The Krugerrand turned 50 last year. Since 1967, these coins have been the vehicle for selling 53 million ounces of SA gold into the global market, with sales at a cumulative value of some $66 billion at 2017 prices. And the Krugerrand is not only the world’s premier gold coin and a marketing triumph, but also the country’s best example of minerals beneficiation.

Indeed, the Krugerrand is arguably probably SA’s most successful export brand. It offers an internationally standardised investment, with each bullion coin guaranteed to contain exactly 1 oz of 22 carat gold. As a result, its price is pegged to that of the precious metal and it appeals particularly to those who wish to buy gold as a hedge against political and economic uncertainty.

Alan Demby, chairperson of the South African Gold Coin Exchange, points out that bullion coins offer a currency hedge, which may be an important consideration in both SA and the UK at the moment. Its other great virtue, he says, is that unlike stock exchange investments ‘it is not subject to the vagaries of management’.

The Krugerrand also has the great virtue of being easily transportable and tradeable. According to Richard Collocott, head of marketing at Rand Refinery: ‘You can walk into a shop and buy or sell a Krugerrand.’ But although the coin is a favourite with investors who may find themselves having to leave poor, unstable or conflict-ridden countries, Collocott emphasises that it is not legal, in SA, to simply slip a few into one’s pocket and fly to New York. ‘You need SARS approval to legally export a Krugerrand.’

The coin is the result of a partnership between Rand Refinery and the South African Mint, with the latter being a wholly owned subsidiary of the Reserve Bank. It is appropriate to describe the Krugerrand as having been ‘invented’ in 1967 as no similar instrument existed at that time. Today there are of course several rivals, including the American Gold Eagle, Canada’s Gold Maple Leaf, Australia’s Kangaroo, China’s Panda, Britain’s Sovereign (not to be confused with the 15th century coin of the same name) and others.

The Krugerrand, however, remains the premier brand among these offerings and is why, in 2017, it was the world’s top-selling newly minted gold coin, holding more than 32% of the market. However, it has not steadily maintained market share over the decades – the coin was not a popular investment in many countries in the 1970s and 1980s during the sanctions and disinvestment campaign against apartheid.

Its lesser popularity lingered after SA’s democratisation in 1994. After peak sales of 7 million ounces in 1977, the low point was the 10 000 oz sold in 2000. At the time the coin’s future was in doubt. Its saviour was the 2008 global markets crash that saw investors once again looking for a safe haven. In 2017, according to Collocott, Rand Refinery expected to sell 1.4 million oz (39.5 tons) of gold, valued at approximately R24 billion.

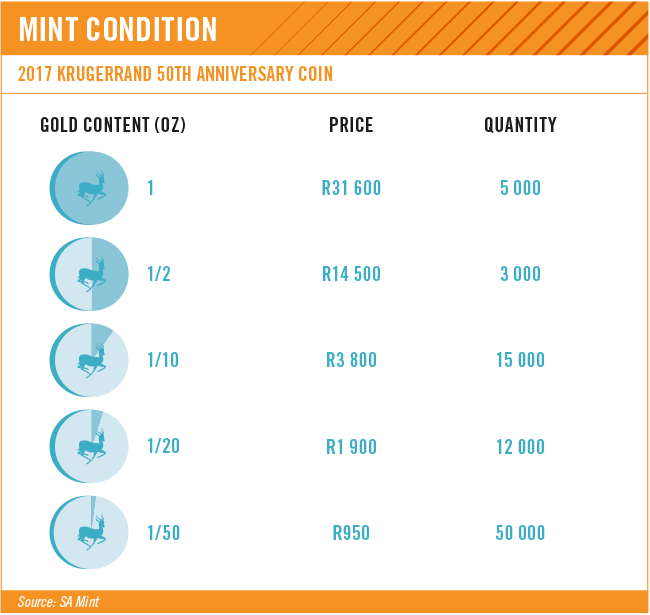

Initially produced as a 1 oz gold coin, smaller denominations were made after 1980. The coin is available in half, quarter and one-tenth ounce varieties. Almost all coins are of the bullion kind with its value determined by the gold price. There are also a number of other ‘proof’ coins released into the collectors’ market where the price is determined by rarity and taste – as is the case with artworks. Collocott says that Rand Refineries releases only about 2 000 proof coins per year (compared to the 1.5 million bullion coins in 2017).

