It takes guts to reveal corporate wrongdoings. Life will never be the same for many who speak up to report suspected illegal activities in the public or private sector. In high-profile cases, some whistle-blowers will be celebrated and rewarded for revealing the truth, while others will be ostracised or victimised, and required to pay a high personal price.

Global media headlines reflect some of the risks for those who raise the red flag on corruption: ranging from being fired (‘Care home whistle-blower sacked after raising concerns’), being arrested (‘Swiss banker turned whistle-blower ended up with a prison sentence’), and suffering mental distress (‘ATO whistle-blower facing 161-year prison sentence says he “almost died from the stress”’), to bodily harm and, in extreme cases, being killed (‘Foul play suspected in NGO whistle-blower’s disappearance’; and ‘Vrede dairy farm project whistle-blower found murdered’).

It’s important to understand just what a significant service whistle-blowers provide to the nation and the economy; their disclosures help tackle corruption, fraud, mismanagement and wrong-doings that threaten public health, safety, human rights, the environment and the rule of law. As informants, they are sometimes derogatorily treated as ‘snitches’, ‘spies’ or ‘tell-tales’, but their role is crucial in increasing public and corporate accountability, and improving transparency and corporate governance.

‘When things go wrong in an organisation, the leadership is dependent on those things being highlighted by whistle-blowers,’ says Claudelle von Eck, CEO of the Institute of Internal Auditors South Africa. ‘Without whistle-blowers, the leadership may be totally unaware of the wrongdoing until it’s too late. If our organisations fail, the economy gets affected.’

According to Transparency International (TI), our economy is already affected by corruption, with SA ranking a worrying 73rd out of 180 countries (and ninth in sub-Saharan Africa) in the 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index. In the fight against corruption, TI differentiates between whistle-blowers and external ‘bell-ringers’, explaining that ‘while bell-ringers’ disclosures should also be taken seriously, whistle-blowers’ “insider perspective” means they are particularly well-placed to detect wrongdoing. In fact, insider tips are often instrumental in the detection of corporate fraud and corruption’.

Liezl Groenewald, senior manager for organisational ethics at the Ethics Institute, says: ‘We should ask, what would we have not known if it wasn’t for whistle-blowers? We would not have known about, inter alia, corruption at LeisureNet, SAA, VBS Mutual Bank, Bosasa, Eskom and about state capture, to name a few.’ She says that apart from the moral duty to expose such irregularities, there are legal imperatives as articulated in the Prevention and Combating of Corrupt Activities Act, which makes it obligatory to report financial misconduct of R100 000 or more. ‘The decision to blow the whistle is an immensely private and intrinsically motivated one,’ according to Groenewald. ‘People like Bianca Goodson [Trillian] and Cynthia Stimpel [SAA] spoke up because they believed that it would be in the public interest – perhaps not fully realising that it would cost them dearly, by their own admittance. Typically, whistle-blowers go through an intense thought process and soul-searching before taking the decision.’

The complexities around whistle-blowing arise from the fact that there is no guarantee of how matters will unfold, according to Stephen Sadie, CEO of Chartered Secretaries Southern Africa. ‘A lot depends on the culture of the company,’ he says. ‘On the one side, you may lose your job. On the other side, you may lose your reputation and future career if you sit by and do nothing. Sometimes you may even go to jail if you are an accomplice to fraud.’

He highlights the role of the company secretary as ‘guardian of governance’ within an organisation. ‘Where employees become aware of any unethical or corrupt activities, their first point of call is often to report such incidents to the company secretary. Where the company secretary becomes aware of such behaviour, often at board level, he or she is obliged to report [it] to relevant persons and authorities,’ says Sadie. ‘Failure to report will lead to the company secretary being viewed as an accomplice in such behaviour. ‘South African law does offer protection under the Protected Disclosures Act [PDA, also known as the Whistle-blowing Act], but we have seen company secretaries suspended following a protected disclosure.’

There is legal recourse for whistle-blowers who are being illegally dismissed from their job, demoted, harassed, intimidated, transferred against their will, refused a reference or being adversely affected in their employment opportunities and work security, among other things, according to Steven Powell, head of forensics at law firm ENSafrica. ‘Whistle-blowers who are subjected to “occupational detriment” can be awarded up to two years’ salary,’ he says.

