Thousands of fiddler crabs scuttle away as the zodiac chugs quietly out of the tiny bay, dodging sandbanks as it goes. Just as yesterday, three humpback dolphins offer a flotilla escort out of the harbour. Beyond the natural sand spit, the open sea is as calm as the bay, the reef further out a useful gatekeeper. This is Vamizi Island, in the northern Quirimbas Archipelago and I’m thinking how unlike my previous mainland Mozambique trip it is – no recalcitrant border guards, no string of police roadblocks… Just fly in, a boat trip from Pemba and Bob’s your Indian Ocean uncle – paradise found.

Quirimbas is one of two main archipelagos drawing visitors away from the mainland. Bazaruto further south is widely popular, roughly 35 km off the mainland and served by the increasingly busy gateway of Vilankulo with its bustling airport, charter companies and busy market. The main islands of Bazaruto, Benguerra, Magaruque and Santa Carolina are home to a number of world-class resorts, easily the match of their Caribbean and Pacific island competition. Most have airstrips, or are within easy reach of the mainland, and the regular Johannesburg–Vilankulo air schedule helps with accessibility.

The Quirimbas by contrast are a different world, old-school Indian Ocean – laid back, rare and largely tourist-free. The islands are more remote, though just as accessible from the town of Pemba.

The zodiac gains momentum, planing across the glass top and the dolphins change it up, matching the single Evinrude. We’re headed for the coral reef, the rubber duck loaded with aqualungs and snorkels, the guys back at Vamizi doing all the heavy lifting. I’m here for the hawksbill turtle, if not to watch it come ashore to lay eggs (there’s something uncomfortably voyeuristic about that), then to see it in its natural habitat.

The zodiac pulls up in an apparently random stretch of impossibly blue water, the twin dolphins circle and the complicated business of putting on tanks, mouthpieces and fins ensues. Maybe snorkelling would have been the better bet – this is hard work.

However, the weights and the sticky rubber and the fogged goggles all fade into insignificance as the explosion of bubbles clears to reveal a sunlit playground just metres below the boat. The world slows down, long calm breaths – Darth Vader in Davy Jones’ locker.

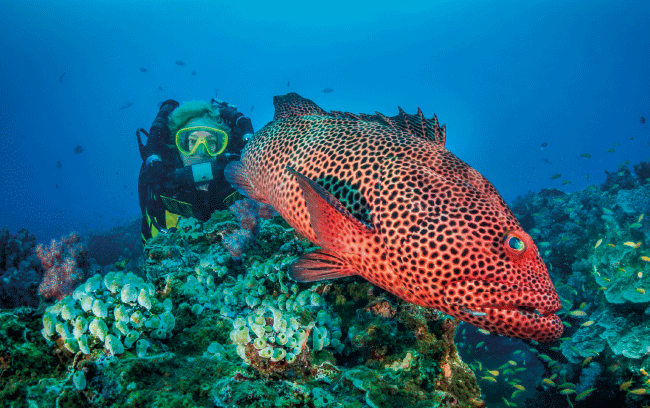

The three of us glide through the kingdom – I’m more fish down here than human, my fellow amphibians trusting me with close-up looks, curiosity the prevailing theme. A monster grouper cruises past, the parrot fish sail, the smaller, brighter fry dart, the royal-blue anemones sway. And 10 minutes in, there it is, my hawksbill, prominent beak a dead giveaway.

It’s entirely unperturbed by my presence, matching my fin kicks with its long flipper strokes. We glide along together, an easy harmony, and I try to imagine how anyone could make spectacle frames out of this elegant creature. They did, though – it was this guy that was most prized for its carapace, as sought after in its day as rhino horn. It’s protected now, but still critically endangered.

Suddenly the hawksbill veers left and the reef community takes fright, an unfelt shock wave suggesting danger. I look up and even our two talisman dolphins have disappeared. My Vamizi dive buddy is pointing beyond the reef, into the turquoise soup. Far away, out to sea a flotilla of dark shapes are closing in. Instinctively I think sharks – too much Jaws as a kid, too many excesses out of Hollywood.

The reality is more remarkable: a large pod of bottlenose dolphins, 30 at least, and before it seems possible they have covered the distance between us and are all around, moving with the kind of lithe grace and purpose that suggests choreography rather than simple locomotion.

An enormous male separates himself from the circling chorus and drifts towards me. He is fully twice my size and in the presence of such intimidating bulk, I forget my dive training 101 – crescent from perpendicular to C-shaped.

Before I can reposition myself, I realise the alpha is copying my orientation. His tail drops, his flippers fold – for a few extraordinary seconds we float there, two Cs, bookends, mirror images, slowly sinking, eye to eye, locked in an inter-species weirdness, probably imagined but never to be forgotten.

