Since the beginning of the ‘mobile revolution’, around the year 2000, the average human attention span has dropped from 12 seconds to a mere eight. That’s one second less than that of a goldfish.

When Microsoft Corp published these findings in 2015, there was a public outcry about the ill effects of our fast-moving, digitalised lifestyle. Four years later, the general attitude has changed: the dismay about decreasing attention spans has been replaced by discussions about the ‘digital fluency’ of millennials – digital natives who are always online, often on multiple screens simultaneously, and who have developed a highly attuned filter to distil endless amounts of information. This is not a bad thing at all. But it means that brand developers, marketers and HR departments must pay more attention to the needs and wants of a young generation that is growing into the consumers and workforce of tomorrow.

From 2020 onwards, millennials are expected to be the highest-spending generation, thanks to a combination of their own earning power and inherited money. According to the World Bank, the collective annual income of millennials will exceed $4 trillion by 2030. However, lumping together all ‘millennials’ in one single category is far too broad to be useful, says Raymond van Niekerk, brand builder and adjunct professor at UCT’s Graduate School of Business.

Millennials are generally understood to be those born between 1980 and the early 2000s, following what is known as Generation X (born between 1965 and 1976) and the Baby Boomers (1946 to 1964). ‘If you do the maths, millennials are currently aged between 17 and 40 years,’ says Van Niekerk. ‘This is an astonishingly broad spread of people: some of whom are still in school; some are finishing school; some are starting university or are in their first job; others are in their first relationship. Some are having their first child; some have had three already; others are done having children… So to classify all these people as one group makes no sense from a marketing perspective.’

In 2018, Pew Research Centre decided to make 1996 the official cut-off year for the millennial generation. Anybody born after that would fall into the next generation, which is widely referred to as ‘Gen Z’, although Pew notes it is too early to give this cohort a definite name. Segmenting a population group is never easy, because of vastly different interests, experiences, backgrounds and outlook on life.

In 2018, Pew Research Centre decided to make 1996 the official cut-off year for the millennial generation. Anybody born after that would fall into the next generation, which is widely referred to as ‘Gen Z’, although Pew notes it is too early to give this cohort a definite name. Segmenting a population group is never easy, because of vastly different interests, experiences, backgrounds and outlook on life.

This is even more valid in a country as unequal and diverse as SA, says Rachel Thompson, insights director at market research company GfK SA. ‘The pace of technology and social change over the past 20 years, together with the country’s political history, further adds a unique perspective to generational dynamics. And that’s without even considering the different perspectives you might find in a village in KwaZulu-Natal, a suburb in Cape Town and a township in Gauteng.’ In its research, GfK differentiates between millennials (aged 22 to 35, who make up 25% of the South African population) and centennials (aka Gen Z), who are aged 21 and below, and account for 41%.

‘Millennials were entering their teens when cellular technology hit South Africa. They’re a generation of early adopters; who understand the impact of technology on the world and are passionate about incorporating tech into their lives,’ says Thompson. ‘Centennials were born after cellphones were first introduced to South Africa. As the first generation to grow up with mobiles and social media, they achieve a natural balance between real life and the online world.’ She goes on to explain that millennials adopt new technology in order to access cutting-edge features or to improve their health and well-being, whereas centennials are more likely to use tech to save money, make their lives easier and have fun. On the whole, millennials tend to be more status orientated, interested in their appearance and strive for perfection, while centennials embrace themselves and their quirks for what they are, according to Thompson.

Yes, the younger generation also wants power and wealth but uses a more entrepreneurial, fluid approach and is looking for innovative, disruptive shortcuts to the top. ‘There are stories about teens and tweens making hundreds of thousands of dollars a year from online businesses,’ she says. For these younger African millennials – or ‘Afrillennials’ – the boundaries between the digital world and reality have altogether disappeared, according to Ronen Aires, owner of Student Village, an SA youth marketing and graduate development company. In a recent webinar, he explains that these youngsters are image-conscious to the point of being labelled ‘narcissists’, which can be seen in their carefully curated selfie instaposts.

‘They like to spend their money on high-ticket times and on experiences,’ he says. ‘But they don’t have a monogamous relationship with brands. For instance, we found that many Afrillennials use three different cellular brands: one for voice; one for data; and one for their WhatsApp feeds. They don’t go for expensive fashion brands, because to them it’s first and foremost about style, not a big brand name.’ They also find it okay if a product is still in its beta version, as long as it’s being further tweaked and improved to suit their personal needs, says Thompson. ‘Millennial and centennial consumers are knowledgeable and creative, and they love giving their opinion, being involved and co-creating new products.’ She recommends that companies listen and learn. ‘Young customers continuously look for the ability to customise or personalise what they get, so why not involve them in product development? Win them over by using the information they provide to tailor your products and services accordingly.’

One trend that is gaining more traction is the demand for brands with a purpose. ‘Young people tend to favour a cause, because they want to change the system,’ says Van Niekerk. ‘Over the past 15 years they’ve been exposed to austerity and recession in various parts of the social footprint.’ Marketing to this generation should therefore identify with a cause, for instance by addressing an ESG (environmental, social or governance)-related issue that is relevant to the specific target group. ‘It all boils down to really knowing your customer,’ says Van Niekerk. ‘You need to break down your target group to a granular level to truly understand them.’