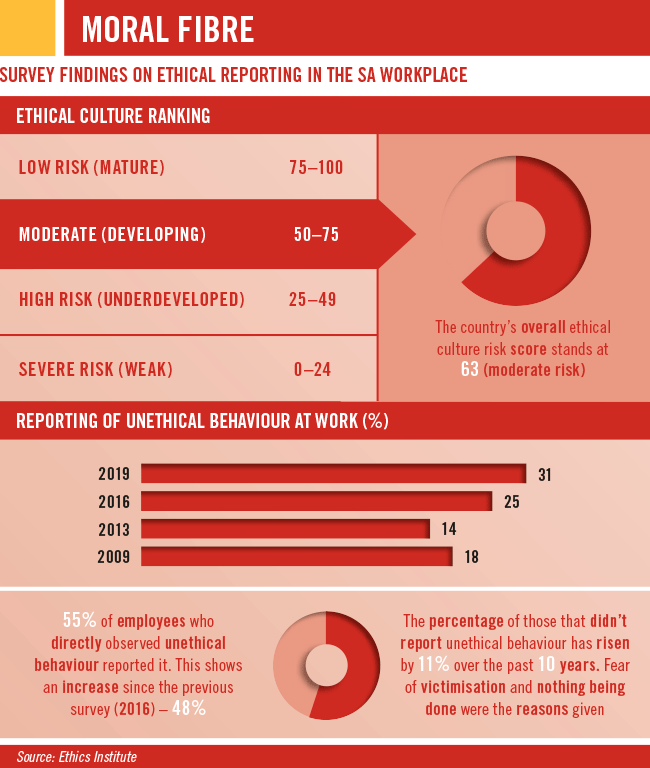

However, Powell explains that while the current legislation, such as the PDA and the Protection From Harassment Act, does provide a measure of protection, this legislation has not typically been very effective. ‘The reality is that most whistle-blowers are discouraged against whistle-blowing as a result of the well-publicised victimisation that happens, not just in South Africa but across the globe,’ he says. ‘The best protection is derived from corporates that have an independent hotline that is able to guarantee they will maintain the confidentiality of the whistle-blower’s identity.’

Companies are legally obliged to establish mechanisms for internal whistle-blowing (‘safe reporting’) that allow employees to report observed wrongdoing to HR, internal audit, the ethics officer or direct line-management, says Groenewald. ‘Anonymous hotlines, which are administered by an independent third-party, also have good systems in place to protect the confidentiality of the information as well as the anonymity of the whistle-blower. The Ethics Institute audits some of these service providers annually against a standard, SafeLine-EX,’ she says. ‘Yet, once they have sent the report to the client organisation, they have no more control over the confidentiality of the information and whether the report will actually be investigated.’

The SA government says its own anonymous anti-corruption hotline has yielded good results, with R420 million recovered at the end of the 2017/18 financial year. The public servants found guilty of misconduct were either dismissed, fined, demoted, given final written warnings or criminally prosecuted. In June this year, Africa’s largest technology services provider, EOH, presented a new, simple-to-use whistle-blowing app called ExposeIT, which is being rolled out throughout the organisation to provide a secure, anonymous and confidential platform for employees. According to EOH, the app allows whistle-blowers to upload and send videos, photos, documents and other evidence to build a strong case. All the information collected will be reviewed by an independent law firm and automatically date stamped.

Stephen van Coller, EOH CEO, told the Daily Maverick Business Against Corruption summit that whistle-blowing platforms require three things in order to be effective: ‘Firstly, the tone needs to be set from the top. [Potential whistle-blowers] need to feel they have agency and independence, and that their voices will be heard. Secondly, once you’ve created an environment in which people know they’ll be listened to, you need to give them a voice. And that’s what prompted the ExposeIT app. We wanted to remove as many obstacles as possible between people with the moral courage to report wrongdoing and their ability to be heard. Finally, whistle-blowers need to be confident that their actions are going to lead to action. If people are given a voice but their words have no effect, people will stop speaking.’

Von Eck adds that organisations wanting to create a ‘speak-up culture’ should celebrate whistle-blowers’ actions by showing that the leadership appreciates them. This could be done, for instance, by putting whistle-blowers first in line for promotions. She also suggests companies should reimburse costs that whistle-blowers may have incurred, such as legal costs, to ‘ensure they’re not out of pocket for doing the right thing’. She points out, however, that she isn’t a supporter of financial rewards or paying whistle-blowers for tip-offs.

Parmi Natesan, CEO of the Institute of Directors in Southern Africa, echoes this sentiment, arguing that whistle-blowers should intrinsically choose to do the right thing, and not be motivated by external monetary gain. ‘Financial compensation could also lead to false allegations being made,’ she says. ‘Organisations’ whistle-blowing policies should cover consequences for false allegations being made by disgruntled employees and the like.’

It’s a criminal offence to report maliciously or in bad faith, with punishment ranging from a fine to a jail sentence of up to two years, according to Groenewald. ‘Organisations in both the public and private sector are legally obliged to have internal whistle-blowing policies, which should include provisions for malicious reporting, so that disciplinary and criminal measures will be instituted,’ she says. ‘However, in the case of anonymous reporters, it’s obviously very difficult to institute such measures/criminal charges and many people do get away with it – often ruining another employee’s reputation.’

Yet most whistle-blowers are attuned to ethical standards and report what they feel is wrong from a sense of obligation to their colleagues, organisation, the public, themselves or society at large, according to the US’ Ethics Resource Centre (ERC). They are motivated by remarkably similar factors, which an ERC report lists as awareness (‘This is wrong, I should do something’); agency (‘Can I make a difference?’); security and investment (‘Should I be the one to say something?’); and support and connectedness (‘Who can I rely on for help?’).

While SA has legislation for the protection of whistle-blowers as well as safe reporting structures in place, these are not sufficient to properly safeguard individuals. In high-profile cases such as state capture, their anonymity is lost, leaving them vulnerable to victimisation. ‘Anonymity makes it difficult to bring charges as you will need witnesses in court who can testify,’ says Sadie. ‘Our law should be amended to provide greater protection for whistle-blowers as there is currently no specific procedure to protect them once they have been identified. Where would we be today without whistle-blowers? The two IT people who came upon the Gupta leaks were motivated by their conscience. Every whistle-blower is a hero.’

There would be less need for such heroism if SA’s leaders led by example, instilling transparent and ethical behaviour from the top down, and encouraged good citizenship and corporate governance. As it stands now, ordinary people have to listen to their conscience and decide to speak up where necessary.

According to Groenewald, some of those who have courageously exposed corruption, at great personal cost, still say they would do it again – simply because it’s the right thing to do.