Charging elephants, lion kills, a breaching humpback, a Blue whale in Antarctica – nothing will compare to those silent synchronous moments in the Indian Ocean. It’s day two of a two-week trip through the islands, and I’m trying to work out how I will ever top my aquatic eyeballing episode.

The following weeks are a blur of dhows, pink gin, palm umbrellas and the smell of sunscreen and barbecued fish. The whistle-stop tour underlines the difference between the two archipelagos – in the north, it’s all about avoiding people; in the south, it’s a holiday experience, not exactly bustling but peppered with the usual international mix of honeymooners and leathery, jet-set Europeans, avoiding the winter back home at all costs.

In the Quirimbas, besides Vamizi, Ibo Island Lodge, Quilalea Island Resort and Medjumbe are the standout choices. Vamizi is design ground zero as much as island idyll, a coming together of international style, local inspiration and imported quality. Managed by the &Beyond group, it maintains standards that are near impossible to imagine, all the way out there in the Indian Ocean.

The choice accommodation is Tartaruga, a five-bedroomed, open villa with the beach in front and the forest behind. Ibo is on the busiest of the islands (comparatively speaking) and the most idiosyncratic by some margin. Essentially three colonial mansions, the restored properties have been decorated to celebrate their colonial and Arabic history. Rather than villas, there are suites, the best of them arguably Makonde, with a private garden patio and pool. A feature of Ibo is the intricate carved latticework and the huge four-poster beds that reflect the area’s Arabic influence.

Further out in the archipelago is Quilalea Island Resort, owners Chris and Stella Bettany’s private island retreat. The Joburg-based owners of Azura also count Benguerra Island among their portfolio. The lodge is a vintage Indian Ocean retreat, with palm thatch and wood the predominant materials. Of the nine spaces, Villa Quilalea offers the best mix of views, sea, sand and privacy – and there’s a private plunge pool for the fresh-water lovers.

Smaller still is the tiny island of Medjumbe, on which the private lodge of the same name is situated. Twelve chalets manage to squeeze onto the kilometre-long atoll, and service, as you would expect, is individual and comprehensive.

Nearly 2 000 km to the south, the Bazaruto Archipelago is a very different animal and the choice of accommodation is broad, as is the list of activities. Most are water-bound and two should be on every list – one is seeking out the archipelago’s dugong population and the other is a dhow sundowner cruise, both of which are possible from any of the various lodges. The stalwarts that take the lion’s share of the trade are &Beyond Benguerra Island, Bazaruto Lodge, Azura Benguerra Lodge and Indigo Bay, which attract return visitors as much for their location as their charm.

Bazaruto Lodge on the largest island is now managed by Pestana Hotels and Resorts and the 24 A-frame beach chalets are basic but well located and ever popular. Guests are fishing, diving folk, both of which Pestana does extremely well, being Portuguese-based and long-timers in the area. Azura Benguerra Island on the smaller southern island of the same name is an eco-lodge, caters to families and larger groups, and continues Azura’s space-is-king attitude to lodging, with the accent on plenty: plenty of food, plenty to do, plenty of fun. The 18 beach chalets reference the northern Quilalea property in their accent on choice locations and privacy, best placed to catch the prevailing Indian Ocean breezes.

Fun is also the idea at Indigo Bay on Bazaruto, as close to a large international chain resort as Mozambique gets. That means a certain uniformity in accommodation, food and surroundings, but also a degree of anonymity that some prefer on a pass-out holiday. The other benefit of its size is the range of activities – from dune-boarding and kitesurfing to diving and kayaking.

The last is arguably the archipelago’s favourite property, &Beyond’s Benguerra Island lodge, a good balance between resort and retreat, with 12 chalets (open cabanas and walled casinhas) strung out among the palms and sand. Formerly CC Africa, &Beyond is owned by the SA Enthoven family and the Getty Trust, and now has properties across the world.

The holistic idea, shared by Dave Varty and Alan Bernstein and born in Londolozi, was to mix community, land and wildlife in a tripartite approach to tourism. This ethos of mixing sustainable environmentalism with high-end luxury is an approach very much in evidence at Benguerra.

Two weeks and eight lodges later, the Mozambican islands had delivered a simple truth – slow is good. Even at the larger resorts, the essence of the archipelagos is an unhurried serenity, very different to the aspirant mainland, even along the less hectic coastal belt. The few kilometres make all the difference, the famed current taking with it the freneticism of continental life. Shakespeare was right; the isle is full of sounds and sweet airs. No tempest here, just a thousand furlongs of sea. Intoxicating.