Demby notes that the dealer’s premium (cost of transaction) on the bullion Krugerrand are minimal. ‘It’s also not subject to VAT, although you have to know upfront that it does incur capital gains tax.’ The same is not necessarily true of proof coins. However, Demby says that for those who understand and identify with the urge to collect, proof coins are an especially suitable investment.

‘My advice is to buy proof coins if you want to collect. If you’re simply a speculator – who wants to buy low and sell at a gain as soon as possible – proof coins are not for you. Speculators tend to lose money in the collectables game. To do well, you need to be thinking long term,’ says Demby.

Perhaps more significant than the numbers involved is the fact that the Krugerrand represents the most successful minerals beneficiation initiative in SA’s history. It is often not understood how large a proportion of the country’s gold production goes into these coins. In 2017, Krugerrand production absorbed nearly one-third of the gold mined in SA (estimated to be 130 tons). Only Eskom – which beneficiates coal to produce electricity – can rival the Krugerrand’s claim to have added value to domestic mining production.

Even before the invention of the Krugerrand, Rand Refinery was a good example of minerals beneficiation. The company was established in 1920 to refine crude billion that had previously been shipped to London. In the 98 years since then, it has refined nearly 50 000 tons of gold – about one-third of the total amount ever mined. This raises the issue of what lessons the Krugerrand experience has for a country currently searching for ways to beneficiate its mineral wealth.

‘The first lesson of this history is that the timing has to be right,’ says Collocott, who believes that the Krugerrand was introduced at exactly the right time. ‘There was demand and the product was right. You can’t just decide you want a beneficiation industry and go ahead if these critical factors are not in place. You can take a horse to water – effectively decree something into existence – but you can’t make it drink.’

When the Krugerrand was launched in 1967, gold was about to become much more sought after by private buyers. The following year, the UK was forced to devalue its currency against the dollar. Everyone who had accumulated reserves in sterling – including most Commonwealth governments – lost heavily. Gold became so attractive that India banned private ownership.

Restrictions on the private ownership of gold were nothing new. It was made illegal in the US by the Roosevelt government in 1933 as a part of the armoury it required for the New Deal programme, which faced the task of unwinding the effects of the Great Depression.

Roosevelt was attempting to weaken the dollar – which was pegged against the gold price – in order to stoke the economy. US citizens, with the partial exception of dentists, who were allowed to own 100 oz of gold, were required to sell their private holding to the government at $20.67/oz. In 1934, Roosevelt hiked the gold price to $35, cutting 40% off the value of the dollar. The restrictions were repealed only in 1974 under the presidency of Gerald Ford – marking the end of the gold standard. This was perfect timing for the Krugerrand. The gold price soared and the metal became an attractive speculative investment. More Krugerrands were sold in the three years after the US lifted gold ownership restrictions than at any other time in the coin’s history.

As for beneficiation, ‘it’s all a matter of efficiency’, says Collocott. ‘The question that has to be asked is can you add value to a resource more efficiently than anyone else when all other factors – time, distance, costs – are taken into account. If you can, then you have a good case for beneficiation.’

This view would suggest that other SA attempts to beneficate precious metals and gemstones are unlikely to be as successful as the Krugerrand. It certainly does not mean that jewellery clusters –such as the one at Ekurhuleni on SA’s East Rand – are doomed. But it has to be recognised upfront that they are unlikely to hit the same buttons the Krugerrand benefited from, in terms of timing, efficiency and a growing market.

The East Rand jewellery hub includes the Gold Zone, which is located within Rand Refinery’s main operation in Germiston, as well as the Intsika Skills Beneficiation Project (intended to train previously unemployed black women) and the Ekurhuleni Jewellery Project, which functions as an incubator for young black jewellery manufacturers.

In the meantime, the market for Krugerrands is growing. Collocott says the biggest offshore buyer is Germany, which has responded to uncertainty about the future of the EU – as well as the effective sub-zero returns on German government bonds – by increasing demand for Krugerrands by 13% in the first quarter of 2017. Germany is the gold coin’s biggest offshore market, accounting for 400 000 oz in 2016.

Demby comments that ‘bullion is a funny animal. When there’s movement – in the gold price – people tend to buy, and bullion coins are part of that trend like any other asset class’.

SA remains the Krugerrand’s biggest market, making up 40% to 60% of sales. SA demand has soared in the past two years, ever since the unexpected rotation of finance ministers in late 2015. It remains a hedge against uncertainty and, given current global conditions – the unpredictable Trump presidency, an unstable Middle East, North Korea’s nuclear ambitions, the EU looking fragile and Russia full of new-found assertiveness. Looks like a good bet for the immediate future.