To illustrate his point, he gives the example of the Nike campaign that featured Colin Kaepernick, the controversial US football player who refused to stand during the national anthem, as a sign of protest against racism and police brutality. ‘Nike was perfectly on the money with this, because the majority of its customers are young, follow sport and have a social conscience,’ he says. ‘In addition, they question authority and don’t like to follow rules; that’s why they had sympathy for Kaepernick’s political statement.

‘As a brand you need to achieve three things: get millennials to trust you; get them to believe in your expertise or in the quality of your products; and get them to like you. For this, you need to create interest or excitement for your product,’ he says. ‘You can’t bore anybody into buying something.’ Brands that are successfully differentiating themselves by tuning into the social conscience of their younger customers include Outsurance, Dove (by Unilever) and Burger King, says Thompson. Outsurance is filling a gap in government service provision by sending ‘pointsmen’ to ease traffic congestion in Johannesburg, Tshwane and Cape Town. Cosmetic brand Dove is promoting positive body image and self-esteem by showing ordinary women in their ads, without airbrushing. Fast-food chain Burger King has positioned itself in its advertising against bullying and for gender equity.

The consensus is that brands have to be authentic and embed their values in every aspect of their operations – not just in their advertising, otherwise young consumers will expose them as fake. ‘Among South African consumers, 46% will select a brand if it supports a cause. Among Generation Z, this rises to 54%, highlighting how this trend will only grow in importance in the years to come,’ according to GfK.

Diamond producer De Beers’ 2018 Diamond Insight Report investigates how to align its industry with the values of younger consumers to ‘create a genuine affinity’ for the ultimate sparkling bling. In early 2018, De Beers introduced the world’s first diamond blockchain (Tracr) to span the entire value chain, digitally tracking each diamond at every stage of its production to prove that it is natural, conflict-free and legitimate. In addition, the group is marketing diamonds in a more liberal way, breaking traditional male-female gender stereotypes. And again, the desire of younger generations for co-creation and personalisation is mentioned. The report quotes a millennial customer who was involved in designing diamond cufflinks as a wedding gift: ‘One had the map co-ordinates for the bench where he proposed in Paris and the other had the co-ordinates of the barn where we would say our vows.’

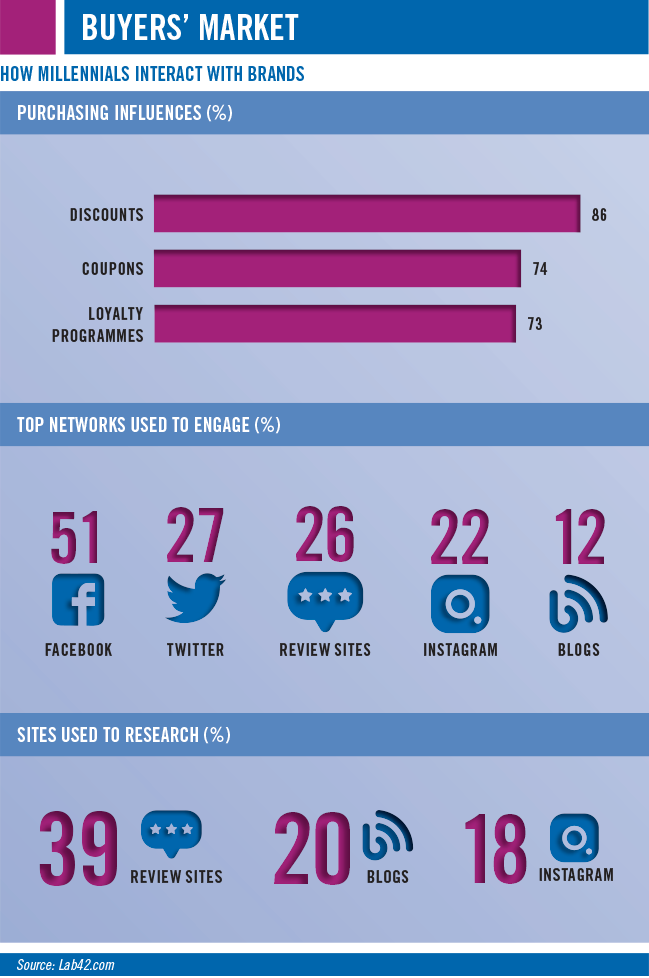

This approach also marks a shift in storytelling, as companies move away from telling their story and towards starting a conversation about their story. ‘The old model of marketing was to “push” information to customers through broadcast channels – television, print advertising, outdoor advertisements and direct mail campaigns,’ says De Beers, explaining how social media, influencers and online reviews now encourage consumers to seek out (“pull”) the brand information they want.

Marketers need to choose the right channels and keep in mind that young people are more visually orientated than their parents and grandparents. ‘They love short-form video, and live on YouTube and Instagram, although Twitter is where you get most of your engagement with them,’ says Aires. It’s essential companies do not discount them as the ‘me, me, me generation’, or as ‘screenagers’ with goldfish-like attention spans, as many businesses missed out by not adapting their HR and marketing strategies quickly enough when millennials first started to enter the job market. Today there are many ways to achieve better insights.

Deloitte, for example, has come up with a ‘millennial advisory board’ – a group of specially recruited young influencers that will advise senior executives in a series of board meetings on any strategic challenge. Another option is to employ millennials and Gen Z in your business – especially in tech, marketing and creative departments, where they could serve as sounding boards. But watch out, there’s already a new generation being born, who will be entirely immersed in a world of AI and robots: generation Alpha.