find a job, as well as the wages. […] Female participants [in the economy] find it harder to find a job, and earn less than men.’ It also finds poverty levels ‘consistently highest’ in female-headed households, whose members are up to 10% more likely to slip into poverty and 2% less likely to escape poverty than members of male-headed households.

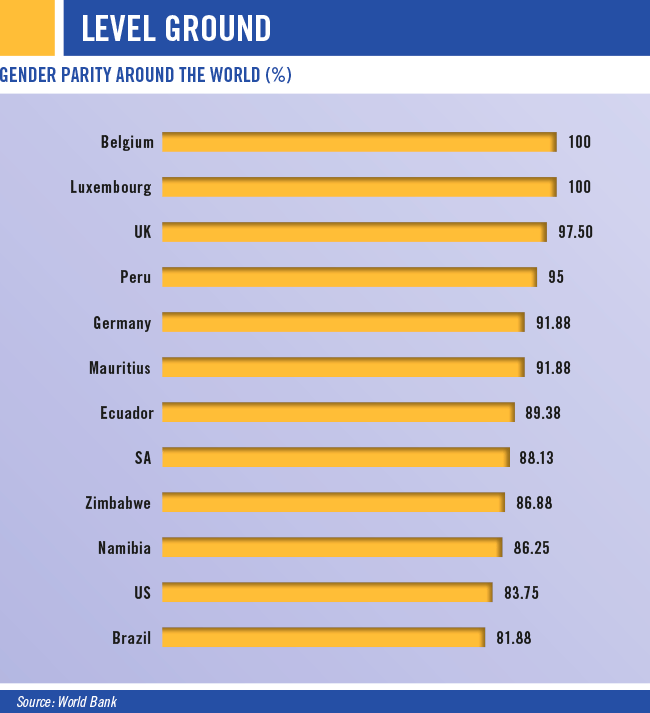

A World Bank study, on the other hand, shows SA women are better off from a legal perspective than some women in industrialised nations. The Women, Business and the Law 2019 report found that only six countries worldwide have equal gender rights, all of them in Europe.

SA’s score (88.13) is well above the sub-Saharan African average (47.37), and higher than the US (83.75) and Switzerland (82.50). This means that SA women have 88.13% of the legal rights of men according to the report’s indicators, which measure women’s interactions with the law at different stages of their careers. One indicator, for instance, deals with ‘having children’ and the report suggests: ‘Policy-makers interested in keeping women from dropping out of the labour force after they have children can look at their economy’s scores in this indicator as a starting point for reform.’

SA recently introduced paternity leave that entitles fathers to 10 days of paid leave after the birth or adoption of their child, financed through the unemployment insurance fund. The NGO Sonke Gender Justice calls this ‘an incredible victory for parents’, saying: ‘Paternity leave is imperative for men, but it is women who will benefit the most from men being offered time off to care for their children.’ After all, women carry most of the burden of being caregivers for their families. A Stats SA survey revealed women do eight times as much domestic and childcare work as men, with the majority of mothers also being breadwinners.

In May, Swedish carmaker Volvo launched its revolutionary gender-neutral parental leave policy in SA, offering six months’ leave with 80% pay, which applies to new mothers, fathers and same-sex parents of biological as well as adopted children. According to Volvo SA, the goal is to improve the work-life balance of parents while reducing career and pay gaps for women.

While this will not directly help the masses of vulnerable, unemployed, destitute or rural women, it’s a vital step towards gender parity. What SA’s women need is an equal share – not only in Cabinet posts and before the law but in all aspects of life, including the economy. Only when a 50:50 balance is achieved will women truly be empowered.